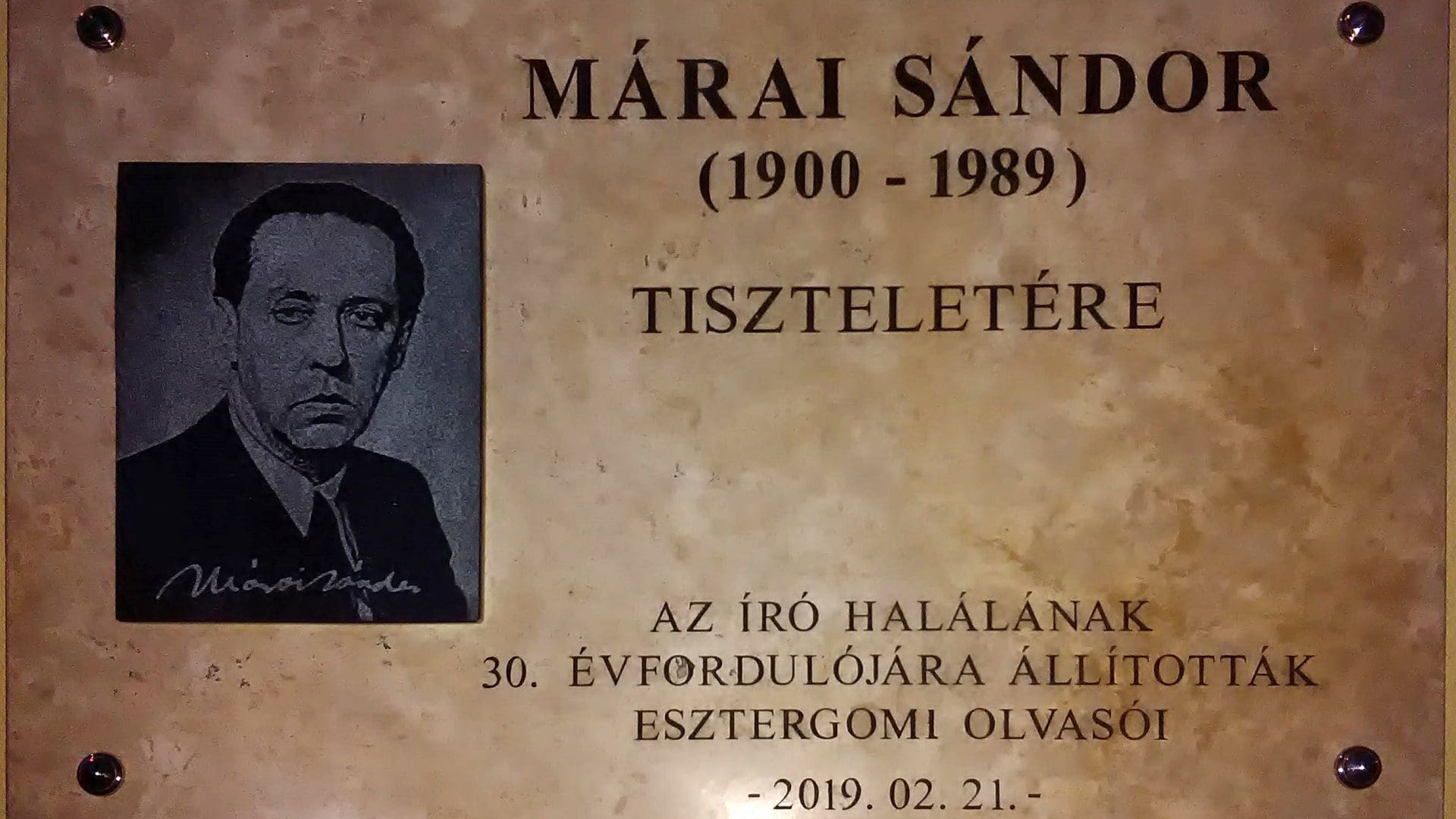

Sándor Márai was born on 11 April 1900, in Kassa, Kingdom of Hungary (which is known as the Slovakian city of Košice today). Márai was educated in the towns of Kassa and Eperjes. His interest in literature was apparent from a very early age. Upon completing secondary school, he enrolled at a university and began his literature studies while also commencing his literary career. Even though he was born into a family of some wealth and got a decent education, the time of his birth at the turn of the century destined his life to be marked by many challenges.

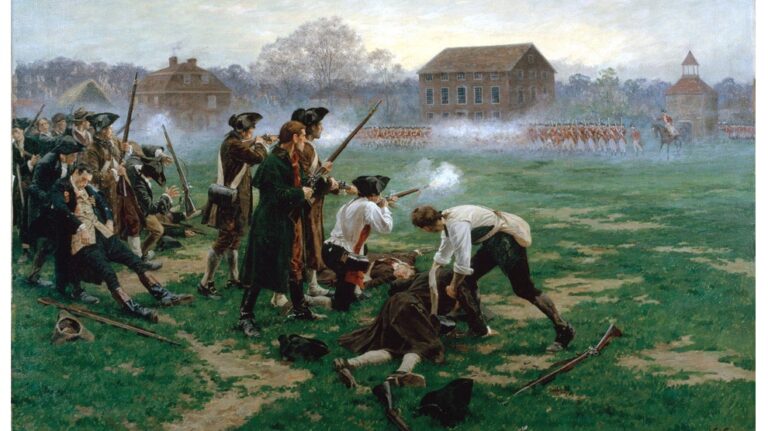

In 1918, Hungary found itself defeated in the First World War. Subsequently, the Treaty of Trianon assigned his hometown under the jurisdiction of the newly formed Czechoslovakia. Despite the peace treaty, conflicts in the region persisted, with battles erupting then between the newly emerged communist Hungary and the new states that had formed on the remnants of the former Astro-Hungarian Empire.

At the dawn of his life, Sándor Márai was supportive of the cause of Hungarian Bolshevism, and therefore endorsed the installation of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, a short-lived Soviet-style communist regime in Hungary between March 1919 and August 1919. After the rule of the Hungarian Bolsheviks, which was marked by the red terror, was crushed, a brutal so-called ‘white terror’ against the Bolsheviks’ supporters ensued.

Given Márai’s association with the Reds, his family believed that it was for the best to leave the country and move to Germany.

Even though Márai had to temporarily part with his homeland, his journalist and writer career began to bloom abroad. He was published in multiple prominent magazines, such as the German Der Drache, Simplicissimus, and Frankfurter Zeitung, his hometown’s Kassai Napló and Kassai Újság, and Czech journals published his works as well. Partially due to his work in journalism, he started to travel around the world, including Europe and the Middle East.

He summarized his experiences in his work titled In the Footsteps of Gods (Istenek nyomában). When the storms settled, he and his wife moved back to Hungary. In 1934, he published Confessions of a Citizen (Egy polgár vallomásai), a reflection on his youth, which has since acquired the distinction of one of his most recognized and enduring masterpieces.

The widespread recognition of his literary work granted him a notable influence as a public intellectual. He took part in the World Peace Congress in Geneva, Switzerland gave lectures on the Hungarian Radio, and wrote for Nyugat, probably the most important literary journal Hungary has ever had. Theatres played spectacles based on his stories, which had incredible popularity and achieved great financial success.

Eventually, the tremendous fame he enjoyed was interrupted by two tragedies.

In 1939, on 28 February, his son, Gábor Kristóf Géza was born. However, within a few weeks, the child died of haemophilia. The author was deeply shaken by the tragedy, which left a huge scar on his heart. Later, he tried to sublimate his feelings in his poem Upon the Death of a Small Child (Egy kisgyermek halálára).

The second trauma that changed Márai’s and so many others’ lives was the Second World War. Márai ardently opposed national socialism and fascism, and used his talent and influence to fight against these horrid ideologies. He also expressed his worry for Hungary and for Europe as a whole, which he dubbed ‘his second homeland’. What added to his worries was that his wife was of Jewish heritage, and while this had not posed a life-threatening issue until the 1940s, the situation took a radical turn when the Germans invaded Hungary. ‘X was deported to Poland’—he wrote following his unsuccessful attempt to release his wife’s father from the ghetto. More to his family’s dismay Márai’s house was entirely destroyed by bombs.

Following the conclusion of the war, he articulated his thoughts and concerns about Hungary’s future in the following way:

‘For now, all that is certain is that Budapest and the other cities will be destroyed, and the national existence of the country is in question if the Russians arrive not on the basis of agreement, but by the right of arms, as victors on a battlefield’.

In the same work of his, he expresses deep dissatisfaction, and disillusionment with the new state of the world, describing the desire to escape the newly built post-war world order. At the same time, he is not devoid of feelings of national pride:

‘If I’m still alive, if I have the strength and the means to leave from here [from Hungary], I will. To write in Hungarian, also abroad, to work for the education of Hungarians. But I’ll leave from here. I don’t hide it: they offended me’.

In 1948, Sándor Márai faced a relentless barrage of attacks by the forming Communist system. The writer, who had bravely opposed fascism, was forced to flee his homeland by the Communists who seized power in the country. As he departed,

he pledged never to return as long as Soviet troops occupied Hungarian soil.

Even his election as a full-fledged member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, one of the few positive events in his life during the war, was rescinded under the influence of the Soviet regime. After his forced emigration, he lived in Switzerland, Italy, and then the USA, eventually becoming an American citizen.

In his exile, Márai was one of the intellectual leaders of Hungarians resisting Communism. He continued to write in Hungarian. His poem titled Funeral Oration (Halotti Beszéd), which was published in 1951, resonated deeply with the hundreds of thousands of Hungarians forced into exile all around the world. Due to this relatability, the poem became the unofficial anthem of all Hungarians who were exiled from their Motherland. He also worked for the American Radio Free Europe for 16 years, from 1951 to 1967. Hungarians, whether residing in their homeland or scattered across the globe, tuned in every Sunday to his radio programme Sunday Letters.

He closely monitored the developments of the 1956 Revolution without interruption and shared his insights on Radio Free Europe, where he was employed. Fuelled by the hope that his homeland would break free from Soviet occupation, he flew to Europe on 6 November, aspiring to witness the unfolding events firsthand. Regrettably, upon his arrival in Munich on 7 November, he was met with the harsh reality that Hungary’s fate had already been decided. During this time, he felt immense disappointment in the Western powers, as they had not extended a helping hand to Hungary when it most needed it.

He mourned the crashed revolution through his poem, The Angel from Heaven (Mennyből az angyal), which he recited on the radio. Today, the poem decorates the 1956 Revolution Monument in Budapest’s 7th district on Rózsák Tere (Roses’ Square):

‘Angel from Heaven, do rush, don’t rest,

Hurry to smouldering Budapest.

Go to where, among the Russian tanks,

The silent bells give no sound of thanks.

Where there’s no Christmas sparkle to please,

Where nuts painted gold don’t hang on trees,

There’s nothing but hunger, shivers, cold,

Do speak so they will grasp what you told.

Split with your voice the night asunder:

Angel, carry news of the wonder’

His illness and a series of personal tragedies, such as the death of his brother and stepson, drove him to commit suicide on 21 February 1989, in the city of San Diego, California where he wrote the last works of his life. It happened just one year before the Communist government of Hungary was ousted and two years before the last Soviet soldier left the country. Thereby, he fulfilled his oath never to return to his homeland until it was communist-occupied.

Just a few months following his passing,

Márai was posthumously venerated with Hungary’s most prestigious literary honour, the Kossuth Prize, and his membership was reinstated in the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

In the new Hungary, his works became the symbol of new hope, and his literary fame soon spread to the rest of the world as well. His works have been translated into several languages, including Czech, Spanish, Finnish, Swedish, English, Italian, German, French and many others too. His 1942 novel, Embers (A gyetyák csonkig égnek), a captivating story about two men, once best friends, meeting after more than 40 years without seeing each other, has become an international bestseller.

Related articles: