Tünde met her American husband in Budapest, Hungary. At his request, they settled in Kecskemét, but eight years ago, they moved with their three children (and Kelley’s mother) to Alaska. Only about 20–30 Hungarians live there on a permanent basis, so there’s no real Hungarian community life there, but rather a few circles of Hungarian friends. Tünde and her Hungarian friends, mostly living in mixed-language marriages, preserve their Hungarian identity through the language, books, and food. She and her husband have always spoken Hungarian at home, so their children master the language without an accent. As a mother, she is already preparing herself for the idea that her future grandchildren will grow up in bilingual families, but she has asked her children never to deprive their kids of learning Hungarian.

***

How and when did you move to Alaska?

I was born and raised in Budapest, and studied as a social pedagogue when I met my husband, who comes from St. George, Utah. Kelley came to Hungary as a missionary of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when he was 18. After two years of service, he went home to finish his degree in economics. But he missed Hungary so much—he longed for lángos and the people he’d grown to love—that when he visited again, he decided to stay. He got a job at ELTE University, where he taught English and computer science. We met in Budapest during a community program. At the time, I was also a member of his church. We were very good friends and eventually, our friendship turned into love. By now, we’ve been married for 22 years. Kelley asked me to move with him to Kecskemét, because he adored that town—he used to say it was the most beautiful city with the kindest people. I had never been there before, but I fell in love with it, too, so we decided to move. Our children—Emma, Benson, and Olivia—were born in Kecskemét. About ten years ago, we began thinking seriously about moving to the U.S. It took Kelley two years to find a job, and since the offer came from Alaska, we ended up moving here eight years ago.

What does your husband do for a living?

In Kecskemét, he worked as an asset manager. While he was applying for jobs in the U.S., he often made it to the final round of interviews, but as a married father living in Europe, he was never the preferred candidate. Eventually, he got a position at the Alaskan branch of the company he had worked for in Hungary. Since moving here, he’s changed jobs twice, the last time just a year ago, and truly loves his current job. Alaska is huge and has countless small aviation companies. Kelley oversees hangars, pilot accommodations, and various types of equipment, including, for example, the machinery that removes ice from airplane wings before takeoff—the aircraft themselves are outside of his responsibility.

What was your main motivation for moving?

After spending more than two decades in Hungary, Kelley longed to reconnect with his own people and see how the U.S. had changed. He was homesick, though he says he now feels at home in both countries, so he’ll probably never be completely content anywhere. Another reason was that we wanted our children to experience their father’s culture, so it would become part of their childhood memories, too, and to take advantage of the opportunities the U.S. might offer them. For example, Benson was an energetic child, but there was no gymnastics club in Kecskemét where he could have trained.

Of course, there were financial reasons, too. We felt we were always working hard but never getting ahead—living paycheck to paycheck, constantly trying to breathe above water. We dreamed of having our own house, even if it meant taking out a mortgage. And finally, there was the spirit of adventure. Between the two of us, I’m the more adventurous, restless soul. It’s not easy, yet incredibly exciting to build a life from scratch somewhere completely different.

Was Alaska a completely new environment for both of you?

Yes. Kelley insists that Alaska isn’t really America—it’s more like Hawaii. Not quite as isolated, but it doesn’t have direct overland connections with the ‘lower 48’ states. The extreme weather also contributes to its sense of isolation. Interestingly, Alaska wasn’t even the most extreme place Kelley was ever asked to work—that was the Marshall Islands…We lived in a kind of waiting state for two years. And when that feeling grows in your heart and soul that something must change, waiting becomes harder and harder. You feel out of place, that you should be somewhere else, but you still don’t know where…

What were you doing in Kecskemét, what did you have to leave behind?

I was blessed with the opportunity to be a stay-at-home mother—not because we were wealthy, but because Kelley could provide enough for our family. What ‘enough’ means differs for everyone; we tried to find the balance: if our child wanted piano lessons, we didn’t want to say no due to financial constraints.

Additionally, in 2012, my nurse friends and I founded the Kecskemét Families Public Benefit Foundation, the Kecsap—which became my great passion, almost like my fourth child. This was the hardest thing to let go of because through it, I felt I had finally found my place in the world and in life, because since I was a little girl, I’ve had a very strong social sensitivity. Through this organization, we helped countless Hungarian families with children in need, whether in the short or long term—illness, accidents, or job loss that threatened their basic survival. We tried to support them, identifying cases where we could extend a hand within our limited resources or connect them with others who could help. We occasionally organized fundraisers, always focused on a specific family or case. Our goal was to tackle clearly defined, visible problems while preserving the dignity of the families involved.

What about your children? How bilingual and bicultural are they?

During his two-year mission in Hungary, Kelley learned to speak Hungarian fluently, and when he returned, he deliberately looked for jobs at Hungarian companies. When we met, I didn’t speak English, so Hungarian became our common language—and it still is, even in Alaska. The Hungarian language is extremely important to me. I never planned on marrying an American, and I probably wouldn’t have if he hadn’t spoken my language. Kelley understands it so well now that he even catches the smallest nuances and gets Hungarian humor. We have to hunt for his mistakes—and when he makes one, we laugh hard but never tell him why, because we don’t want to lose that tiny remaining ‘error margin’…About ten years ago, he also became a Hungarian citizen.

‘I never planned on marrying an American, and I probably wouldn’t have if he hadn’t spoken my language’

In Hungary, my husband tried to speak English with the children and expected them to answer in English. The two older ones became almost bilingual, but the youngest was the most resistant—she understood, but didn’t really want to speak English. For her, the transition was the hardest from a language perspective, but even that only lasted a month or two. The schools here are very well organized for situations like ours—every newcomer is assigned a helper who sits beside them during the first few weeks to provide language support. On her very first day, Olivia even received a Hungarian–English dictionary—which couldn’t have been easy for them to find here!

Since we had never lived in the U.S. before, our children spent their entire childhood in Hungary. Besides their father, there was one more person who represented the U.S. for them: my mother-in-law. My husband came from a small family; his father passed away when Kelley was 12. Later, his mother’s health deteriorated so much that she had to come to Hungary for a corrective surgery—one that had been botched in the U.S. before. Hats off to the Hungarian doctors! After that, she decided to stay in Hungary. At first, she lived with her son, and after our wedding, she moved into a place near us. She was self-sufficient, but needed daily assistance. Later, she came with us to Alaska and lived nearby until she passed away last year. She only knew two Hungarian words—köszönöm (thank you) and macska (cat)—so Grandma was always a constant presence in our lives, and we all spoke English with her. We also used to celebrate American holidays such as Thanksgiving in Hungary, as well as with other mixed American Hungarian families. This way, American culture naturally seeped into our lives, but it’s undeniable that Hungarian culture remained the stronger one, which I don’t mind at all. I openly admit I’m biased, and I always tell my kids that although they come from two cultures, their hearts are Hungarian. Their father says the opposite, but that’s fine—we don’t argue about it. Interestingly, since we moved here, the linguistic rule at home has flipped: now my husband speaks only Hungarian to them.

How did the children feel about the move? Did you have a fixed plan for how long you would stay?

They were at just the right age—no longer little, but not yet teenagers—so they handled the change with relative flexibility. We showed them slide shows and videos about Alaska, and they were very curious. Obviously, saying goodbye to grandparents and little friends wasn’t easy, yet the separation wasn’t difficult. They actually enjoyed the extra attention they received at school because of the move. Olivia’s teacher even organized a farewell celebration. So, they even felt special because of this, and there was no tension. We told them and the family as well that we’d definitely stay for five years. It wouldn’t make sense to move our whole lives across the ocean for any less than that.

Where did you end up in Alaska, and what awaited you there?

People know Anchorage, which is about 45–50 minutes from where we live. Before moving with the whole family, Kelley and I came here for ten days to scout the area and find a home. We met a very good real estate agent, and practically on seeing the first house we walked into, we said: This is it. It’s neither a mansion nor a cabin: just a very charming, modest little family home, which immediately gave us a very good feeling. Later, we realized it’s close to all the schools and conveniently located for the pancake business we had just started. We’ve lived here ever since.

Alaska is 16 times the size of Hungary, yet it has only around 700,000 residents. The distances are huge, the population sparse, and there are no skyscrapers…Our town, Palmer, is a very small town of just a few tens of thousands. There’s no real town square, just a charming main street. It was the first Alaskan–American town founded during the Gold Rush by the first settlers, who originally lived in large tents. Tradition is strong; much reminds you of the pioneer era, and there are historic houses preserved as visitable monuments.

What’s the climate like?

We live in southern Alaska, where there are practically only two seasons: summer and winter, with extremely short springs and falls. The summers are wonderful; the sun barely sets for a few hours. August is a bit rainier, but otherwise pleasantly warm, with the temperature never exceeding 23°C (73°F). On some days, it can feel much hotter, which I was told is due to the angle of the sun. So, it can feel very warm sometimes, but for those three to four months, the weather is beautiful. People are so happy to be out of winter that they fish, hike, and camp endlessly. Summers are extremely active, with many tourists.

The winter lasts for 8–9 months, and there’s a period when we hardly see the sun: it only appears for a few hours before setting again. One can get used to this, but I always warn others: come here only if you have strong relationships. A couple should move to Alaska only if their bond is loving and secure, because here they’ll be very locked in together. Those who love winter sports can find a mountainside and a hotel for skiing and other winter activities; it’s harder for those who don’t. We ourselves are not big winter sports enthusiasts.

Temperatures can be extreme. It can reach -25/-30°C (-13/-22°F), though not for the entire winter; otherwise, we certainly wouldn’t live here. Usually, it’s between 0 and -10°C (32 to 14°F). In the north of Alaska, though, like in Bethel, winters are brutal; I don’t know how anyone can live there…You are either born there or paid enormous amounts of money to work, for example, as a teacher for a year. That’s why salaries in Alaska are relatively good, yet life is very expensive. We’ve experienced beautiful snowfalls of several meters. Last winter was very mild; people who have lived here 60 years say it has never been this mild, with so little snow. Two years ago, however, we had to dig paths through the snowdrifts to reach our own shed or garage. Snowplows came constantly, and if one got stuck, another came to free it. You learn to live with this.

What are Alaskan people like?

How should I put it? I think they are a bit closer to the Hungarian spirit than the sometimes superficially friendly Americans of the ‘lower 48’: more reserved, self-contained, yet extremely helpful. For example, the very day we moved into our house in the summer, Mick, our single neighbor in his 60s, walked over. He knocked, introduced himself, and said: ‘If there’s a problem, come to me; if not, the next time you’ll see me is when the first big snow falls. After I clear my driveway, I’ll come over and clear yours.’ And indeed, we next saw him in November, completely snowed in, when he was already shoveling our driveway at five in the morning. In between, we never socialized—he showed no interest in that—yet he’s a great neighbor, because he always shows up when help is needed. The kids brought him some homemade cookies a few times; he simply made a funny comment upon receipt and closed the door…Later, he wrote to say they were delicious. We only hear from him a few times a year—when he clears snow or warns us about moose in the yard. Moose are wonderful, but very dangerous; you mustn’t startle them, as they can charge and crush you. I always told the kids: Never run outside. Bears don’t come near us, but toward the end of winter, moose gradually come closer to human settlements in search of food. The nature and wildlife here are absolutely amazing…

Are all Alaskans so reserved? Don’t you feel lonely?

No—but for me, Mick is the perfect neighbor. Of course, we’ve made friendships here too; if we really want, we have people to spend time with. But honestly, my friends from Hungary are still the most important to me. I have two friends here I can always rely on, and I have Hungarian friends in Alaska for whom I’d go through fire. But alongside them, it’s essential for me to nurture my friendships from Hungary. I try to pay attention to them throughout the year, and whenever I visit Hungary, I meet up with them. These are the kind of friendships where even if we haven’t spoken for six months, we just pick up where we left off, even if the online conversation takes a bit longer.

‘For me, family and friends are enough’

For me, family and friends are enough. As much as I’m a social person, I also enjoy being alone, so Alaska isn’t difficult in that regard. Some people live completely isolated here, practically in cabins in the wilderness; we, however, live in communities and houses. That was important to me—if something happened with the children, I could run to a neighbor or friend for help…But even when I’m alone, I’m perfectly happy with my books, dogs, nature, the internet, and my own thoughts.

So, are there no Hungarian communities in Alaska?

I don’t think there are—at most, there are Hungarian friendships…Most members of our Alaskan online group of 70–80 don’t even live here; many have only visited for a few days or weeks, asked for some advice, and then never left the group, so that number doesn’t reflect the real Hungarian population. It’s hard to know exactly how many Hungarians live in Alaska. If I had to guess, the permanent Hungarian population is no more than 20–30. Allegedly, most live in Fairbanks; there used to be quite a few 15 years ago, but I don’t know the current numbers, and I don’t know any of them, as it’s an eight-hour drive from us. In Anchorage, there are about eight Hungarians; in Palmer, we’ve only heard of one besides us, but we still don’t know who…Besides my Hungarian friends, I recently met two Hungarian men who’ve been living here for years. Most of the others are women with American husbands. So, it’s mostly mixed-language families living in Alaska, too few and too far apart to form a community.

How do you maintain your own and your children’s Hungarian identity?

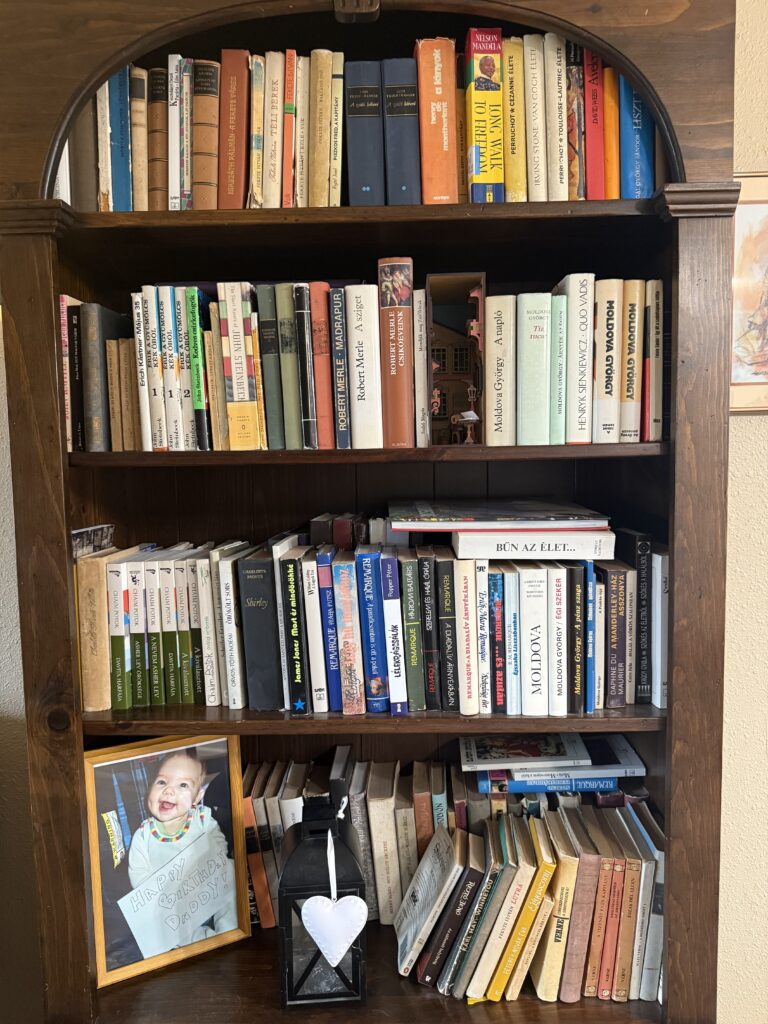

Hungarian language and books are my main connection to Hungarian culture here—including Hungarian humor, which I think is completely unique. Before we left Hungary, I asked my friends if they wanted to give me a farewell gift; they should pick a ‘love book’ from their shelf, write a little farewell message inside, and send it to me. My goal was to create a small Hungarian library at home—it’s still quite modest, currently of about 500 titles. Even today, I sometimes pick up a book and read friends’ messages they wrote back then.

I’ve been taking my children to the library since they were very young, especially Emma, who’s still a bookworm today. The other two aren’t quite as avid, but I made sure they know: if they want to read classic world literature, I can hand it to them in Hungarian. This past summer, Olivia visited Hungary, so I sent a list of books to my father to get and send back to us with her.

I also exchange books with my Hungarian friends in Alaska. My library is a bit monotonous, as my heart belongs to early 20th-century literature, especially Russian classics, which few want to read in 2025…But I’ve been requesting contemporary works from Hungary as well. When Noémi Orvos-Tóth’s books were published, they circulated among us. Now I’m trying to get hold of works by Krasznahorkai from home—I’m a bit behind with him…

How do you stay connected with your Hungarian friends in Alaska?

I’ve found fantastic friends here—amazing Hungarian women. Évi is from Transylvania (Romania), Klári from Felvidék (Slovakia), and Regi from Sárospatak, Hungary. Regi met her American soldier husband in Hungary while working as a translator at the Taszár airbase back in the day; she’s an Iron Woman, constantly hiking, climbing, and skiing. Our larger group is about seven or eight women. We try to meet at least quarterly, and every six months with our families as well—for a picnic or dinner. When the children were small, we celebrated St. Nicholas (Mikulás) together; now we have Christmas gatherings where we draw names and exchange gifts. We also have second-generation Hungarian friends like Ildikó, whose parents came to America decades ago. She was born here and speaks Hungarian well. We sometimes switch to English for her, but we usually speak Hungarian.

Regi, Évi, and I often do summer trips together—fishing trips with a camper, just the three of us women, catching, filleting, and eating what we catch. During our meetups, there’s always Hungarian food: Klári makes amazing goulash from fresh moose meat, there are layered potatoes, meatballs in tomato sauce, crepes (palacsinta), and sourdough bread (lángos). I also cook Hungarian dishes at home. Salmon has entered our menu, especially in good summers. Sometimes I make hamburgers, but in a Hungarian style…

You recently started a crepe ‘drive-thru’. What’s the story behind it?

Olivia wanted to ride horses, which isn’t easy here: you need a covered arena and an experienced trainer. It’s also very expensive: two lessons a week cost about $600 per month. As I mentioned, Alaska is pricey, just slightly cheaper than Hawaii. Benson competes in sports, traveling extensively, and Emma is now studying psychology at a university in Texas—so the financial pressure is huge. I had to come up with a solution. I started by making pancakes once, with a donation-based system. Neighbors were incredibly generous—one paid nearly a month’s riding lesson fee, and in total, it covered two and a half months’ worth. I was deeply moved. Similarly, when Emma left for Texas, a friend left $200 in an envelope for her—just slipped it through the door…It showed me that human kindness and helping young people aren’t determined by nationality.

Afterwards, people started asking: ‘When are you making pancakes again?’…At the time, I had just finished a work project and had no job besides family. Renting a commercial space is extremely expensive, and I didn’t want a mobile food-truck setup either. Our property is near a well-used road, while trees shield us from the traffic, so I thought: Why not create a ‘drive-thru’ at our house? A friend built a small U-shaped driveway in our backyard, and now I open it two—soon three—times a week. September was my first full month, and I earned Olivia’s riding fees—a huge relief. Americans love European-style pancakes; it’s something special for them. When they persistently asked for a savory version, I made ‘Hortobágyi’, which they loved so much that they started to pre-order it. Some even learned to pronounce its name!

‘My goal isn’t wealth, just to provide some financial flexibility to be able to support our kids’ passions or hobbies’

My goal isn’t wealth, just to provide some financial flexibility to be able to support our kids’ passions or hobbies. Besides that, I love cooking and chatting with people—especially without traveling or letting them into my house. This way I’m also sharing Hungarian culture: my ‘drive-thru’ is called Budapest Crepe and has a sign displayed about Budapest and famous Hungarians.

Finally, how do you see your family’s Hungarian identity in the future?

Our children are now truly bilingual and have both Hungarian and American identities. All three speak Hungarian fluently without an accent, and their Hungarian familial ties remain strong. They keep in touch with our relatives since I keep reminding them to call, send updates, and photos. We send them home individually due to the high cost of travel. Olivia spent six weeks in Hungary this summer. She was very excited and said Hungarian youth are much more thoughtful than Americans. It took her only a day or two to get used to Hungarian vocabulary, especially related to riding. However, we are aware that their future partners might not be Hungarian. Whatever happens, I’ll always speak Hungarian to my children and grandchildren—that’s certain. So will my husband. I constantly remind them that speaking two languages and understanding two cultures is a true gift. I also keep telling them: if you want your kids to understand their grandmother, you’ll have to make the effort. I’d be terribly ashamed if my children didn’t understand their grandparents—that’s why reading in Hungarian was once mandatory in our home. Everyday conversational vocabulary is very limited compared to literary language; to preserve culture, one must read. I wasn’t always popular because of that, but I didn’t care. As for their family, I think, if there is a dedicated ‘Hungarian time’, for example, during dinners, it’s a good start. Finally, when all our children have left home, we may move to the ‘lower 48’ states, and then Hungary will be considered when we retire.

Read more Diaspora interviews: