Dr Zalán Bognár is the president of the International Association of GUPVI/GULAG researchers, and associate professor of the Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary, and a leading expert in Hungary in the history of the Hungarian forced labourers and prisoners of war. He spoke to Dániel Farkas, a senior researcher of the Danube Institute, on the occasion of the Memorial Day of Hungarian Political Prisoners and Forced Labourers in the Soviet Union, commemorated on 25 November since 2012.

***

Why 25 November? Why is this day special in the history of the forced labourers and political prisoners taken to the Soviet Union?

This is the day when the first political prisoners arrived back in Hungary following the amnesty after the death of Stalin. This is why it was chosen as a day of commemoration. Curiously, this was also the day of the match of the century, when Hungary defeated England 6–3 in the famous soccer match. Another interesting coincidence: Marina Gera, the lead actress of the movie Eternal Winter, which is about the experiences of Hungarians in the Soviet prison system, received an Emmy for her acting on this very day in 2019.

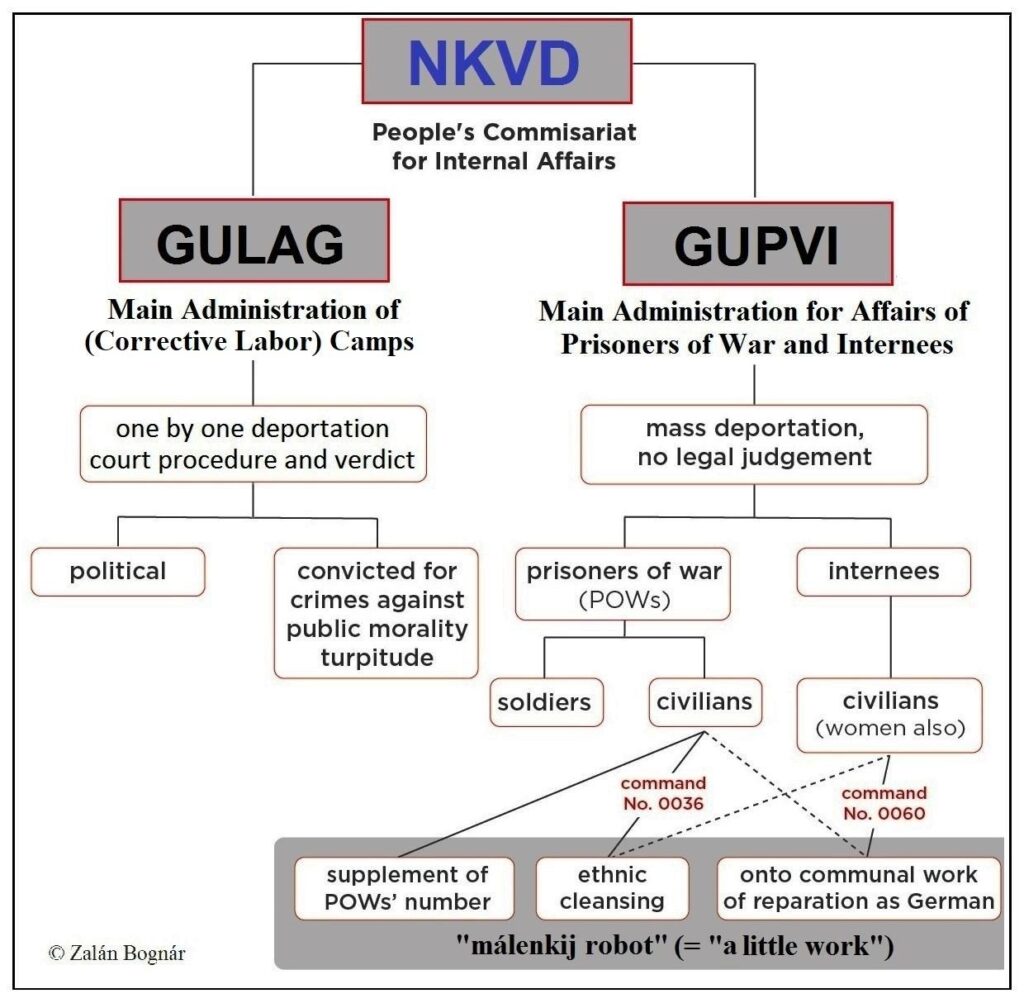

The name of the scientific association that you lead distinguishes the GULAG and the GUPVI camps in the Soviet prison systems. What were the differences between these?

In short, the GULAG was a system for political prisoners and common criminals with judicial sentences, while the GUPVI was for POWs and deportees in connection with the Second World War. GULAG is an acronym for Glavnoye upravleniye ispravitel’no-trudovykh lagerey, which translates to Main Directorate of Correctional Labour Camps.

The GULAG system was opened in 1934, although obviously, there were labour camps and penal colonies well before that. The last ones that were in European Russia were evacuated beyond the Urals after the German invasion started in 1941. In the case of the GUPVI, it is the Russian acronym for Glavnoye upravleniye po delam voennoplennykh i internirovannykh, that is, Main Administration for Affairs of Prisoners of War and Internees. These camps were created after the Nazis and the Soviets jointly invaded Poland in September 1939, initially to house Polish prisoners. Then it was extended to other prisoners who were captured during the war. It is important to note that these were not all soldier prisoners.

In the case of Hungary, a million people passed through GUPVI camps from a country of 14,7 million. Two-thirds of them were soldiers, and one-third were just civilians. The camps for POWs were actually better than the ones for internees. And nobody in these camps received a judicial sentence. They were just rounded up by the Soviet Army and taken away for forced labour.

That is a lot of people. What was the logic behind sending civilians to prison camps without sentences? Was it an economic motive, similar to slavery in earlier times?

Some people are stressing that it was an economic necessity for the Soviets to run labour camps with foreign prisoners. I think for the GULAG camps, the main point was terror. Old and frail people, even the disabled, were taken away to the camps—obviously, there is no economic sense in that.

We know from the recollections of victims that Soviet guards sometimes expressly told them that they were there to work until they died. Obviously, the camps still contributed to the Soviet economy, especially in mining. This is why they took so many people to GUPVI camps—they just needed the labour force.

‘They were there to work until they died’

Most of the GUPVI camps where Hungarians were taken were in the Donbas, where the war rages now, where they worked in coal mining. The GULAG camps represented around 1–2 per cent of Soviet GDP in the late 1930s.

So, when did these deportations commence and when did they end?

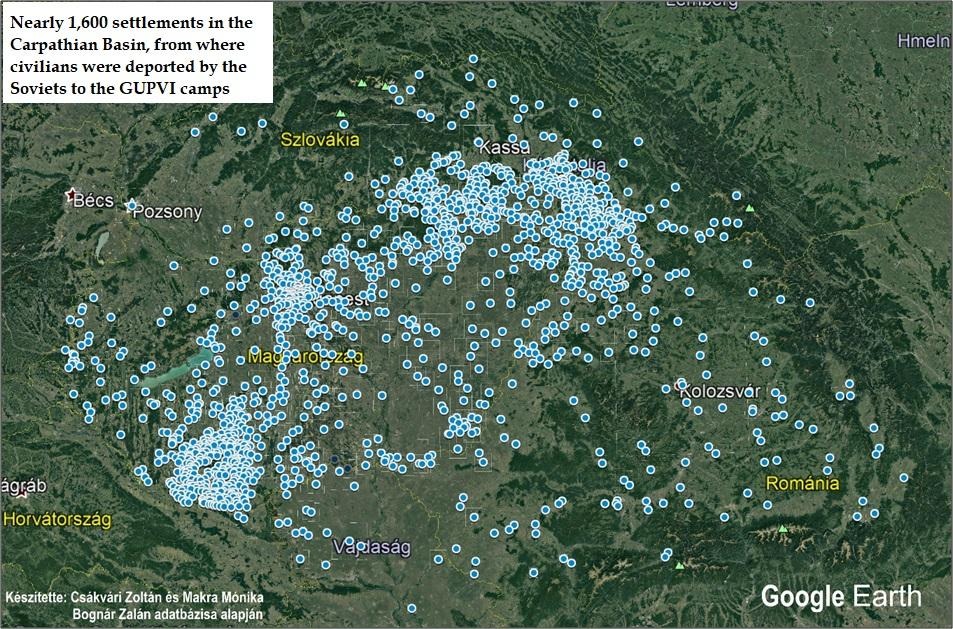

The first deportations commenced in Székelyföld [Szeklerland] in September 1944—we count it among the Hungarian territories because it was under Hungarian administration at the time of Soviet invasion at the end of August.

The last ones that I found were on 30 May, from Somogy county. It is important to note that by that time, the guns were silent in Europe for three weeks, and the Soviets were still taking people away into prison camps.

They were originally after soldiers, but they counted everybody who received military training as a soldier. So it was all adult males. Even kids between the ages of 12–16 received some kind of military education in the Levente system. Because of that, they were threatened by captivity as well, and a lot of them were taken into GUPVI camps.

Were there regions in which this terror especially impacted?

As for the special impact, there were three regions, really. The first was Kárpátalja, the present-day Zakarpattia region of Ukraine. The point there was ethnic cleansing. In November 1944, the Soviets were already preparing to annex the territory, which had belonged to Czechoslovakia until its breakup in 1939, when it was reannexed by Hungary.

So they rounded up local Germans and Hungarian males, a week before the Communist Party congress of Zakarpattia, where the Soviets announced the accession of the territory to Soviet Ukraine. They did not want any trouble.

Most of these people died on their way to the camps, because they were taken in late November with just the clothes on their backs. Typhoid, hunger and exposure were taking their toll.

It is well measurable from the documentation. Hungary purchased nearly 700,000 files of prisoners inside the Russian Federation. Only 21 per cent of the Hungarians taken from Beregszász in that November were found among them. The explanation? The camps registered only those people who arrived, sometimes just weeks after their arrival. If one died en route or before registration in the camp, you were not counted.

So you can see—it is likely that almost 80 per cent of the deportees from Beregszász died on their way to the camps.

The second region especially impacted was Budapest. On 27 October, Stalin ordered the Soviet 2nd Ukrainian Front (army group), which was then standing in Bács–Kiskun County to the South, to take Budapest. Its commander, Malinovsky, pushed back because his forces were depleted, but Stalin ordered the attack anyway.

The offensive consequently was a failure—it got stuck in the southern suburbs of the capital. The joint effort of the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts was needed to take the city in a prolonged siege by 13 February. The Soviet generals needed to explain their failure, so they announced that between 180,000 and 200,000 Germans and Hungarians were defending the city. The real number was around 80,000.

Thus, in order to make up for the shortage of prisoners of war, the Soviets took around more than 100,000 civilians as ‘prisoners of war’ to materialize these made-up Nazi hosts.

My grandfather was also arrested on the street a month after the siege ended, along with several other civilians.

The third region of focus was the Southern Transdanubia. It was because of its ethnic makeup. Stalin ordered on 16 December 1944, that all ethnic Germans in ‘liberated’ territories should be deported. Southern Transdanubia is home to the Schwabs, an ethnic German group settled in the 18th century. It was announced that all males aged 18–45 and females aged 18–30 were to report for two weeks of work. And then they were put in camps for years.

It is also important to note that these categories were not clear-cut. The Soviets wanted just a certain number of prisoners based on their target figures set by their leadership. So if they thought there were not enough Germans deported, they just took the neighbouring ethnic Hungarian village as well. When somebody escaped, the number was made up by anybody they could catch on the street.

There was an instance when a group of military prisoners realized in a Romanian train station that they were being deported, and so jumped off the carriage and escaped. They simply pushed a couple of Romanian railway workers among the prisoners. I myself see single files where the date of captivity is noted as summer 1945. They are curious, because there are only 1–2 people with such dates, but it is clear that they were captured to make up for escapees.

The whole system was evil and irrational. An observer noted that there was a full company of French soldiers in a transit camp. They escaped from German captivity, hid in Hungary, but they were put among the forced labourers simply because the Soviets wanted more people in the camps.

How did you find this topic to research?

I started to work in the Archive of Military History precisely in 1990, the year when Hungary transitioned to democracy. I was responsible for the most recent post-1945 papers. And there I found no less than 347 boxes that dealt with the issue of prisoners-of-war and other deportees in the Soviet Union.

And there it struck me the old family story, which made no sense at first glance: my grandfather, Pál Petőváry, was taken away from the streets of Budapest as a civilian a full month after the capitulation of the city. He returned years later, weighing just 38 kilograms—he was 85 kilograms when he was taken away.

‘I need to continue, to bring these stories to light’

I found his name in the list of prisoners, opened the file, and found my grandmother’s letters pleading for the release of her husband, the father of her children. And so I was looking at these boxes and realized that I now have 347 boxes full of these stories.

So I started to work, and never stopped since then. I faced some pushback from time to time. But I need to continue, to bring these stories to light, not least to bring justice to the victims.

Related articles: