This article was originally published in Vol. 5 No. 3 of our print edition.

In February, Adrien Brody took home the Oscar for Best Actor for his portrayal of a Hungarian architect rebuilding his life after the Holocaust. The film in which he starred, The Brutalist, also took home the Best Screenplay gong. With its three-and-a-half-hour running time, its harking back to the Hollywood epic, its ‘immigrant story’ basis, and dazzling 70 mm cinematography provided by Laurie Crawley, The Brutalist was a monumental slab of Oscar bait. A film of an ambition that Hollywood seemed to have mislaid in recent years.

It tracks one man, László Tóth, as he leaves Hungary in the aftermath of the Holocaust to rebuild his life in the United States. Tóth is an architect who wants to remake human consciousness in a new, purified form: Brutalism. The metric tonnes of concrete he pours upon the landscape of his adopted country are meant to be monumental. Here is the artist of genius, portrayed with a purity that calls to mind the work of a fellow Eastern European émigré in Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. For an ultra-modest budget of $11 million,1 the crew managed to give a satisfactory impression of Tóth’s architectural masterpiece: a community centre comprising a library, theatre, gymnasium, and chapel, commissioned by a philanthropist in tribute to his mother. In fact, production designer Becker used several real brutalist buildings in and around Budapest2 to stand in for Tóth’s creation. Brody also has a Hungarian grandfather, who left after the Revolution of 1956,3 so the story is not simply incidentally Hungarian.

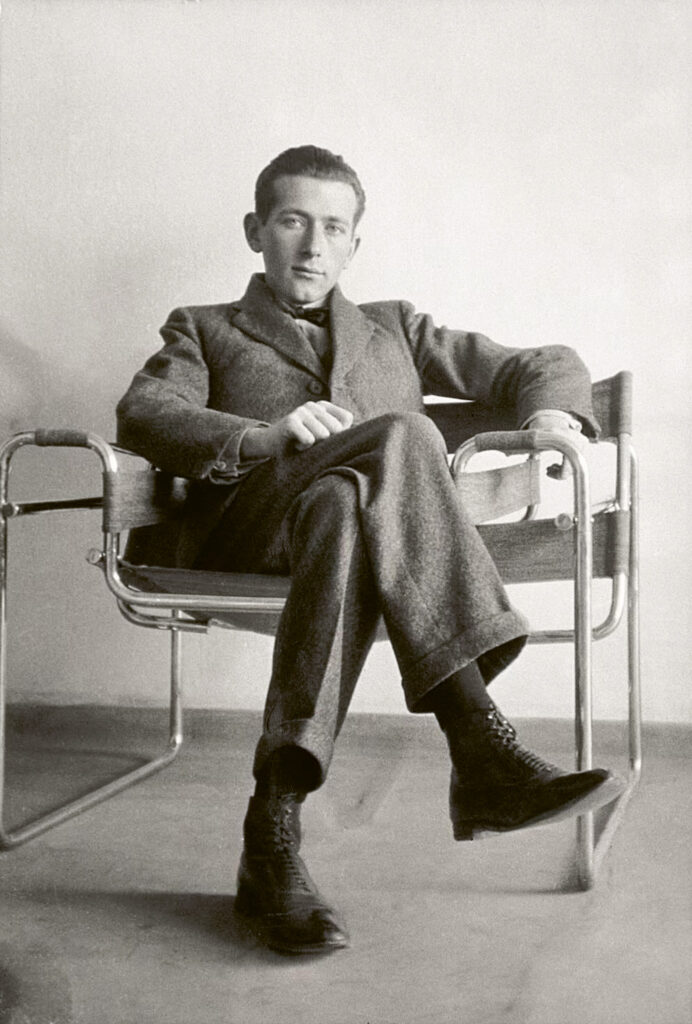

Moreover, despite its aspirations of grandeur, it is a story that also rings true. Audiences left cinemas yearning to know more about the life and works of this great Hungarian American, only to be disappointed to discover that he does not exist. There are at least three men who could fit the bill, though. The first, most brilliant, and most timely would have to be Marcel Lajos Breuer. Like Tóth, Breuer was a Jew, born in Pécs in 1902, which would have put him in his thirties by the advent of war.4 Like Tóth, Breuer was a truly brilliant figure who poured into his architecture a desire to remake the way we see the world. In this, he succeeded at perhaps three different points. At eighteen, Breuer moved to Germany and joined the Bauhaus school.5 There, he immediately came under the spell of Walter Gropius. Gropius was the founder and visionary behind much of what we today call Modernism. He believed in straight lines, simplicity, form following function, and mood following material. Immediately, Gropius identified his new pupil as of a different class. A year later, Breuer was elevated to run the Bauhaus woodwork school, where he soon became friends with the pivotal abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky.6

It was in his furniture-making guise that Breuer performed his first twentieth-century revolution—the Wassily chair, named after his friend. A keen cyclist, Breuer had become obsessed with the steel tubing that had become prevalent in bicycle manufacture. He wondered if the same technique could be applied to the manufacture of furniture. The result was a chair wherein fabric sections were strung across a steel tube frame, a system that seems instantly familiar to us today, but at the time was unheard of. A few years later, Breuer left to form his own architectural practice in Berlin, supported initially by royalties from the Wassily chair. And it was in Berlin that Breuer was forced to renounce his Judaism in order to marry his wife, Martha Erps. As the situation of Europe’s Jewry became ever more difficult, in 1935, on Gropius’s advice, Breuer relocated to London, where he lived in the modernist masterpiece apartment block Isokon, in Hampstead, alongside both Gropius and a fellow Hungarian architect, Ernő Goldfinger.7

After the war, Gropius headed to Harvard, and Breuer went with him, working in Gropius’s Graduate School of Design. Here, he began picking up commissions for houses and pioneered perhaps his second social revolution, the ‘wing’ style, as exemplified by his Geller House, Connecticut.8 In this ‘machine for living’, the roles of family life were cleaved into separate ends of the same building. The children had their wing, while the adults—as well as general common areas like the kitchen and living rooms—were the other side of a central entranceway and lobby, across a single floor, so that the finished building gave something of the effect of a bird’s wings. Furiously productive, Breuer gradually came by larger and larger commissions. In 1955, this climaxed when he was chosen to build the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. The reviews at the time were glowing. Today, a bit like the Wassily chair, it merely looks like one among many. Glass and concrete, with columns lifting the building above the ground, creating open spaces below, and a Y-shaped plan ‘symbolizing openness and inclusivity’, many of these features became tropes to a later generation of architects, making this structure a victim of its own success.

‘Audiences left cinemas yearning to know more about the life and works of this great Hungarian-American, only to be disappointed to discover that he does not exist’

In 1977, he created the Hubert H. Humphrey Building, which serves as the headquarters of the US Department of Health and Human Services, located at the foot of Capitol Hill. The lobby is paved with travertine, a form of limestone deposited by mineral springs, and it originally held two tapestries designed by Breuer himself.9 Like the best of Brutalism, despite the concrete, it is by no means cheap or gaudy. There is even a pious quality to its studded reproduction: small windows, girded with warm yellowish concrete, opening onto a wide, almost Spanish plaza. It is both a personal and aesthetic advance from the UNESCO headquarters, but times were already changing, and Breuer, who had always been carried forward on history’s currents, found himself caught in its riptide. By the mid-1970s, the promise of Le Corbusier’s system had turned into a world of filthy social housing estates, inhuman office blocks, draughty ‘walkways in the sky’ and tone-deaf monuments. To the public, the Hubert H. Humphrey was just one more of those. The Humphrey Building was resented then and remains resented today.

Fashion is a cruel mistress. Perhaps it is inevitable, then, that the most lasting of his buildings would end up being his churches. Saint John’s Abbey Church, in Collegeville, Minnesota, was completed in 1961. Designed for the Benedictine monks of Saint John’s Abbey and University,10 it is brutalism at its most brutal: the entire structure is constructed from béton brut, and its facade is dominated by a massive bell-banner, centred around a cross-shaped void that houses the church bells. Meanwhile, the interior is centred around vast, open spaces, with natural light entering through geometric patterns of coloured glass. Five years later and not so far away, the Saint Francis de Sales Church in Norton Shores, Michigan, offered a towering central box of a concrete nave, topped by a structure that resembles a steel railway girder. Both buildings have a quality of sails—long, wide slabs of concrete that open their arms wide to the passing traveller. They have both the movement that brutalists promised and a sense of permanence. After all, the Romans built the Pantheon in concrete; used wisely, it is as sacred as any other material.

Breuer went on to build the Whitney Art Museum, an inverse staircase of a magic box with few windows, at 954 Madison Avenue in New York. The Whitney has moved to a new venue, designed by the starchitect, but the building itself now houses an annexe of the Met, and the space has been rechristened the Met Breuer. With some hilarity, his first American building, the Geller House, was demolished overnight in 2022, to make way for a tennis court. America does not always display the same architecture-worship as Europe.

A man whose life closely paralleled that of Breuer was our second candidate, who comes with the right first name: László Moholy-Nagy. Jewish, Bauhaus, émigré in London and then the United States. Weisz ditched his original surname, considering it too semitic. He borrowed ‘Moholy’ from Mohol, a town where he had spent part of his youth, and slapped on ‘Nagy’ (big) as a flourish. In 1914, he was studying law in Budapest when war broke out. He enlisted and served out his time sketching on postcards before being injured on the Russian front—evidently something of a million-dollar wound. After the war, he abandoned his studies for art school.

In 1926, he created Ein Lichtspiel: Schwarz Weiss Grau (A Lightplay: Black White Grey). This was the first great act in a life obsessed not so much by architecture as something more rarefied—interplay, the spaces between shapes. Design in its purest form. Ein Lichtspiel had no plot, but featured a device he dubbed ‘the Light-Space Modulator’: shiny metal discs, spinning wheels, rods, and perforated shapes. A technique of light-refraction that will be familiar to fans of modern music videos, but at the time seemed revolutionary.

Moholy-Nagy was what would come to be known as a Constructivist. His art is often straight as a die. Crisp, colourful, abstract lines and shapes, always rushing forward into the piston future. As the Nazis rose, he first found himself in London, alongside Goldfinger. The pair were both part of the same Hungarian clique centred around the Hampstead Isokon Building. Gropius and Moholy-Nagy tried to start a British version of Bauhaus, but alas, never secured funding.11

Life in London was hard and scrappy. He scraped by with commercial jobs, having been turned down for a teaching post at the Royal College of Art. He worked on campaigns for Imperial Airways and shop displays of men’s underwear—often alongside the New Bauhaus theorist and fellow Hungarian György Kepes. He photographed architecture for Architectural Review, where the assistant editor was the poet and architecture critic John Betjeman. By 1936, he had designed the special effects for the classic H. G. Wells film adaptation Things to Come. An honour perhaps only pipped by being included in the Nazi Party’s infamous Degenerate Art exhibition the following year. That was also the moment at which he emigrated again, to the United States, following Gropius out to Chicago, where he became director of the New Bauhaus school. By 1949, his School of Design in Chicago had become the first institution in the United States to offer a PhD in the subject.

Moholy-Nagy died young: cancer took him at 52. But his crisp, organic vision lives on. ‘Designing is not a profession but an attitude’, he famously said. A motto that could be taken up by Jonathan Ives or Frank Lloyd Wright. His book Vision in Motion (1947) is part manifesto, part cosmic design sermon.

The final candidate for the true Tóth must be Ernő Goldfinger. Also a Jew, and born in almost the same year, like Breuer Goldfinger soon escaped Hungary to study at a salon in Paris, then went to London to pursue his career, and immediately became embroiled in a lawsuit after his first major client refused to pay the bill, claiming that the building he had erected was ‘too modern’.12 Despite this setback, however, Goldfinger had luck on his side. Unlike Tóth’s hardscrabble efforts to scrape a living, by the 1930s Goldfinger was married to the heiress of the major food conglomerate Crosse & Blackwell. He and his wife relocated to the plush suburb of Hampstead, where they set about building their home, 2 Willow Road.13 This was to be a modernist’s manifesto. A row of workers’ cottages had to be knocked down to create its angular two-storey structure, an act that immediately drew the ire of a former Royal Navy intelligence officer and sometime author, Ian Fleming, who happened to live down the road. So peeved was the always annoyed Fleming that he named the baddie in one of his 007 novels after Goldfinger.14 The house is today a museum to his career.

However, it was not until after the Second World War that Goldfinger achieved the kind of monumentalism that he craved, with Balfron Tower in Poplar and Trellick Tower in Notting Hill. Ten miles apart, but twins in style and size, with their distinctive separated lift towers, these two great grey concrete stacks together form a giant set of wickets across the cricket pitch of Central London. Inspired by Le Corbusier, Goldfinger had long been banging the drum for a new form of social housing, one that he felt could sanitize and civilize the grim East End.

His entreaties caught the ear of what would become the Greater London Council, which gave permission for his 30-storey Balfron Tower. Goldfinger famously lived in the penthouse atop it for the first year of its life, and held fabulous Saturday night parties to which he invited the other tenants, asking them to talk to him about how they found it—what they enjoyed, what worked, and what did not.15 These insights were rolled into its sequel, Trellick, in the once similarly deprived Notting Hill. But they did not work. Trellick became a byword for ugliness—Britain’s most hated building in several polls. And it became a sink estate. Malfunctioning lifts lead to long journeys up and down the stairs. After a gang of vandals let off a hydrant, residents spent four days over Christmas without electricity. Other vagrants would regularly toss bottles and furniture from higher floors onto a central plaza, giving those arriving the impression of being shelled.16

Today, both Balfron and Trellick have found redemption, via canny residents’ associations, mass refurbishment programmes, and the way the ever-inflating London property bubble has pushed out the more undesirable sort. In modern London, both are now filled with Crispins and Octavias, architects and graphic designers who want a home that complements their G-Plan furniture; modish modern people in thrall to Brutalism. Indeed, these two are sites of pilgrimage, opened up to ordinary folk every year for the Open House London festival of architecture. Yet despite their recent redemption, they remain somewhat unlovable. As pieces of conceptual theatre, Goldfinger’s works still have the power to spike the adrenal glands. And of course, once inside, the features and fittings are of a comforting standard. But as art, at a human scale, they are impositions. Two middle fingers, swivelled towards a London that once was, before the mid-century planners intervened.

In that sense, Brody’s Tóth represents both the best and worst of the Brutalist and Modernist traditions: at its best, revolutionary aspiration, a desire to comfort humanity. At its worst, the triumph of theory over feeling, and of the ego of the starchitect over the lives of the termites who toil in his mounds.

All three find themselves balanced precariously on the edge of forever. Men whose lives sought to overturn the comforts we feel organically, in order to grasp at a new kind of comfort, morally uplifting to a New Man. They are supremely 20th-century figures. And that is what The Brutalist seems to want to talk about, and why it is a great film. It drinks in the full sweep of the ‘short twentieth century’: a time where we let go of our desire paths, and drew straight lines. Both the most morally improving and inhuman of ages. A time of wild seriousness, huge dreams, and base literalism as a credo. It is exactly what the life of Tóth—and his flight from Nazi-ravaged Europe—seems to represent.

NOTES

1 Alec Nevala-Lee, ‘Brutalist: A24 Movie Oscars 2024 Budget & Release Date’, Slate (20 December 2024), www.slate.com/culture/2024/12/brutalist-a24-movie-oscars-2024-budget-release-date.html.

2 Thomas Page, ‘The Brutalist: Adrien Brody, Judy Becker Interview’, CNN Style (19 December 2024), edition.cnn.com/2024/12/19/style/the-brutalist-adrien-brody-judy-becker-interview/index.html, accessed 29 Apr. 2025.

3 ‘Brutalist Film Wins at Oscars’, BBC News (10 March 2025), www.bbc.com/news/articles/cm21jyqn6y7o.

4 ‘Marcel Breuer Papers, Biographical Note’, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, www.aaa.si.edu/collections/marcel-breuer-papers-5596/biographical-note, accessed 29 April 2025.

5 ‘Marcel Breuer Papers, Biographical Note’.

6 ‘The Met Collection: Marcel Breuer’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/485067, accessed 29 April 2025.

7 ‘Feature Review’, The Guardian (17 January 1999), www.theguardian.com/theobserver/1999/jan/17/featuresreview.review1, accessed 29 April 2025.

8 James S. Russell, ‘Though Beloved, Midcentury Modern Houses Are Vanishing’, Architectural Record (20 February 2022), www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/15520-though-beloved-midcentury-modern-houses-are-vanishing.

9 Sarah Booth Conroy, ‘Marcel Breuer: The Man, the Myth, the Craft’, The Washington Post (5 November 1977).

10 ‘St John’s Abbey Church in Collegeville’, Liturgical Arts Journal (September 2023), www.liturgicalartsjournal.com/2023/09/st-johns-abbey-church-in-collegeville.htm.

11 ‘Bauhaus in Belsize Park’, The Art Newspaper (9 July 2018), www.theartnewspaper.com/2018/07/09/bauhaus-in-belsize-park-gropius-breuer-and-moholy-nagy-honoured-in-london.

12 Gillian Darley, ‘Don’t Teach Me’, London Review of Books (26 July 2007), www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v26/n07/gillian-darley/don-t-teach-me.

13 Darley, ‘Don’t Teach Me’.

14 ‘Hay Festival 2005 Coverage’, The Guardian (3 June 2005), www.theguardian.co.uk/2005/jun/03/film.hayfestival2005.

15 Darley, ‘Don’t Teach Me’.

16 ‘Trellick Tower: History and Ballad’, The Telegraph, www.telegraph.co.uk/film/high-rise/trellick-tower-history-ig-ballad/, accessed 29 April 2025.

Related articles: