This is an abridged version of the original interview published on 777blog on 13 August 2023.

Kovács György—known to everyone simply as Gyuri—is the director of Sík Sándor Scout Park in Fillmore, New York, the most significant international Hungarian scouting camp in North America. He is also the scoutmaster of the Bessenyei György Scout Troop No. 22 in Cleveland, Ohio. His lifelong friendships with adult scouts—who support the park both physically and financially—also extend to helping Cleveland’s youth scout troops and organizing Scout Day. A conversation about fleeing, American adventures, building a new life, and the greatest passion: scouting.

***

How did you end up in America?

At the end of 1972, we fled to Italy with my mother and sister. The year before, we had already attempted to escape through Yugoslavia, but we were caught at the border. At the Yugoslav–Italian border, we ran through a minefield, with heavy gunfire aimed at us. My sister was detained by the Italians, my mother was beaten by the Yugoslavs, and a Yugoslav border guard held a gun to my ear just for his own amusement. I was 12 years old, and Marika was 15. The Hungarian border guards, on the other hand, were decent—they didn’t report us, they just put us on a bus back to Vecsés, Hungary. Despite this, the next year, my mother somehow secured vacation permits and passports to Italy. We stayed in the Trieste refugee camp for three months, then we were moved to two other camps. There were people in those camps who had been stuck there for ten years—likely never to leave, because they never received a sponsor.

What was life like in the refugee camps?

It was a very interesting world—people of all nationalities were crammed together. Because of the various wars, everyone hated each other—even the children. I stayed with the Hungarians, but there were Romanian and Ukrainian kids, too. You had to watch where and when you went anywhere—there were stabbings. The Italian authorities never intervened inside the camp. If you had a permit card and went outside, the Italians would protect you—but inside the camp, they didn’t care. Every morning, people sat at the entrance, waiting for Italians to come and offer work. Apart from housing and three meals a day, we received nothing else, so we had to earn money.

The only jobs available were temporary, like picking tomatoes or potatoes. There was a circus nearby, and I got a job shoveling after the elephants. Inside the camp, we could clean or work in the kitchen. Every two weeks, they took us on a trip. My mother was hardworking and resourceful. She always pushed me to go see things. We saw Rome, Pompeii, and the Vatican—we traveled all over Italy, which made time pass faster. Meanwhile, we waited every day for our names to appear on the list—to get a sponsor so we could leave the camp. We had to write down a list of preferred destinations. Our first choice was Australia. Second was New Zealand. America was only third. Canada was fourth, because my godfather was there, but my mother didn’t want to go. Fifth was Germany. After a little over a year and a half, we finally got a sponsor—the Hungarian Reformed Church in Cleveland.

‘My sister was detained by the Italians, my mother was beaten by the Yugoslavs, and a Yugoslav border guard held a gun to my ear’

What happened when you finally got on the list?

Once your name was on the list, you had 24 hours before a bus arrived to take you away. You were only allowed one suitcase. A mark was placed on your room door—the next day, a new family would take your place. At that moment, all friendships disappeared. You packed your bag, walked out of your room—and stood aside, while people rushed in to take whatever was left. You just stood there, watching as they took your things. My friend looked at me, put his hand on my beloved bicycle—the one I had worked so hard for—and without a word, he took it. By that night, we didn’t even have mattresses. We sat on the bed frame and waited for the bus until 4am. They took us to the airport, stripped us down, sprayed us with disinfectant, and washed our clothes. Then they put us on a plane.

I will never forget arriving in New York on 7 February 1974. My sister and I ran out of the plane—we had never seen anything like it—and then ran back inside. The five families who had traveled together from the camp stuck together. For a long time, we kept in touch. Two families went to New Jersey. Three of us went to Cleveland. After a few hours of waiting, we boarded another plane. When we arrived, Reverend Endrei was waiting with a large sign: ‘Kovács Family’. He took us in his car and drove us to Buckeye Road, which had once been 80 per cent Hungarian. By then, three-quarters of the residents were no longer Hungarian, but you could still walk safely. Today, it’s more dangerous—but whenever I have business there, I still drive through to reminisce. We were taken to a bank building, where there were three apartments. One of them became ours. They gave us two bags of food, we lay down on a bed full of bedbugs, and the next day, we started working.

Why did you actually leave, and why only the three of you?

I didn’t mention this before, but our family was quite well-off. We had a large house on Váci Street in Pest and another one in Vecsés. My parents were entrepreneurs. My father, György Kovács, ran a tire repair shop on Üllői Road for a long time—he was very skilled and incredibly hardworking. They both worked day and night—not just them, but the entire family. My father had ten siblings, my mother had six. On my father’s side, almost everyone was a merchant—some were even toy makers, and they were very successful at it. So we didn’t leave because of financial reasons.

My mother thought that by leaving, she could get my father out of that world. My father was a good man, and they loved each other deeply. But my mother couldn’t change him—so she thought, if we moved far away, his world would change. She was right to feel that way—but my father didn’t want to leave. And he didn’t come. But my mother was so determined that she left without him. She was a very tough woman—she had even received paratrooper training in Hungary, and she wasn’t afraid of anything. Not even when she ended up working in a Cleveland factory that made bearings. She sent me to train as an apprentice at a family-owned TV repair shop, telling them: ‘Raise my son.’ Not in a parental way—I got plenty of that at home—but still, I look at those two people like they were my second parents. Sometimes I hated them, sometimes I loved them, but I worked there for over ten years.

How did you build your career?

While working, I attended school and later went to university to study electrical engineering. But after two years, I dropped out. I got bored—I didn’t feel like I was learning anything new. Then I joined the Air Force because I wanted to be a pilot—I love flying. But I couldn’t stick with that for more than two years, either, because my life was too fast-paced, and I was always working. At 17, when my mother remarried, I moved out—my sister and I rented an apartment together. I put an ad in the newspaper, saying I repaired TVs and video games—and I got a lot of calls. I was making $200–$250 a week, which was a lot of money back then. I bought a Ford Mustang for $450. Béla, the owner of the TV repair shop, taught me how to drive. He hated driving, so I drove him everywhere. After work, my mother cleaned buildings—and on weekends, she painted houses. She worked seven days a week so that we always had food on the table. The family she cleaned offered her an apartment—with the agreement that whenever a tenant moved out, we’d repaint the place and mow the lawn.

Later, after I quit trucking at 19, I went through the phone book, calling companies until I found one that would hire me. I had always been good with electrical work. After six months, I became a supervisor—and I even hired my mother. I told the owner: ‘She doesn’t speak great English, but everyone will do things exactly as she says.’ That’s exactly what happened. If anyone gave her trouble, she’d slam the table and say: ‘Get to work!’ After I left, she became the boss—they loved her so much, she retired from that company.

Did you stay in touch with your father?

My mother cut ties with him. My sister adored our father, and I always got along well with him, too. I saw him again when I returned to Hungary in 1979—for the first time since defecting. By then, one of my father’s brothers was working for the Ministry of the Interior—he was a major. When I arrived by train from Frankfurt, Germany, they confiscated my permit—they knew exactly who I was. But when I got to Nyugati Station, my whole family was waiting—around 30 of them. My godmother pointed out: ‘See those two men in hats? They’ll be following you for the next three weeks.’ She was right. They were everywhere: when I went to Vecsés to our family home, when I visited the city center, even when I stayed with my cousins. My father visited the U.S. several times, and I also went back to Hungary to see him. When our first son was born in 1995, my wife Eszti and I took him to Hungary at just five months old, so my father could meet his grandson. He passed away the following year—so he never got to meet our two younger children…

Tell us about your family.

I spent two years in the U.S. military because I wanted to go to officer school through my university. But I knew my chances were slim—it was almost impossible to get Congressional approval to become a pilot. Since I was skilled in electrical work, they wanted to assign me to a nuclear division—but I refused. So after two years, I didn’t sign up for six more years—I said goodbye. They wanted me to become a helicopter pilot, but I didn’t like that either. If I had signed the contract, I never would have met Eszti—and I wouldn’t have my family today. Life’s big decisions…

My wife, Eszti, was the group leader of the Cleveland Regös scout folk dance group. She led them for five years. I had known her for years—we worked together in scouting, along with her siblings. She comes from the Fricke family, a prominent noble landowning family in Hungary. She has five siblings. She was born in the U.S. Her parents are still active members of the St. Emeric Hungarian Catholic Church, and they have many relatives on Cleveland’s West Side. Cleveland, as you know, has two sides—and four Hungarian scout troops: the boys’ troop No. 14 and girls’ troop No. 34 on the West Side and boys’ troop No. 22 and girls’ troop No. 33 on the East Side. I was an East Side scout—but I lived on the West Side. So we went to East Side scouting but tried to meet girls from the West Side. There were tea dances where all four troops gathered. I liked working at the bar, because that way I could meet everyone. I remember my scout friend, Laci Globits, forced me to dance with Eszti. I didn’t want to—but he wouldn’t leave me alone, so I finally went. After that, we went out to dinner—and two years later, we got married. Eszti had a huge family—I had a tiny one. So when we got married, my three relatives suddenly turned into three dozen. And most of them were West Siders. I often asked myself: What have I gotten myself into? (laughs)

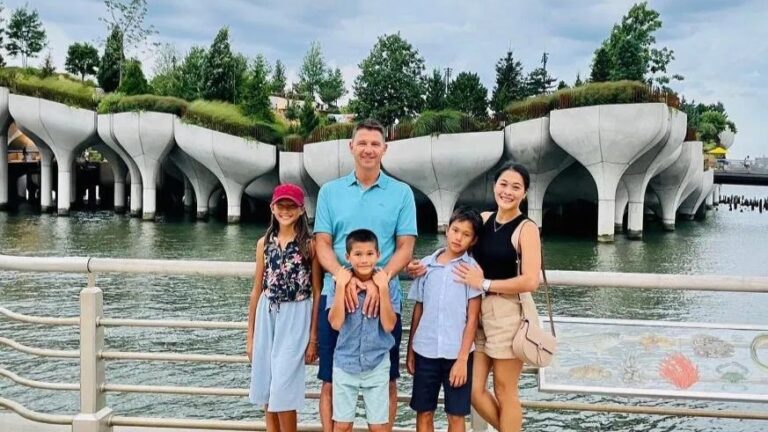

We have three adult children: Gábor (28), Gergely (26), and Erika (21). They all attended Hungarian school, scouting, and speak perfect Hungarian. Erika fell out of scouting when she went to university. She’s an online detective, looking for criminals on the internet, which I never would have thought of her doing. Gábor works with bats as a biologist; he also lived in Australia for six months, working with animals. His wife Emese is also a scout, studying for her PhD in pharmacy; they were married a year ago. Gergő lives not far from us, and he also moved away early and works as a marketer. We traveled a lot together, and the children toured the world. Gergő, for example, went to Argentina with the scouts when he was 12, Gabi and her brother were in Japan recently, and Erika wants to go to Ireland. They also go to Hungary often; I have a big family there, and they are like brothers and sisters with their cousins. In fact, at one time, Gergő was going to move back home to Hungary, but then he realized that he might not be able to live on Hungarian Forints…

Did you alone create this financial stability for your family?

In the beginning, it was very difficult because when I started my business, I had no money—everything I earned had to be reinvested. Eszti had a steady salary, so she could put food on the table and cover our daily expenses. Eszti is a physical therapist—she has been working at the same hospital for 37 years and now leads one of its departments. As for me, I currently run an IT company. We primarily set up computer systems in dental and law offices. I originally knew nothing about IT, but I learned it over time. This is already my third business. Previously, I had a fleet of 26 large trucks that delivered and installed refrigerators and washing machines. We had over 30 employees and did this for five years, providing 200 appliances per day. But there were times when I couldn’t pay my workers, and I had to borrow money just to cover their weekly wages. Before that, I had a TV repair business. At the time, people were installing speaker systems and home theaters in their houses.

‘There were times when I couldn’t pay my workers, and I had to borrow money just to cover their weekly wages’

Each time I switched businesses, I had to start from scratch. My mother always told me: ‘Son, if something doesn’t work, leave it behind and move on. No one is going to save you.’ And that’s exactly what I did. Whenever I needed business advice, I’d visit Pista Gráber, who owned a custom steel manufacturing company that catered to the industrial sector. He was a fantastic man—he had built his business from the ground up and had a wealth of experience. He always helped me because he knew what it was like to start from nothing. He even helped fund the construction of the Cleveland Scout Home out of his own pocket. He donated a lot to scouting and churches—he was a good man. He passed away in 2010.

What about your faith?

Eszti and the kids are all Catholic—my mother and sister were Catholic, too. I’m Lutheran, like my father. During Communism, in the 70s, religious practice was severely restricted. Despite this, we attended catechism because my parents believed it was important, but we didn’t go to church every Sunday. When Eszti and I got together, the priest had to be convinced to let us have a Catholic wedding, and I had to agree to premarital counseling, and I went through with it properly. We got married at St. Emeric Church, with over 400 guests—people around here had never seen a wedding that big. I later realized that in other families, parents of different faiths sometimes argued over their children’s religion—and I didn’t want that. So I left that 100 per cent up to Eszti. At the same time, I fully contributed to the family’s logistics. I’ve probably attended more Catholic services than Lutheran ones. And I don’t care about denominations—if someone needs help, I help them, no matter what church they belong to.

How did you get involved in scouting?

When my mother heard about scouting, she called Commander Viktor Simonyi, who told her: ‘Have your son stand outside your house—I’ll pick him up and take him to scouting.’ Since he lived nearby, I stood outside, and he picked me up. I got into the car, and in the front seat was Zsolt Gregora—a huge guy who was the assistant scoutmaster. Next to me sat a quiet boy with big glasses, who was a year younger than I was. And in the back seat—which I didn’t notice at first—was a large, snarling German Shepherd that nearly bit my ear off. That’s how it all started.

My sister also tried scouting once, but she decided it didn’t fit into her schedule. Marika was more mature for her age, and she decided she’d rather work. She’d wake up at 4am, go to a bakery to make bread, then go to university, where she studied design. She later worked for Nestlé for many years. She recently passed away from cancer. She had a daughter, Megan, who is 30 years old and has four children. Megan is also a scout, and she even brings her eldest son to Hungarian scout programs.

I was the new kid in the troop, but on the first day, Laci Kozmon put his arm around me, showed me around, and didn’t let anyone pick on me. He told me: ‘In our troop, there’s no division—no one gets excluded.’ From that troop, eight of us are still close friends to this day: György Kozmon, Lajos Szigeti, Mihály Horváth, Viktor, Simonyi Jr., Laci Kozmon, Géza Kovács, Imre Pallai, György Brenner, Tibor Ország, and János Szigeti. Later, Tivadar Lukács joined us. These friendships run so deep that if I called any of them anytime and said I was in trouble, they’d be here immediately. In 1975, I went to my first Jubi Camp, where I wrecked myself: little sleep, new shoes, bleeding all over…

Yet, you’ve been going to Fillmore ever since?

Yes! In 1976, I attended the leadership training camp—that’s when I met Imre Lendvai-Lintner, the current president of KMCSSZ (Hungarian Scout Association in Exteris), and the others. They asked me to come back as a patrol leader, and later, I became an assistant troop leader in 1979. In 1980, there was another Jubi Camp, and after that, I returned to work at the leadership training camps for 15 years. Then, for a while, I stopped coming—because I had a lot going on in my life. I spent that time traveling the world—literally. That was my obsession for a while. That’s why, later on, we also let our kids travel. Education is important, but real learning happens when you go out into the world. You see how others live, you compare it to your own life, and you learn how to navigate different cultures—all comes from scouting, that’s the beauty of it.

‘Education is important, but real learning happens when you go out into the world’

But scouting isn’t always perfect. Sometimes it pulls people away from their families or even work. We always teach that you should prioritize your home, work, and family—and only then focus on scouting. But in practice, that doesn’t always happen. Some people pour their entire lives into scouting—even when they could have advanced further in their personal or professional lives. Me? I traveled the world, and I drove trucks for two years before settling down. I didn’t get married until I was 30. My mother always told me: ‘Son, don’t tie yourself down too early—go see the world and learn from it.’ So I did. I had so many adventures, but I’ve never been seriously hurt. I’ve always taught my kids: If you stand up straight and speak with confidence, people will listen to you, and they won’t be able to do anything against you. Be decisive, whether you’re dealing with a person or a government official. If you know what you want and it’s right, go for it.

You are the director of the Sík Sándor Scout Park and the scoutmaster of Cleveland’s Scout Troop No. 22. How did you get here?

Back in the 1990s, we had to merge Cleveland’s four scout troops. In one, there were mostly older scouts, and in another, there were mostly younger ones. At the time, it was a big deal—parents didn’t like it, many dropped out, friendships were strained, but it was a long-term decision. All four troops survived, and troops No. 22 and 33 became adult scout troops. The younger kids went into the western-side troops, which were closer to downtown. Today, the adult women’s troop mainly does charity work, raising money and clothing for Hungarians across the border. Meanwhile, we spent years helping the younger troop when they didn’t have enough leaders. Later, we decided to support them financially and with physical labor, organizing Cleveland’s huge Scout Day and maintaining Fillmore’s Scout Park. There are 24 of us, and most of us have worked at both places.

For example, years ago, I ran the outdoor kitchen at Scout Day. I love to cook, and I’m good at it—that’s why I rebuilt the kitchen in Scout Park. In 25 years, there have been five Jubi Camps here. Our troop played a huge role in planning programs for the subcamps. Sometimes, the KMCSSZ leadership looked at us sideways because we were ‘different’: we had slightly different uniforms, with tribal caps, and we didn’t like outsiders interfering in our work. But over 30–40 years, we accomplished a lot of great things.

In 2011, Imre asked if we would like to help Zoli Lapmerth, who ran this Scout Park for 30 years. At that time, the Hungarian government started to support the diaspora, and money was available for development, but KMCSSZ did not have enough funds of its own to maintain the park, and things started to fall apart. The infrastructure was getting old. When I started coming here, we sat down with Imre and Zoli and discussed what projects we could do every year. Imre got money, but not only from the Hungarian government: As people saw that something was happening here, they were more willing to give, so money started coming in from donations, which didn’t always happen before. Then we started working, and I brought the team. First, we built the rooms for the headquarters, so that when we came here in the winter, we wouldn’t be living in tents. Everybody reached into their pockets, and at Imre’s suggestion, we pre-sold the rooms, so now we have six rooms with names on them. Then we replaced the toilets outside. I first phoned all over the world, found a place in northern Canada, and brought them from there.

Over time, we became very good friends with the Amish in the area, who are excellent craftsmen and hardworking people. I have four Amish friends in the area who welcome me into their homes as if I were family. Together, we rebuilt the infirmary, adding accommodations beside it, then renovated the main building, and restored the Homeless Eagles’ House—named after the founders—which also has lodging. The small kitchen was also falling apart, so we redesigned and renovated it. We inaugurated it last year, along with the main building. During the COVID pandemic, the Amish worked on the exteriors, while we renovated the interiors. We came here to work year-round, in winter and summer alike. With temperatures dropping to -7–8°F (-22°C) and snow so deep we couldn’t even drive into the park, we had to call friends to help plow a path. That was the last time we saw Zoli bá—even in his final years, at 90 years old, he was here every single day. Many others helped, too—like Tivadar Lukács, an amazing Transylvanian man, who wasn’t a scout as a child, but later married a scout girl from the West Side. He was so enthusiastic and we got along so well that ten years ago, we officially inducted him into the Scout Troop No. 22, with a proper ceremony. He broke down in tears. When do you see a Szekler man cry? Never.

When did you become park director? Is it a lifetime commitment?

Two years ago, after Zoli bá passed away, Imre asked me to take on this role. But honestly, nothing really changed—I’ve been doing the same work ever since. Right now, as we prepare for next year’s Jubi Camp, we’re building a large storage facility—because we have a ton of equipment, and the mice eat everything. Besides that, we want to create another building, since one of them we’re currently renting from the neighbors. That will be the last major project of my ‘career’, because I don’t think we need more. We’d also love to get mobile showers, but that’s a huge undertaking—not just buying them, but also installing water and electricity for them in the new section of land we purchased a few years ago to expand the park.

If all goes well, I’ll find my replacement soon. It’s really hard to balance my business and family with this work. Even Eszti says she barely sees me and reminds me that there’s plenty to do around the house, too…Just to give you an idea: Since January, I’ve spent 19 weekends here, plus several weekdays, and I’m here for all ten days of this summer camp—that’s how it is every year. Sometimes, I drive up here twice a week. A lot of times, there’s something urgent to take care of. But other times, I come just for a conversation—because you can’t talk to the Amish on the phone. Even if it’s just a two-minute discussion, I have to drive here, handle it, and then drive back home. That’s almost a four-hour-long drive—one way.

Can you imagine leaving the scouts and never coming back?

I’ve always said that the day I step down, I’ll only come back as a visitor. I love this place, but why would I interfere with someone else’s work? They’ll have their own vision, their own plans. I don’t want to be the guy standing over their shoulder, telling them what to do. Just like I never let anyone micromanage me—I’ve run my own business since I was 17 years old. Even Imre is retiring soon—he’ll need to find his successor too, and we might not want to work together with whoever that is. But I’d be happy to mentor the next park director. I’ll work for a few more years, then hand over the keys. I’ll watch from afar, quietly, and then move on to the next adventure. But the Cleveland troop and my friends will always remain. After all, in 1951, we were the first scout troop formed by the KMCSSZ in North America…

Read more Diaspora interviews: