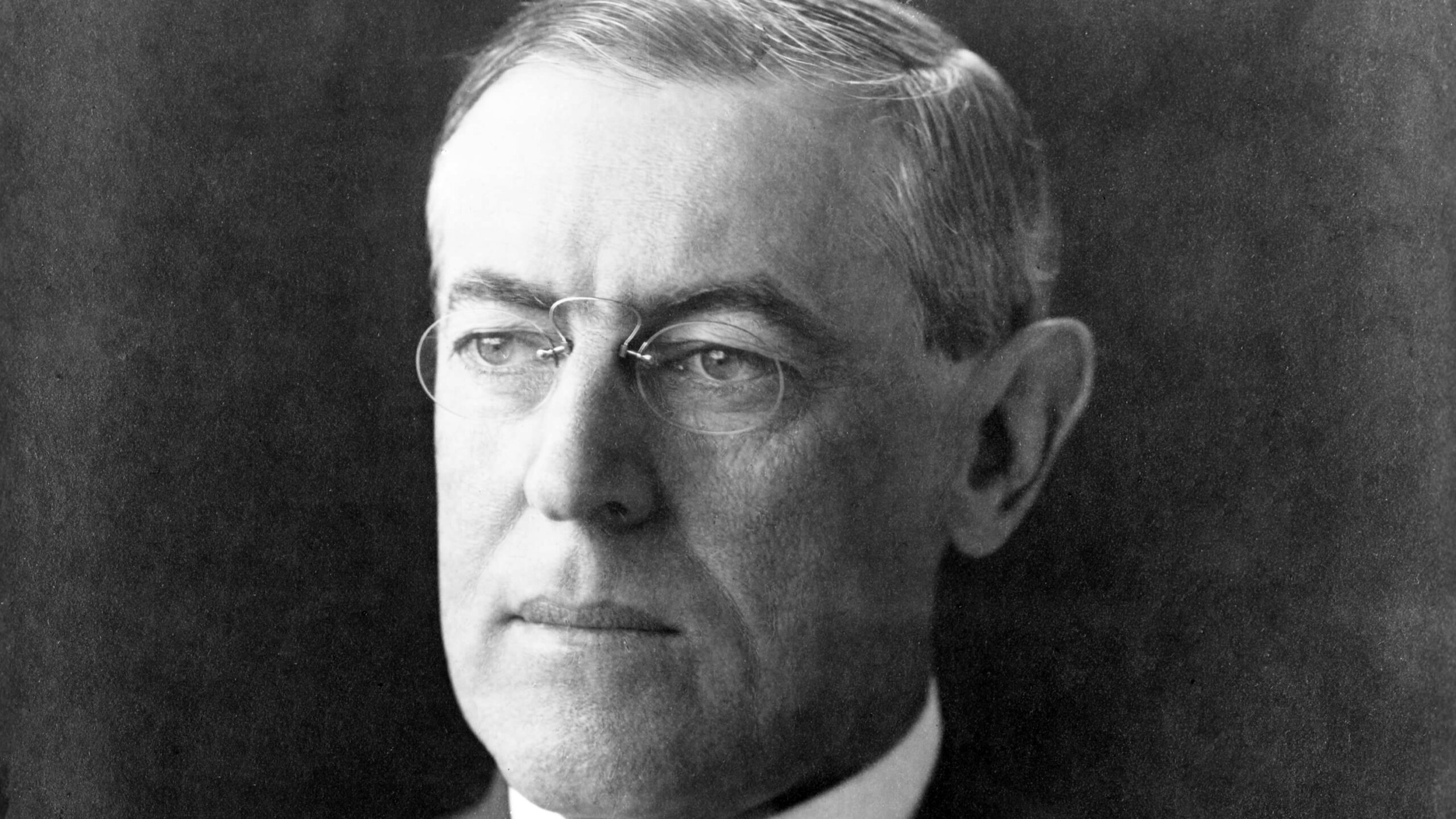

Last month on 28 July was the 110th anniversary of the beginning of the Great War (World War I). At its outbreak, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson (in office 1913–1921) kept America out of the fighting by proclaiming the nation’s neutrality. While attempting to mediate between the belligerent countries, he soon found himself engaged in a diplomatic upheaval to defend the rights of neutral states.

After his unsuccessful diplomacy, Wilson was pressured to break off relations with Germany—and also with its ally, the Austro-Hungarian Empire—after the Germans announced on 1 February 1917 that they would resume unrestricted submarine warfare against U.S. merchant vessels. President Wilson, notwithstanding that just a mere handful of countries were democratic, like Britain, France, the Russian Provisional Government, and Switzerland, asked Congress during a joint session on 2 April 1917 to declare war on the grounds that ‘The world must be made safe for democracy.’

In essence, the president had made an appeal for the ‘globalization of the Monroe Doctrine’,

i.e., an international order in which democracy was going to establish a politically plural world whereby national self-determination (a phrase Wilson used constantly after 1914) would be the rule of law.

In light of the inherent warlike and unstable body politic of the absolute monarchies, which oversaw saw the mobilization of more than 65 million soldiers, and the deaths of almost 15 million military personnel and civilians combined during the Great War, Wilson thus formulated his League of Nations—a precursor to the United Nations. Although it would never be approved by the U.S. Senate, the Wilsonian notion conceived in an era of nationalist passion became a blueprint for state construction composed of a liberal democracy. It was perhaps the most important contribution to U.S. foreign policy up to that time.

America’s entry in the war helped the Allies defeat Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, putting the U.S. on the path to assume the global leadership it has today. Although this role would only be substantially assumed after World War II, it was President Wilson who paved the way for a rules-based order embedded in a set of international institutions.

The U.S., despite its geographical isolation from Europe and Asia, eventually established a strong international balance for the survival of democracy:

- The occupation and reconstruction of Japan (1945–1952): under the leadership of General Douglas A. MacArthur, the U.S. implemented military, political, economic, and social reforms, so Japan could create infrastructure for its people.

- The Marshall Plan: officially called the plan for European recovery, was announced in a speech by U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall on June 5, 1947; it was one of the U.S. political-economic plans for the reconstruction of Europe after World War II in which over 12 billion dollars were allocated.

- The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO): the embodiment of the League of Nations conceived by President Wilson after the First World War. It provided that in the event of an attack on a member country, the members of the alliance—now made up of thirty-two countries—were required to meet and decide what measures to adopt to ‘re-establish and maintain the security’ of the contracting parties against any external attack.

With the creation of NATO, for example, the U.S. prevented the Soviet Union from conquering the entire European continent—the Eastern European countries the Communist Russians took over in the 1950s had not yet been part of the Alliance. Even today, the Atlantic Pact continues to defend those nations susceptible to a Russian threat, such as the Baltic countries. And, to a certain point, by providing Ukraine with unprecedented levels of support, it has helped the Ukrainians uphold its fundamental right to self-defense against the Russian Federation.

What one can classify today as a Wilsonian world order materialized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was to be carried out by institutions like the United Nations, the International Court of Justice, and the World Trade Organization. This concept, that of global security, was nothing new, for it had been introduced by Russian Tsar Alexander I at the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815); he articulated a concept of an international system that would rest on a moral consensus sustained by a concert of powers that would operate from a common set of principles about legitimate sovereignty.

The last U.S. president who effectively applied the Wilsonian concept was Ronald Reagan (in office 1981-1989) with his ‘constructive engagement’. Originally conceived to promote an alternative to the economic sanctions and divestment from South Africa called for by the international community, it sought to advance regional peace in the African continent by linking the end to both South Africa’s occupation of Namibia and the Cuban presence in Angola. In essence, Reagan’s goal was to ease authoritarian U.S. allies, as he did with the Philippines and the Soviet Union, so that liberal democracy could embed itself in such countries.

The Wilsonian concept began to wither under Present George H. W. Bush (in office 1989–1993)

who infamously sneered that he lacked ‘the vision thing’, and was laid to rest when President Bill Clinton (in office 1993–2001) announced that ‘the containment of communism’ would be replaced by ‘the enlargement of democracy’.

Critics often decry Wilson’s foreign policy approach as wishful thinking. On the contrary, says Walter Russell Mead, Professor of Foreign Affairs and the Humanities at Bard College, ‘as Wilson demonstrated during the negotiations over the Treaty of Versailles, he was perfectly capable of the most cynical realpolitik when it suited him’. It is not that President Wilson was naive or an ideologue. Instead, Mead explains, he had ‘a simplistic view of the historical process, especially when it comes to the impact of technological progress on human social order’.

Wilson was not just a Presbyterian by faith, he was the devout son of a minister, deeply ingrained in the Calvinist teaching of predestination and the utter sovereignty of God. Believing that the arc of progress was preordained, the future would thus fulfil biblical prophecies of a coming millennium: a thousand-year reign of peace and prosperity before the final consummation of human existence, when a returning Jesus Christ would unite heaven and earth. This was the drive of his foreign policy, which mirrored his domestic accomplishments that included:

- the Federal Reserve Act (1913): created a central bank and regulated the financial system;

- the Underwood-Simmons Act (1913): re-established a federal income tax and lowered tariff rates;

- the Clayton Antitrust Act (1914): strengthened antitrust laws and prohibited monopolies;

- the Federal Trade Commission Act (1914): created the Federal Trade Commission to investigate unfair business practices and regulate interstate commerce;

- the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act (1916): prohibited interstate commerce of goods made by child labor;

- the Adamson Act (1916): established an eight-hour workday for railroad workers;

- the 19th Amendment (1920): granted women the right to vote.

When Joe Biden took office, he pledged to uphold the principles of democracy against the lawlessness of autocracy. His administration was able to reinforce and strengthen the solidarity among advanced democracies by keeping the Chinese and Russian autocracies in check. Yet there was a dichotomy in Biden’s s foreign policy, which resulted from his entrapment of a morally enigmatic world. In the Middle East, for example, Biden, who had accused Arab dictators, like Prince Mohammed bin Salman, of being pariahs, eventually had to recognize them as vital partners. And, while he supports Israel’s ‘right to self-defense’, he has inadvertently assisted in the killing of tens of thousands in Gaza and the displacement of approximately 1.8 million people, which is 80 per cent of the population—this mirrors what the Trump administration did in Yemen when it provided arms to the Saudis.

American interests are always intertwined with its core values, at least in theory—

at times such interests have been proven to be nothing other than economic colonization.

All things being equal, the reason the U.S. continually officially engages in a rivalry for supremacy is because it dreads the idea that powerful autocracies will make the world unsafe for democracy.

At times the only way to make the world safe for democracy, as Wilson envisioned, is to assume an amoral position, which may require a courtship of impure partners, even at the risk of tolerating their immoral policies. Yet notwithstanding the apparent Wilsonian recession in the U.S.-led West, and for that matter, the rest of the world, President Wilson’s vision is so heavily rooted in American political culture that its values shall continue to have a global appeal as proven by the recent prisoner swap between the U.S. and Russia, which involved at least five other countries, including Belarus, Germany, and Turkey.