The article is a product of the project titled Conservative Case in Education, supported by the Mathias Corvinus Collegium Learning Institute.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Hungary faced an epoch-making situation. After the Treaty of Trianon, the country suffered enormous territorial losses, leading to national discontent and an uncertain future. Gyula Kornis, a former Piarist monk, philosopher, and statesman, emerged from this troubled period and would play a critical role in promoting a vision for Hungarian education to enhance national identity, culture, and moral values.[1] While he is recognized for his contributions to conservative educational policy, the evaluation of his activities remains a topic of ongoing debate, highlighting the complexities of interwar Hungarian intellectual life.

Early Life and Academic Ascendancy

Born on 22 December 1885 in Vác, Hungary, Gyula Kornis had an early life marked by hardship following his father’s premature death. Raised in modest circumstances, Kornis joined the Piarist order, which allowed him to pursue higher education at the University of Budapest, where he completed his studies in Hungarian and Latin. Mentored by philosophers such as Frigyes Medveczky and Ákos Pauler, Kornis’s academic interests soon extended beyond theology to encompass psychology and pedagogy, reflecting a growing commitment to understanding human nature and moral philosophy.[2] His first scholarly work, The Development of the Hungarian Language of Philosophy (1907), explored the evolution of Hungarian philosophical terminology, an early indicator of his interest in aligning education with national culture.[3]

Kornis’s career began with a teaching position at the newly founded Royal Elizabeth University in Pozsony (now Bratislava), where he was subsequently appointed dean. Following the Treaty of Trianon, which resulted in Hungary’s significant territorial losses, the Royal Elizabeth University relocated to Pécs, and Kornis continued his work there. He later took up a position at Pázmány Péter Catholic University in Budapest, where he again served as rector. His scholarly pursuits during this time focused on idealist philosophy, emphasizing ethical principles and the importance of intellectual growth in shaping societal values. This philosophical foundation would later inform his vision for Hungary’s educational system.

‘Kornis’s educational philosophy was deeply rooted in Hungary’s intellectual tradition’

Philosophical Orientation and Early Ideals

Kornis’s educational philosophy was deeply rooted in Hungary’s intellectual tradition, drawing inspiration from the idealist movements that had permeated Hungarian academia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He viewed pedagogy as a form of applied philosophy that imparted knowledge and cultivated moral character aligned with Christian ethics and national values. Kornis believed that education should serve as a cornerstone of cultural preservation and national identity, a view that resonated with Hungary’s interwar climate of renewal. His academic writings from the 1910s and early 1920s, shaped by idealist principles, laid the groundwork for the extensive educational reforms he would champion later in his career.[4]

Cultivating National Identity through Educational Reform

In the 1920s, Kornis took on a prominent role in Hungary’s educational and cultural policy under the patronage of Kuno Klebelsberg, the influential Minister of Culture. Appointed as state secretary, Kornis was instrumental in implementing Klebelsberg’s vision of a robust national education system that emphasized Christian and patriotic values. Working with Klebelsberg, Kornis helped design a series of reforms aimed at revitalizing Hungary’s education system, with a particular focus on expanding access to quality education in rural areas. This was in response to Kornis’s belief that Hungary’s youth should be imbued with a strong sense of national identity, which he viewed as crucial for the nation’s resilience in a post-Trianon landscape.[5]

One of Kornis’s key contributions was his emphasis on strengthening secondary education and teacher training, ensuring that Hungarian educators were equipped to instil both knowledge and values in their students. He saw schools as more than institutions of learning; they were centres for nurturing a moral and intellectual elite that would safeguard Hungary’s cultural and ethical heritage. Kornis’s approach to education reform reflected his belief that the state had a moral obligation to cultivate civic virtues and a sense of community among its citizens. His influence extended to the establishment of rural schools, which sought to bridge the educational divide between urban and rural Hungary, thereby strengthening national cohesion.

‘He saw schools as more than institutions of learning; they were centres for nurturing a moral and intellectual elite’

Through these reforms, Kornis’s work emphasized that education should be holistic, cultivating both the intellect and character of young Hungarians. This emphasis on ethical and communal values echoed throughout Klebelsberg’s cultural programme and underscored Kornis’s belief that a unified, educated citizenry was vital to Hungary’s future.[6]

Political and Academic Downfall

While Kornis’s conservative ideals aligned with the interwar period’s nationalistic tendencies, his fortunes shifted dramatically following World War II. With the advent of the communist regime, Kornis’s academic and political influence rapidly declined. The new government, hostile to his Christian-national philosophy, stripped him of his positions and dismissed him from public life. In 1945 Kornis briefly served as president of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, but political pressure soon forced his resignation.[7]

In 1951 Kornis was subjected to internal exile in Poroszló, a small town far from the intellectual circles he had once led. His Budapest villa and personal library, which survived the war, were confiscated, leaving him in obscurity and financial hardship. Later, in 1953, the conditions of his exile were somewhat relaxed, allowing him to move to Hajdúszoboszló, where he lived in relative isolation until his death in 1958. His funeral, attended by only a handful of mourners, symbolized the extent of his fall from prominence. Somos Róbert’s comprehensive biography of Kornis offers further details on the hardships he endured during this time, underscoring the political and personal toll of his downfall.[8]

Controversial Aspects and Legacy

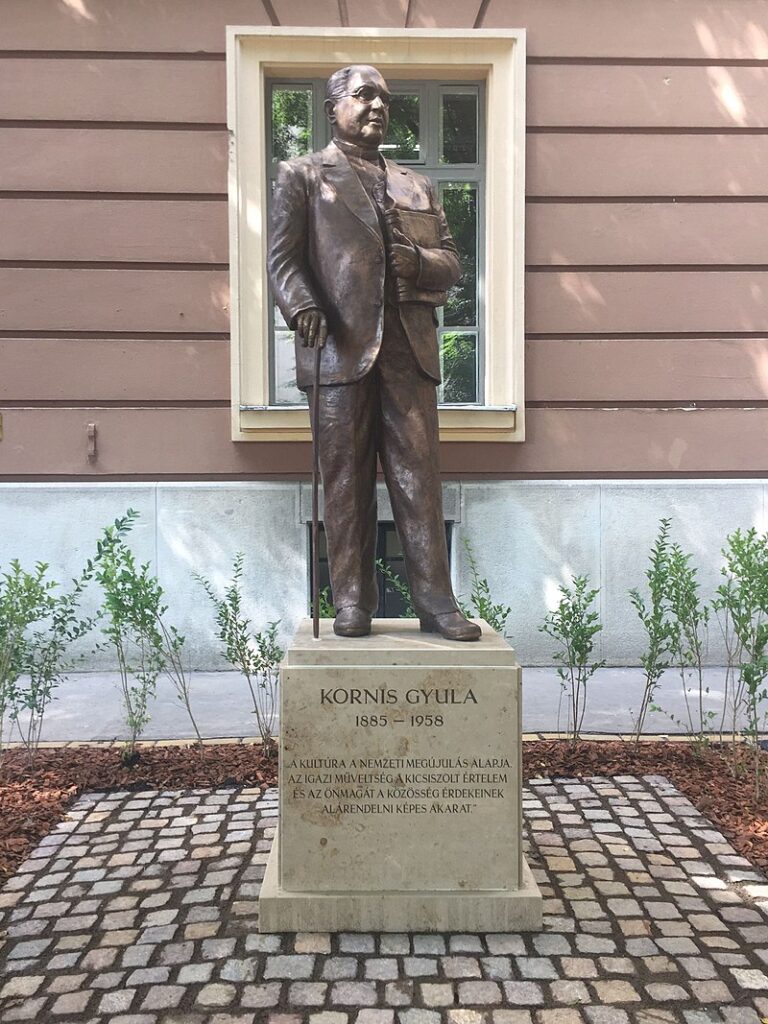

Kornis’s legacy is complex and often contentious. While he is remembered for his unwavering commitment to Hungary’s educational development, his life’s work also reveals a more controversial side. In his writings, Kornis occasionally expressed critical views about the Jewish intelligentsia in Hungary, reflecting the antisemitic undercurrents that were prevalent in certain conservative circles of his time. These views, though not unique to Kornis, cast a shadow over his otherwise significant contributions to Hungarian education and culture. Critics argue that such sentiments detract from his legacy, while some supporters highlight his resistance to totalitarian ideologies and his protection of Jewish students during his tenure as rector. Today, Kornis’s contributions to Hungarian education continue to be recognized, but his legacy remains subject to ongoing debate. His role in establishing a Christian-national educational framework in Hungary is celebrated by some as a defence of national values, while others view his ideological stances as symptomatic of the period’s exclusionary tendencies. Public monuments, such as those erected in Székesfehérvár (2014) and Vác (2019), honour Kornis’s contributions, yet these commemorations have sparked renewed discussions about the nuances of his legacy.[9] His life’s work embodies the dualities of interwar Hungarian conservatism, reflecting both the aspirations and limitations of a society in flux.

[1] Róbert Somos, Kornis Gyula, a filozófus és politikus, Budapest, Kairosz Kiadó, 2019, 85.

[2] József Nagy, Kornis Gyula mint kultúrpolitikus, Budapest, Eggenberger, 1928, 4.

[3] Róbert Somos, Kornis Gyula tudományfilozófiája, Történelmi Szemle, 2020, 301–326.

[4] Péter Agárdi, Nemzeti értékviták és kultúrafelfogások 1847–2014, Budapest, Napvilág Kiadó, 2015, 57–60.

[5] Somos, Kornis Gyula, a filozófus és politikus, 133–168.

[6] Somos, Kornis Gyula, a filozófus és politikus, 176–201.

[7] Somos, Kornis Gyula, a filozófus és politikus, 232–235.

[8] Somos, Kornis Gyula, a filozófus és politikus, 236–237.

[9] László, L Simon, Klebelsberg-Kornis-Hóman — A két világháború közötti kultúrpolitikusok székesfehérvári szobrai, Székesfehérvár, Ráció, 2021.

Related articles: