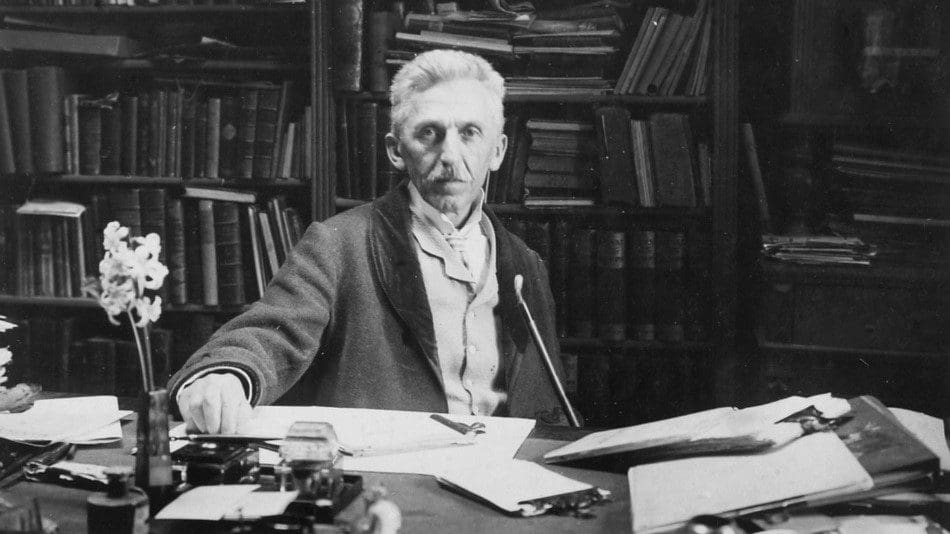

The scion of a Hungarian family of German ancestry and in his final years, the resident of the scenic rural town of Eger, Géza Gárdonyi is probably best known for his classic historical novel Egri csillagok (The Stars of Eger, translated to English by T. László Palotás), telling the tale of the Hungarian soldiers who defended the Eger castle against the Turks in 1552. Gárdonyi’s father, Sándor Ziegler was from a family of German ironworkers who had lived and worked in the Sopron area for centuries. He was already a wealthy factory-owner at the outbreak of the Hungarian War of Independence in 1848–49, when, driven by a patriotic sentiment, he left Vienna and gave up financial security, distinguishing himself as ‘Kossuth’s arms manufacturer’ in the fight against the Habsburgs. When the revolution was crushed, he was arrested and court-martialled, but thanks to the testimonials of powerful protectors he was acquitted, and lived in voluntary exile in Vienna until the 1850s, when he settled down in Hungary again. This grand ancestry had probably defined the young Géza Gárdonyi, who became on of the most well-read authors of the century.

Gárdonyi was born on 3 August 1823 in Agárdpuszta near Lake Velence — hence his pen name, chosen after the name of another Lake Velence settlement, Gárdony, in the vicinity of his birthplace. He worked as a teacher before he became famous thanks to his first novels depicting rural Hungarian life, such as Az én falum, 1898 (My Village), and later with his grand historical novels (Egri csillagok, 1901; A láthatatlan ember (Slave of the Huns, also known as The Invisible Man), 1902; Isten rabjai (Prisoners of God), 1908).

Gárdonyi is also revered as the author of early Hungarian psychological novels, and although his work as a poet and dramatist proved less lasting, it is also significant. He also published a number of essays and articles in Hungarian newspapers on topics ranging from economics to wine-making and chess. Upon his death, one newspaper commented that ‘he never forgot that he himself was the son of this sweet mother earth, and he was happy to capture the images of village men, girls and old women to immortality’ in his works.[1]

Several of his works were turned into highly successful films, most prominently the 1968 The Stars of Eger feature film, directed by Zoltán Várkonyi.

Stars of Eger trailer

Two young Hungarian children, an orphan boy and a young noble girl, are kidnapped by a Turkish slave trader, although, thanks to the cleverness of the boy, they are able to escape. Years later, the young boy must again defend the girl from Turks, only this time there are 200,000 Ottomans against only 2,000 Hungarians in the Fortress of Eger.

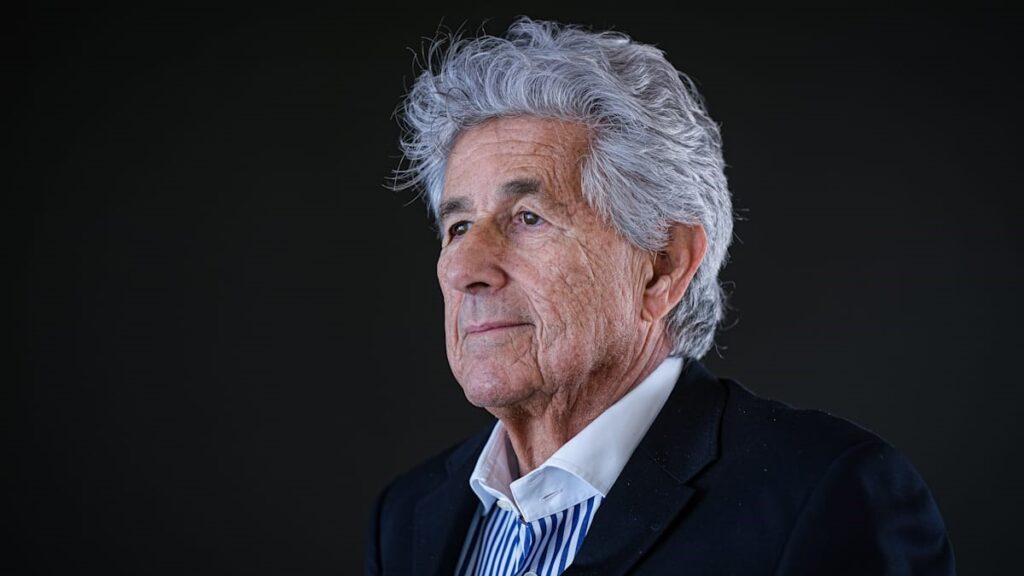

As is often the case with great authors, Gárdonyi’s legacy was hijacked by the Communists after WWII.

While in 1948 the Communist daily Szabad Nép suggested that he be ousted from Hungarian literature,[2] this hostility was oddly replaced by the lauding of his ‘democratic’ and socially sensitive works took from the fifties to the seventies,[3] likely due to the fact that a writer of his merits could not be simply eradicated from the annals of Hungarian literature.

One common—and mistaken—idea is that Gárdonyi avoided joining ‘groups’ within Hungarian literature. In reality, in an interview in 1920 he said: ‘Since the [18]90s Hungarian literature has been divided into two groups. First there was a smaller, but now larger one, the literature of new Hungarians from Pest. Foreign literature written in Hungarian. But written in bad Hungarian, strange sentences, Hungarian, but alien to us. What treasures can such a literature give us? There is a difference between arany (gold) and aranka (a weed).’[4] In 1920, he penned a poem titled ‘The Fifth Sword. A Greeting to the Soldiers of Horthy in Eger.’ ‘Touch your swords upon the stones / of this castle, knights of Horthy’, the poem read.[5] In 1921, he joined the National Alliance (Nemzeti Szövetség) on the side of Cécile Tormay, Ferenc Herczegh and Sándor Sík.[6] The Alliance of Hungarian Writers, a strongly nationalist group lead by Dezső Szabó, was greeted in a letter by Gárdonyi.[7] Later, even stronger statements followed. ‘Of the numerus clausus law I think it is perfectly justified. Jewish youth took over our universities…Antisemitism is the self-defence of the Hungarian race against the ever-stronger Jewish race, he told a Jewish newspaper in his final months in 1922.[8]

Today, of course, such statements would end someone’s career—back then, these misguided notions were more commonplace. But the Communists were definitely wrong to declare Gárdonyi as one of their own—he was a nationalist, perhaps even too strongly so. On the other hand, nationalists would also be wrong to appropriate Gárdonyi—few authors penned such a devastating critique of the state of the Hungarian language, literature, culture and contemporary etiquette as he did. Gárdonyi was a unique personality, a distinctive Hungarian writer, in both his good qualities and his faults. He cannot be branded or put in a box. He must be seen in the light of what he created, with his insightful criticisms taken to heart, and his failures appropriately assessed.

[1] Új Barázda, 31 Oct. 1922.

[2] Szabad Nép, 27 May 1948.

[3] Csillag, 1 Feb 1952 and Lobogó, 1 Nov 1972.

[4] Pesti Hírlap, 28 March 1920.

[5] Pesti Hírlap, 4 Jan 1920.

[6] Magyarság, 8 Jan 1921.

[7] Egri Népújság, 9 March 1920.

[8] Múlt és Jövő, 28 July 1922.