In 1824, a historic anomaly took place: the House of Representatives chose the President of the United States. It is (so far) the only such occurrence since the modern electoral system was adopted by the passing of the 12th Amendment of the Constitution in 1804.

This could happen because multiple candidates, all from the same party, had strong regional support in different parts of the country. Five candidates from the Democratic-Republican Party had significant backing—however, only four of them managed to win electoral votes. They were Andrew Jackson from Tennessee, a Major General in the US Army; John Quincy Adams from Massachusetts, son of former president John Adams, who was the sitting Secretary of State; William H. Crawford from Georgia, the sitting Secretary of the Treasury; and Henry Clay from Kentucky, the serving Speaker of the House.

In her 1996 paper, Professor of Political Science Robin Kolodny from Temple University wrote that, despite it being a common misconception, the unusual result of the 1824 election does not mean that there were no major national issues at the time. Nor does it mean that the election was decided solely on the candidates’ characters. As she puts it: ‘Regional divisions cleaved along two central issue dimensions: the relative strength of nationalism (the power of the federal government vs. the power of the state governments) and the nature of political participation (elitist vs. egalitarian republicanism).’

To the latter point about ‘elitist republicanism’, the author later cites that six (Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, New York, South Carolina, Vermont) out of the 24 states that were part of the USA at the time did not even allow popular voting in presidential elections. Rather, the state legislatures chose the state’s electors. On the former point about the power of the federal government, the main issues at the time were the implementation of protective tariffs and the funding of public road construction.

Tariffs had always been a major issue in presidential campaigns in the 19th century as they were the main source of revenue for the federal government.

There was no permanent federal income tax in the US until 1913, under the first Woodrow Wilson administration. President Abraham Lincoln did impose a 3 per cent federal income tax in 1862. However, that was only a temporary measure to fund the Union’s Civil War effort and was repealed in 1865.

As we wrote above, tariffs were also a campaign issue in 1824, the election with the most peculiar result in American history. While Andrew Jackson won both the most electoral votes and the popular vote, he failed to win the 131 electoral votes needed for a majority. Thus, the selection of the next president fell to the House of Representatives. There, each state’s caucus received one vote: now 13 votes out of 24 were needed to win a majority. Only the three candidates with the most electoral votes were still eligible. John Quincy Adams received exactly 13 votes, after Henry Clay (who finished 4th and thus was out of consideration) gave his support to him, and spoke ill of both of the other candidates still in play, Jackson and Crawford. Since Clay was also the Speaker of the House at the time, he had a huge influence.

After Adams took office, he named Clay as his Secretary of State. Jackson, enraged as he felt he’d been robbed of the presidency, used this to paint Adams and his people in government as elitist and corrupt, ignoring the will of the people. He dubbed the appointment of Clay as the head of the DOS as a ‘corrupt bargain’—and that term stuck even with historians of today. However, Clay’s high position in the cabinet was not the only reason why Adams won the vote in the House.

Daniel Feller, a professor of history at the University of Tennessee, points out in his article that Andrew Jackson was an outsider compared to the three other men vying for the office of the presidency, as he had never served in a position in the executive branch, and had resigned from the Senate just six months after being elected in 1797 for simply finding the job too dull. Instead, he rose to be a national figure as a military leader, serving as a Major General in the War of 1812. That is why, ahead of the historic presidential vote in the House, Clay dismissed him as a mere ‘military chieftain’, unfit to be president.

Evidently, Andrew Jackson challenged the incumbent President Adams four years later in the 1828 election. During the campaign of 1828, the surrogates of Adams still tried to portray him as a bloodthirsty warrior wanting to become a tyrant; while the Jacksonians (known as ‘Democrats’ only colloquially at the time) tried to portray President Adams as a corrupt, libertine aristocrat. However, as for where Jackson stood on practical issues, such as high tariffs, his surrogates campaigning for him never gave his positions away. They didn’t even have to—Jackson’s popularity and his perception of being a ‘common man’ were enough for him to get a decisive victory over the incumbent Adams.

Please note that at this point in time, the candidates themselves are not campaigning. Their surrogates, such as local newspaper editors, pamphleteers, and orators are doing that for them. The modern form of campaigning did not become the norm until the early 20th century.

By his reelection campaign in 1832, however, President Jackson was very publicly against the ‘American System’, a phrase coined by Henry Clay, a protectionist-federalist economic policy.

In his first term, Jackson vetoed the charter of the second National Bank of the United States and lowered tariff rates. Andrew Jackson’s new Democratic Party held their first convention in Baltimore, Maryland in May 1832. They beat Henry Clay, running as an ‘anti-Jacksonian’ Democratic-Republican, known as a ‘National Republican’ at the time, in that year’s presidential election.

To oppose Jackson’s Democrats, a new political party, the Whig Party was founded in 1833. It was a loose coalition of American politicians who had little in common other than their dislike for President Jackson, then President Van Buren, who was also Jackson’s Vice President for his second term. In that sense, they were much akin to the United Opposition that ran in last year’s Hungarian parliamentary election.

The financial crisis known as the Panic of 1837 gave the Whigs the opportunity to have their first president elected, William Henry Harrison in 1840. He shortly after became the first president to die in office, falling to pneumonia only 31 days after his Inauguration. This established the precedent of the Vice President taking over the office in such case, thus John Tyler became the tenth President of the United States.

However, President Tyler was not re-nominated by his party for the 1844 election. Instead, they went with a familiar name: Henry Clay. In their official party platform, they emphasized strong federalist values, such as ‘a well-regulated currency; a tariff for revenue to defray the necessary expenses of the government, and discriminating with special reference to the protection of the domestic labor of the country’ and ‘the distribution of the proceeds of the sales of the public lands’.

They focused on economic messages: they claimed that the country’s most prosperous years had been when the government was run according to Clay’s American System principles. They also paid tribute to the founding fathers, and drew attention to the fact that their VP nominee, Theodore Frelinghuysen’s father had fought alongside George Washington at the battles of Trenton and of Monmouth during the Revolutionary War.

However, the Whigs cautiously avoided mentioning two pressing controversial issues at the time: the expansion of slavery and the annexation of Texas. As opposed to the Democrats, who in their 1844 platform proclaimed that Congress has no power to interfere in the issue of slavery, only the states’ governments do; and that they are firmly for the annexation of Texas and the claiming of Oregon territory from the United Kingdom. They nominated James K. Polk, the former governor of Tennessee, for president. Not only did he win, but he also accomplished all his campaign promises during his first term in office. He did not seek a second term as he pledged.

The 1848 election was a great example of how ideologically uncommitted the Whig Party was. When the war with Mexico broke out over the annexation of Texas, not only did Whig representatives in the House vote against it, but they were also very vocal critics of it. However, when the tide of the war quickly turned in the US’s favor and thus the war became very popular with voters, they changed their minds immediately. They even nominated Zachary Taylor for president, an otherwise apolitical Major General in the US Army who served heroically in the Mexican conflict. The ploy worked and Whigs managed to win their second (and last) presidential election in 1848.

Between 1848 and 1856, the issue of slavery became even more contentious in the US. The terms of the Missouri compromise of 1820 started to get ignored. New states admitted into the Union did not want to be bound by the ‘line of scrimmage’ drawn in 1820 anymore, nor did they care about the free state-slave state balance.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 completely did away with the Missouri compromise, and allowed for so-called ‘popular sovereignty’ for the new states. That meant the population of each state got to decide whether they wanted the institution of slavery allowed in their states. This, in turn, led to violent conflicts in the new state of Kansas, as pro-slavery and abolitionist radicals rushed there to tilt the balance in their favor, often clashing with each other. This period is known as ‘bleeding Kansas’ in American history.

New legal developments such as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the Supreme Court decision in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case in 1857 made it seem like the pro-slavery side was becoming the predominant one in the country.

In the meantime, a new political party, the Republican Party was founded in March 1854.

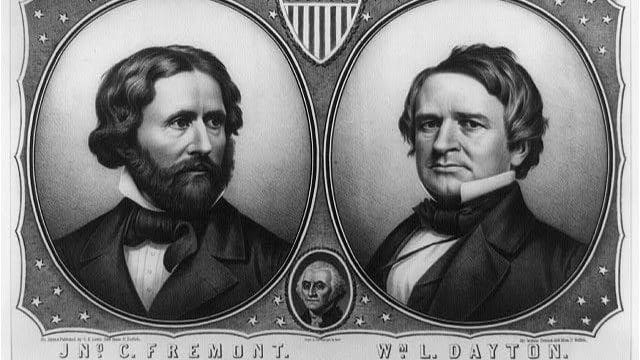

They first nominated a candidate for president in 1856. It was John C. Frémont, a former Senator from California.

In their official 1856 party platform, they proclaimed that they wish to admit Kansas as a free state, and ban slavery in all places that are US territories (but not states), just like the founding fathers intended it to be. They also vowed to ban polygamy among the Mormon communities in Utah territory. As they wrote: ‘the Constitution confers upon Congress sovereign powers over the Territories of the United States for their government; and that in the exercise of this power, it is both the right and the imperative duty of Congress to prohibit in the Territories those twin relics of barbarism–Polygamy, and Slavery’. What’s more, they professed that they wish to punish the Kansan mobs for the atrocities they committed. Also, they wrote that the Federal Government under their administration would fund the construction a transcontinental railroad system from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean; as well as provide funds for the improvement of rivers and harbours to facilitate better commerce in the US.

Frémont lost the 1856 election to Democratic James Buchanan. In 1860, however, the second Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln won. Despite emphasising that he did not want to free the slaves in Southern slave states, and only wanted to stop the spread of slavery, Southerners did not believe him, partly because his administration included ardent abolitionists, such as Secretary of State William Seward.

In December 1860, before Lincoln even took office, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union. By June 1861, ten more states followed suit. When Confederate forces raided the federal armoury in Fort Sumter, South Carolina in April 1861, the American Civil War broke out. It lasted for four years, ending in April 1865 with a Unionist victory.