The following is a translation of an article written by Emese Hulej, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

The 20th century in women’s reading. Artists, scientists, legendary educators, lifesavers, and society’s favourites. With doctorates, oeuvres, noble titles, beauty, and inspiring stories. The struggles of a Hungarian female scientist and teacher from Kolozsvár (today’s Cluj-Napoca, Romania) in the shadow of war and Trianon below.

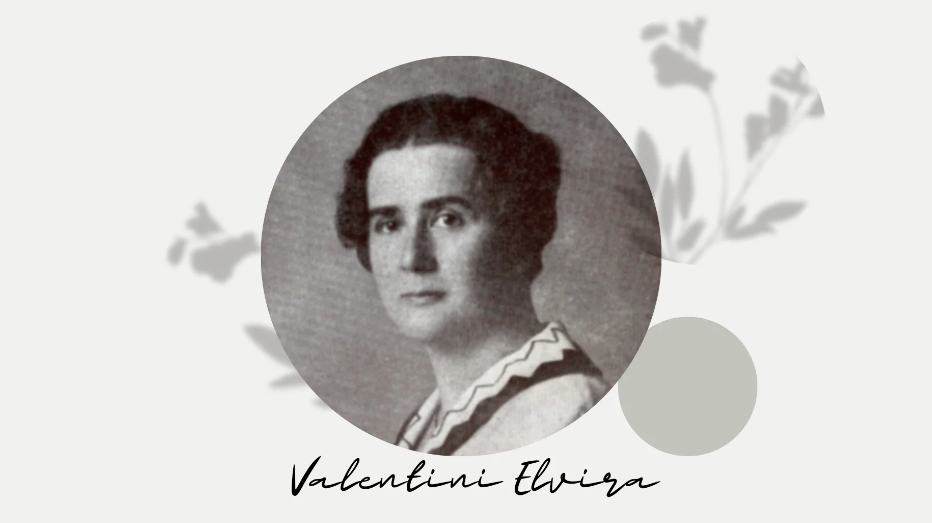

A young woman stands on the beach in Fiume (also Rijeka, Croatia). Looking at the water, she thinks that from now on she will be able to enjoy this view for many years to come. Elvira Valentini, born in Kolozsvár, arrived in the coastal city in January 1914 to teach natural history, botany, and chemistry to students at the state secondary girls’ school. She herself requested her transfer from Kolozsvár, where she worked as a university lecturer.

However, even though she was the first Hungarian woman in this position, she knew she could wait decades for an appointment, even as a substitute private lecturer. She had always been interested in the flora of the Balkans, a subject her former professor had instilled in her, so she decided to make a change. She thought that in Fiume, after teaching, she would explore the countryside and continue her scientific work.

But that was not to be. A few months later, war broke out, and her family called Elvira home, asking her to stay there. The shot fired in Sarajevo thus marked not only the beginning of the First World War, but also the end of an ambitious Hungarian woman’s scientific career.

Elvira’s father, Adolf Valentini, was a well-known pharmacist in Kolozsvár who ran the Holy Trinity Pharmacy in Belmonostor Street. He was also involved in aerated water production and soon set up his own factory. He went hunting, attended social gatherings and gardening clubs, and was also a member of several scientific and educational associations, including the Natural Sciences Section of the Transylvanian Museum Association, which Elvira’s daughter also joined years later. He gave his children surprising names: Elvira, Auróra, Zulima, and Armand.

‘The shot fired in Sarajevo…marked not only the beginning of the First World War, but also the end of an ambitious Hungarian woman’s scientific career’

Elvira studied at a Reformed girls’ school, where she was most interested in botany. After a 1895 ministerial decree allowed women to enrol in medical faculties and humanities at universities, she took extra lessons in Latin and, together with some of her female classmates, applied to take the graduation exam at the Piarist secondary school. Two of the five outstanding examinees were girls, one of whom was Elvira.

This is how she got into the University of Kolozsvár, where she became a demonstrator in the botany department in her third year, later becoming an assistant professor and even passing her doctoral degree and examination for professorship. Her thesis was published in Múzeumi Füzetek (Museum Notebooks), the first scientific botany paper written by a Hungarian female botanist to be published in a domestic journal.

She was also a pioneer in that she won a two-year state scholarship, which allowed her to study at universities in the Netherlands and Poland, attend lectures at the Sorbonne, and conduct research at the Department of Plant Anatomy in Fontainebleau.

While studying the world of mosses, molds, and bacteria, she spent her free time cycling with her fellow students, visiting jasmine and tulip fields, and botanical gardens.

‘The Romanian government made Hungarian-language education as difficult as possible’

After her scholarship ended, she returned to university and then signed a contract in Fiume. Returning to Kolozsvár, she taught at her former school, and after the Romanian occupation and the Treaty of Trianon, she followed the rocky path of minority teachers, as she put it. The Romanian government made Hungarian-language education as difficult as possible, forcing it into church schools.

However, even there, new and stricter regulations were gradually introduced. Elvira learned Romanian, wrote notes to replace the missing textbooks, and remained a cheerful, calm teacher whom her students adored all along. Author Rózsa Ignácz remembers her most vividly for her beautiful black eyes and her ability to inspire enthusiasm for her subject even in a student rather inclined toward the humanities.

Elvira even took on the role of director to help promote Hungarian education. Nevertheless, there came a point when she felt she no longer had the strength to fight. In the summer of 1927, after many fruitless struggles, she moved to Szeged to escape her apathy and burnout, where she ran the girls’ section of the university boarding school. However, this was more of an educational than a teaching role, so she requested a transfer to Szombathely, to the State Kanizsai Orsolya Girls’ Secondary School, where she taught geography, natural history, and chemistry at her usual high standard.

In the second half of the 1930s, she was already in poor health and soon retired. She moved back to Szeged, close to her siblings who had also relocated there. She died in the winter of 1942 during the Second World War in the city on the banks of the Tisza River, and she was also buried there.

Read more about famous Hungarian women:

Click here to read the original article.