This article was published in Vol. 4 No. 2 of our print edition.

Introduction

Demography and geopolitics have always been inseparable. Alongside its geographical location and economic power, the population of a country is one of the main factors that determine what military capabilities it is able to develop. The demographic shift occurring at present seems to be becoming a major game changer in this respect. The relative demographic decline of the West, as well as of East Asia and Russia, the slowdown of growth in South and Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean, combined with the demographic explosion of sub-Saharan Africa, will most likely transform the global demographic balance to an extent that will also significantly impact geopolitics.

Global Trends

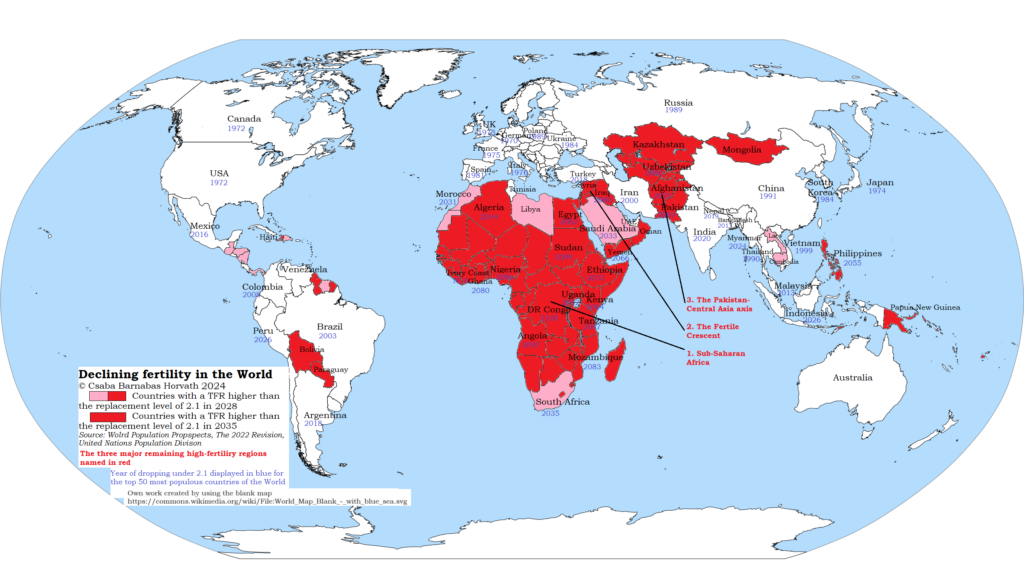

As shown on Map 1, global population trends are reaching a phase where the total fertility rate is dropping below the 2.1 replacement rate virtually everywhere except for Africa and much of the Muslim world, approximately the region that has been known since the early 2000s as the Greater Middle East.1 By 2028, there will only be one non-African, non-Muslim-majority country above 30 million people with a total fertility rate higher than 2.1, the Philippines. Thus, the pattern we became familiar with throughout the second half of the twentieth century, characterized by low fertility rates in the global North and high fertility rates in the global South, is giving way to a new one, seemingly characterized by high fertility rates in Africa and the Greater Middle East and low fertility rates everywhere else.2

The regions shifting from the high fertility rate group to the low fertility rate group include Asia outside the Greater Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean. This means that in terms of demography, these regions will soon find themselves in the same situation as the global North, and at variance with Africa and the Greater Middle East. Demographic decline has long been expected in China, of course, with its one-child policy having been in effect for more than three decades (1980–2016). However, the shift goes much further than that. Countries that have long been seen as unalterably characterized by extremely high fertility rates and population growth, and as inexhaustible sources of migration, such as Mexico in Latin America, or India and Bangladesh in Asia, may in a generation’s time turn into societies characterized by demographic stagnation, becoming acquainted with the issue of aging, and possibly even facing immigration pressure from Africa and the Greater Middle East themselves. This even raises the question of whether this, combined with the economic rise of Asia, will, in a few decades time, result in a redefinition of the global North and global South, narrowing the definition of the global South to merely Africa and the Greater Middle East, and expanding the definition of the global North to everyone else.3

A major story in demographics at present is the accelerating decline of China. The 2018 UN forecast still predicted that China’s population would continue to grow until the mid-2030s. The 2022 revision, however, admitted that China‘s population would start to decline as early as 2023 and that India would surpass China the same year. However, developments during the last two years suggest that even the 2022 UN forecast massively overestimated China’s fertility, despite already being a major revision compared to the 2018 report. While the UN revision of 2022, using 2021 data as the most recent available, predicted 10.66 million births in China in 2023, down from 10.88 million in 2021. In reality, however, the Chinese birth rate in 2023 ended up being merely 9.02 million.4 The 2022 UN forecast did not expect China’s birth rate to plunge this low before 2050. Regarding total population numbers, China reports that its population fell to 1,410 million by 2023,5 in contrast to the UN forecast of 2022, which predicted that it would stand at 1,426 million by that year: a difference of 16 million people. However, it is not primarily the difference in the size of the total population, but the much more dramatic plunge of birth rates which, if continued, will inevitably result in a gradually widening gap between the 2022 UN forecast and reality, resulting in a significantly sharper decline of China’s population than that predicted by the UN.

Scholar Yi Fuxian goes even further. Based on discrepancies between official Chinese figures for certain age groups currently in their teenage years and stated birth rates in the years when they were born, as well as discrepancies between the stated number of newborns and the quantity of compulsory BCG vaccines given to newborns, as well as a police leak from Shanghai, he arrived at the conclusion that China started to falsify the published birth data from the early 2000s on, creating an ever-widening gap by the early 2020s. Based on these calculations, Yi Fuxian concluded that in contrast to the UN figures of around 1.4 billion, the population of China is only around 1.25 billion today, and by 2050, rather than declining to approximately 1.3 billion, as forecasted by the UN, it will decline to as few as 1 billion.6

While the conclusions of Yi Fuxian may or may not be correct, the rapid drop in China’s birth rate in the last two years suggests that China’s real figures will at least be closer to his figures than to the 2022 UN forecast. The expected 2024 UN revision will likely offer interesting conclusions on the matter. True, a moderately slow population decline may be manageable in economic terms, and had the 2022 UN forecast been correct with its predictions of a moderate and gradual decline, China could have been expected to manage this reasonably well. But the freefall in births that has come to light since 2022 makes it harder and harder to imagine China being able to avoid a major and long-lasting slowdown or even stagnation, and it will likely have to give up its dreams of becoming the strongest superpower on the planet, while if the estimates of Yi Fuxian turn out to be correct, the situation will be even more severe.

When Will Each Country Peak?

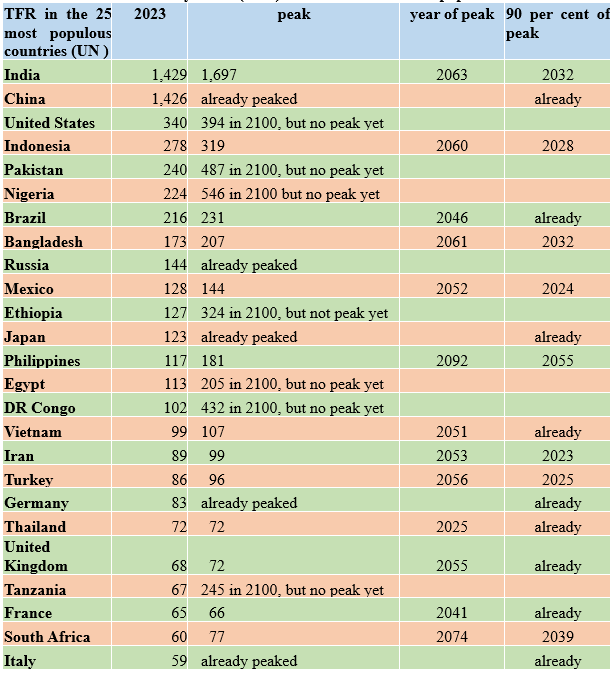

A major issue in terms of the demographic shift is when the population of each major will be slow and limited in scale, akin to that of the West at the end of the twentieth century. As shown in Table 1, among the most populous countries, while Europe, East Asia, and Russia are already declining, according to the 2022 UN forecast, countries that will reach this near-stagnation point within the next ten years include India in 2032, Indonesia in 2028, Bangladesh in 2032, power will peak. Besides the actual peak, however, perhaps an even more important point is when their population starts to stagnate. Of course, stagnation in a precise sense is almost non-existent, as there is always some degree of growth or decline, so as a definition, I selected the point at which the population of a certain country reaches 90 per cent of its own predicted peak. After that point, while there still is some growth, Mexico in 2024, and Türkiye in 2025. Iran, meanwhile, reached it in 2023, and Brazil, Thailand, and Vietnam passed it years ago.7

‘World Population Prospects – The 2022 Revision’, https://population.un.org/wpp/

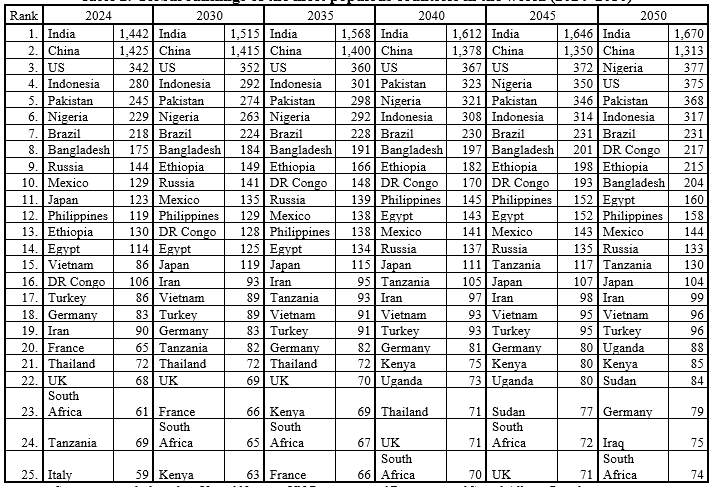

Shifts in Global Rankings

From a geopolitical point of view, changes in rankings of the most populous countries are also an important issue. Here, as shown in Table 2, I have selected the world’s twenty-five most populous countries. The relative decline of Europe, East Asia, and North America is also apparent here, with Indonesia, Nigeria, and Pakistan gradually catching up to the US. They are likely to become members of the 300 million club by the late 2030s, with Nigeria even predicted to surpass it as the third most populous country on the planet by 2050, together with Pakistan in 2053, making the US only fifth by population at that point, after India, China, Nigeria, and Pakistan.

The decline of Russia is also apparent. At the time of its dissolution in 1991, the Soviet Union was the third most populous country on the planet. The Soviet Union’s dissolution meant that Russia only inherited roughly half of its population, immediately putting it in sixth place in the global rankings, behind the United States, Indonesia, and Brazil. Since then, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Bangladesh have also surpassed it, leaving it ninth today. Ethiopia is scheduled to surpass it by 2028, the Democratic Republic of the Congo by 2034, Mexico and the Philippines by 2036, and Egypt by 2038, leaving it at fourteenth place in the global rankings by that year. This will most likely greatly hamper Russia’s position as a great power, and in the long run will render its aspirations to attain a position in the same league as China and the United States impossible. In all probability, it will have to settle for the role of second-tier great power, or merely a middle power.

The decline of Japan is also apparent, with Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Mexico, Nigeria, and Pakistan all having surpassed it since 1991. It is on course to be surpassed by the Philippines in 2026, and by both the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Egypt in 2028. As for how this impacts its global position, Japan will probably be able to counterbalance this trend for a time through the planned doubling of its military spending, which means that its military capabilities relative to the world will not suffer a setback as long as its share of the global GDP does not drop to half of what it is today.

Ethiopia and DR Congo, on the other hand, are likely to be among the top ten in terms of population within the next ten years.8 However, as we will discuss later, certain factors will probably prevent them for a considerable while from achieving positions of geopolitical power akin to that previously enjoyed by the two notable dropouts from the top ten, Japan and Russia.

‘World Population Prospects – The 2022 Revision’, https://population.un.org/wpp/

Shifts Between Regions

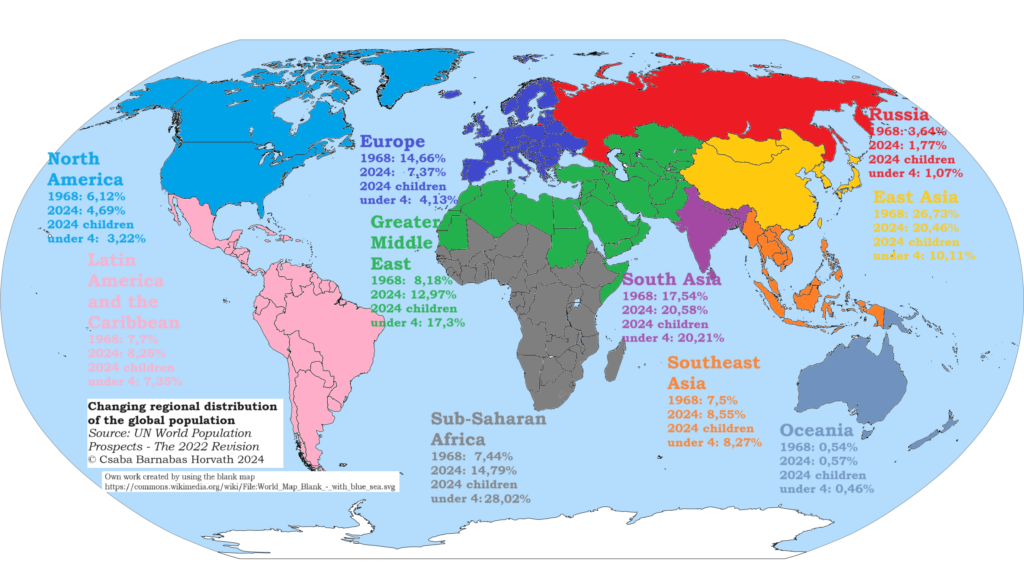

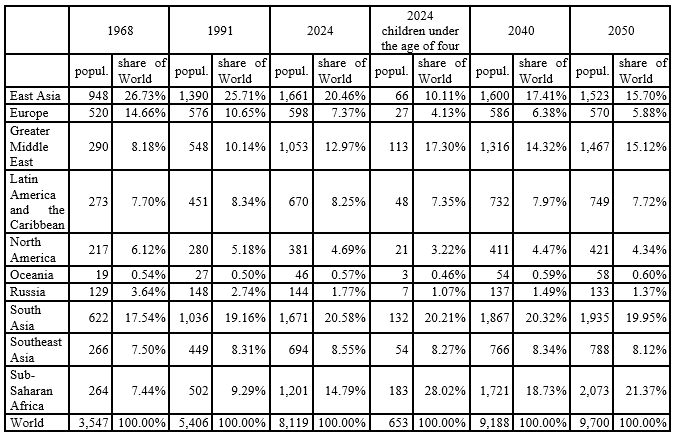

Alongside individual countries, it is also worth taking a look at the sum of the world’s major regions. Here, instead of the UN regions, I have grouped the countries of the Greater Middle East as one region, as they share several cultural, economic, and demographic characteristics (see Map 2). Of course, in this case, South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa refer to these regions minus those countries grouped into the Greater Middle East. I also treated Russia as separate from Europe due to its size, and this of course means, that Europe means Europe minus Russia.

Instead of absolute population, it seems more interesting to view the major regions in terms of their share of the population of the entire planet, since in geopolitical terms their relative position compared to the rest of the planet tells us more than the absolute numbers of their populations. In Table 3, I chose to compare these proportions in terms of certain milestone years: 1968, which can arguably be seen as the start of the postmodern era; 1991, the year that saw the dissolution of both the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union, and thus the end of the Cold War, therefore in a sense marking the start of the current historical era; and 2024, the current year. Years 2040 and 2050 represent future estimates.

Besides the total population for given years, I also add the proportion in each region of children from zero to four years of age this year, in 2024. The reason why it is important to know the relative proportions of this youngest living age group in each region is that this is not a forecast of the distant future, but already existing demographics. To put it simply, it is reasonable to assume that as this age group grows up, the global share of each region will shift to mirror the regional proportions within this age group. To be more specific, the shift in the proportion of different macro-regions in the global population is very likely not to stop before it reaches the proportions present among this age group, for the following reasons.

Even if average fertility rates subsequently equalized across all regions, by the time this age group reaches adulthood and has their children, this means the global share of regions would stabilize only when it reaches the proportions among this age group, which will already be a major shift from the world we know today. If fertility remains higher in regions where it is higher today (such as the Greater Middle East or Sub-Saharan Africa) when this age group has their children, this will result in an even more pronounced shift. The only plausible way for the actual shift to be less extreme than the proportions within this age group suggest is if fertility rates in the upcoming decade or two fall sharply in regions that have high fertility today, such as the Greater Middle East or sub-Saharan Africa, while remaining steady in regions where they are already low today, such as Europe and East Asia. In that case, by the time this cohort has its children, shares in the cohorts coming after them would be less extreme.

The demographic rise of the Greater Middle East, combined with the simultaneous demographic decline of East Asia, Europe, and Russia, will completely change the demographic and therefore presumably the security architecture of Eurasia. As we can see from the 1968 data, until the late twentieth century, the Greater Middle East represented a demographic void surrounded by the major demographic hubs of East Asia, Europe, Russia, and South Asia. However, when those in the zero-to-four-year-old cohort as of 2024 grow up, they will become the demographic centre of gravity of Eurasia, surrounded by a rapidly depopulating China, Europe, and Russia, with India being its only major Eurasian neighbour with demographics even remotely as healthy as its own. This means that by mid-century, demographic pressure from mainly Muslim immigration will probably become a common issue for China, Europe, India, and Russia at the same time. If this is accompanied by any kind of meaningful political unity in the Islamic world, then instead of the containment of China and Russia, or frustration with Western dominance, by mid-century, a coalition between China, India, the West, and Russia to contain Islam may become the major geopolitical issue of the day.

‘The power vacuum caused by the simultaneous demographic decline of the West, China, and Russia will probably make room for…rising middle powers’

The greatest growth, however, is obviously occurring in sub-Saharan Africa. Should the global share of the major regions of the world end up mirroring their current share among children aged four and under, the share of sub-Saharan Africa will become the largest, and the 2022 UN forecast likewise predicts this outcome by mid-century. Of course, the geopolitical impact of this trend remains to be seen. sub-Saharan Africa is even more fragmented politically than the Greater Middle East, and even more underdeveloped. While Islam may potentially become a unifying force for the Greater Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa is divided between Christian and Muslim-majority regions. The three most populous countries of sub-Saharan Africa affected by this population boom are the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, and Nigeria. All three, however, have certain geopolitical characteristics that greatly hamper them in converting their population growth into geopolitical power.

Ethiopia is landlocked, and in fact is the most populous landlocked country on the planet. Being landlocked is a major handicap for any country that aspires to become a major power, as it has no control whatsoever over the security of the shipping lanes vital for its economy, nor any ability to project military power beyond its immediate neighbours, and even its access to global markets is controlled by others. Of the three, however, at present only Ethiopia seems to show the kind of dynamic economic growth that characterized the rise of Asia, and without which no sub-Saharan African country can become a major power.9 Nigeria, meanwhile, not only possesses a reasonably long coastline fronting open ocean, but so far also seems to have done the best job in geopolitical terms, having spearheaded the formation of the West African regional bloc, ECOWAS, and becoming its de facto dominant power. However, the departure from ECOWAS of the three Sahel countries, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, which have formed their own bloc, represents a major challenge for Nigeria. DR Congo, having been tied down by decades of civil wars, has not yet even achieved the unity necessary to begin aspiring to become a major power, and even if it reaches that point, its extremely short coastline will prove a major geopolitical obstacle. All three are ethnically fragmented, and to make the issue even more difficult, Ethiopia and Nigeria are also split in half on religious lines, with roughly half of their populations being Christian, the other half Muslim, greatly increasing the risk of communitarian civil war in the future.

Where sub-Saharan Africa’s growth will almost certainly have a major impact is in terms of migration. If the global demographic share of sub-Saharan Africa ends up mirroring its share among the youngest cohort today, that would mean a doubling of its population compared to today. As migration out of sub-Saharan Africa is already a major issue, it would obviously turn into a far more significant issue if sub-Saharan Africa’s global demographic share were to double. Should the global proportions of the major regions end up mirroring their proportions in the youngest cohort today, and if sub-Saharan Africans move to Europe at the same rate as Romania’s population has moved to Western Europe since its EU accession, that would be enough to make them a majority in Europe.

In general, how the demographic rise of Africa and the Islamic World will impact global geopolitics is an equation with multiple unknowns. First, will any kind of meaningful supranational unity emerge in either Africa or the Greater Middle East? Both regions are politically fragmented, and even their most populous states, such as DR Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Türkiye, and South Africa are not strong enough to leverage this demographic rise to attain great power status of the sort enjoyed by China, India, or the United States. Therefore, to channel this demographic rise into the formation of global power, some kind of supranational entity would need to be created in either Africa or in the Greater Middle East. If, however, these regions remain politically fragmented, then no global power will rise in these regions despite their demographic rise.

The second question is whether Africa or the Greater Middle East will be able to replicate the rapid economic rise and modernization of China, India, and Southeast Asia. If they can, then combined with their demographic rise, this could lead to the rise of multiple major powers in these regions. If, however, apart from a handful of successful states dispersed across these regions, their economies remain underdeveloped, then their wealthier neighbours, China, Europe, India, and Russia will still probably be able to counterbalance their demographic rise with their technological edge.

The third question is whether any unifying political ideology or identity emerges in these regions, and if so, what kind. An important supplementary question here is, if any kind of unifying identity or ideology does emerge, then where will the geographical fault line between insiders and outsiders lie, and what kinds of tension will emerge along ideological or identity lines? For instance, should a unifying identity or ideology based on either religion or race rise, would that mark a major change in relations between North Africa and West Africa? Should a unifying identity based on Islam arise and become dominant, would this unite the Muslims of West Africa with the Muslims of North Africa and place the dividing line between Muslim majority and Christian majority areas within West Africa itself, thus essentially splitting Nigeria in half? If on the other hand, race were somehow to become a dominant factor, that would set the dividing line between West Africa and North Africa. In one of these scenarios, half of West Africa unites with North Africa but is separated from the other half of West Africa, while in the other, West Africa and North Africa become opponents. As West Africa is the most populous region of sub-Saharan Africa, this on its own could be a game-changing factor. Meanwhile, if the current bitter rivalry between Shia and Sunni, embodied in the Iranian–Saudi Arabian cold war, endures, any kind of unification of the Greater Middle East on a religious basis will be impossible. Of course, it is also very possible that no powerful unifying ideology or political identity will emerge in these regions, and that they will remain in the fragmented state that characterizes them now.

The major power that seems to have benefited most from demographics is India. While its fertility rate plunged below 2.1 at the start of the 2020s, and thus its growth is likely to stop early enough to prevent an overpopulation-driven ecological collapse, this will happen late enough to give it an edge over the other major global powers. With 17 per cent of all children aged four and under estimated to be living in India as of 2024, this means that if proportions of the total population come to mirror the proportions among children aged four and under today, then within a generation, India will not only have a population twice that of China, but will have a larger population than China, Japan, Russia, and all of Europe combined. Combined with its massive economic growth, this could make India the strongest power in Eurasia by mid-century.

How a Possible Civil War in Nigeria Could Unleash a Doomsday Scenario

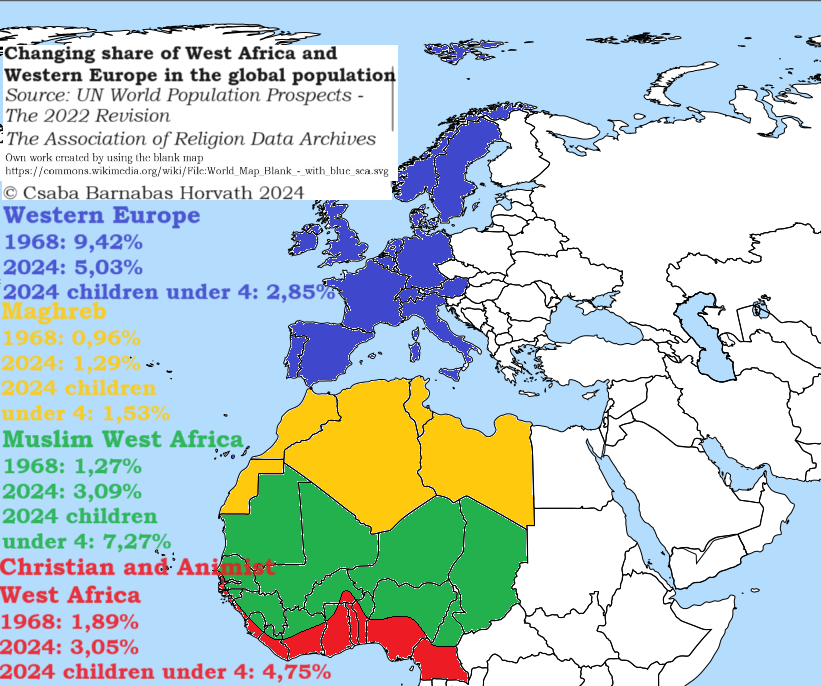

The questions concerning the dynamics of Africa and the Greater Middle East, as well as the sectarian fracture within Africa’s most populous country, Nigeria, lead us to address perhaps the most extreme case of the demographic shift currently underway: the Western Europe–West Africa axis, and within it, a worst-case scenario that could unfold if a sectarian civil war ever occurs in Nigeria, and ends up splitting the country in half.

Western Europe and Western Africa represent the closest geographical proximity between a major region with imploding demographics and a major region with exploding demographics, and this extremely sharp contrast will in all likelihood result in a stronger impact on interregional geopolitical dynamics than elsewhere, as well as a higher likelihood of issues regarding migration intensifying. The contrast for instance, may be as large or even larger between West Africa and East Asia, but they are much more geographically distant, with vast regions of intermediate demographic character between them, so the contrast will probably have much less direct impact.

To define the regions, I include Cameroon, Chad, and Mauritania in West Africa, as they share some significant cultural and geographical characteristics with other West African nations, while I have defined Western Europe as all non-ex-Communist European countries except for Finland and Greece, as the latter two share some significant characteristics with the eastern half of the continent. Due to the significance of cultural factors for the worst-case scenario in question, I have calculated two major subregions of West Africa separately: The Muslim part, which covers mainly the Sahel, and the Animist and Christian part, which covers mainly the southern coastal regions. Coastal West Africa, which is mainly Christian today, and the Sahel, which is predominantly Muslim, differ greatly in terms of historical, cultural, geographical, climatic, ecological, and ethnocultural characteristics. And apart from Senegal and Guinea on the western tip, where the two regions were joined, they never formed a common unit before European colonization. Of course, the dividing line splits the most populous country of West Africa, Nigeria, in half, so as long as the unity of Nigeria is maintained, this division is not of such vital political significance. However, should anything happen to Nigeria, the entire region would likely split into two. The 2023 establishment of the Sahel Alliance by Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger already separated much of the Muslim Sahel from the Nigerian-dominated West African regional bloc, ECOWAS.10 However, given that twice as many Muslims live in Nigeria as in the three Sahel Alliance countries combined, so long as Nigeria stands united, the Sahel Alliance remains a marginal power compared to ECOWAS.

Changes here are truly dramatic. While in 1968, Western Europe accounted for 9.42 per cent of the entire world, and Muslim West Africa accounted for just 1.27 per cent, as of 2024, Western Europe accounts for just 5.03 per cent, and Muslim West Africa for 3.09 per cent, while among the cohort of children aged four and under in 2024, Western Europe accounts for only 2.85 per cent of the world, while Muslim West Africa accounts for 7.27 per cent, as can be seen on Map 3. This means that, in a generation’s time, should the proportions of major regions mirror those among the youngest cohort today, Muslim West Africa would have a population two and a half times higher than that of Western Europe, and close to that of China, which stands at 8.7 per cent.11

In terms of demographic trends and their consequences, the Sahel is a region that has all the ingredients for a perfect storm. It is not only the region with the fastest growing population on the planet, but also the poorest region, while it simultaneously faces a high risk of desertification. Therefore, if there is any major region on the planet where the combination of population growth and climate change can indeed lead to an ecological-driven humanitarian disaster, it is the Sahel.

This alone, however, is not the most extreme outcome. The combination of a demographic explosion and poverty is often a hotbed for extremism, civil war, and revolutions. As the Sahel has this combination, the risk of extremism rising in the region is likely to be elevated. Jihadist groups such as Boko Haram and Ansaru are already present in the region. We have already seen, with the takeover of parts of Iraq and Syria by ISIS, or Islamic State, how in a turbulent region a jihadi group can take over significant territory. ISIS could not take control of the Alawi and Christian majority areas of Syria, the Shia majority areas of Iraq, or the Kurdish-majority areas of the two countries. It did, however, take over most of the Sunni-Arab-majority areas of both countries. If such events could happen in Iraq and Syria, we cannot rule out the possibility of something similar occurring in the Sahel, should demographic growth, combined with poverty and unfavourable ecological circumstances, lead to turbulent times in the region. To make things worse, the Sahel does not share the Sunni–Shia divide that arguably played a significant role in preventing ISIS from spreading into the western half of Syria and the southern half of Iraq.

As long as Nigeria’s unity under a secular government remains intact, however, such extremist groups can be kept in bay. First, should any such group threaten to take over significant territory in the region, Nigeria would certainly intervene and crush any such attempt, to pre-emptively halt the rise of such a potential adversary. And in such a case, even if such a polity were to emerge, so long as Nigeria is intact, with the most densely populated part of Muslim West Africa located within its borders, such a jihadist polity could only take over relatively thinly populated countries, such as Chad, Mali, or Niger. Should a sectarian civil war ever occur in Nigeria, however, and split the country in half, the picture would become very different. If any jihadist group were ever to secure control over the entire Northern half of Nigeria, there would be no regional actor capable of eliminating or even stopping such a jihadist entity, and uniting much of the Sahel could raise it to the position of a major if not dominant regional power, while simultaneously causing an unprecedented humanitarian disaster.

Should an ISIS-like jihadist polity take over and unite much of the Sahel in such a way, the sheer size of the population in the region would make it impossible for outside powers to deal with it the way they eliminated ISIS from Syria and Iraq. There is a broad consensus in military studies that to keep a population under military occupation, a military force needs one soldier for every 50 inhabitants.12 Were an ISIS-like polity to unite under its control even half of the 400–500 million Muslims that West Africa will have by 2040–2050, any attempt by an outside power to occupy it would necessitate a force of 4–5 million soldiers. Neither the United States, Europe, Türkiye, or the Arab World could be expected to be able or willing to deploy an occupation force of such a size, so should such a polity emerge, nothing more can be expected from these actors than attempts to poke it with air strikes and perhaps a naval blockade. The Christian-majority regions of sub-Saharan Africa to the south would likely have the necessary manpower for such an intervention, but it is highly doubtful whether they would have the necessary political unity, financial resources, weaponry, logistics, or infrastructure. Therefore, should an ISIS-like jihadist polity unite much of the Sahel under its control, it could become a power that no actor would have the force to eliminate, meaning that it would become a major power in its own right, in the new multipolar world. While the general economic backwardness would most likely prevent such a Sahel Caliphate from developing the air or naval forces needed for military reach beyond its immediate region, its manpower alone would make it a formidable threat for its immediate neighbours. As the population of such a polity could easily be drafted into an army of jihadist warriors millions strong, even if it remained underequipped, its attacks could still pose a serious threat to either the relatively thinly populated Maghreb or to the Christian-majority coastal areas of West Africa, by employing simple human wave tactics.

To summarize, should a sectarian civil war ever occur in Nigeria and split the country in half, with jihadist groups taking control the northern half of the country, it would create not only an unprecedented humanitarian disaster, but also a jihadist polity which no country in the Sahel would have sufficient resources to stop. Consequently, if the region remains as fragile and unstable as it is today, such a jihadist polity could have the potential to take over much of it. Thus, in such a scenario, the rise of a Sahelian jihadi empire with a population as much as twice that of Western Europe is quite conceivable. A humanitarian disaster of the magnitude that such a turn of events could inflict would also likely cause an unprecedented refugee crisis in the Maghreb and the Mediterranean, and such a Sahel Caliphate could also become a major expansive power in the region. As such, the stability and unity of Nigeria seems to be an issue of the utmost importance for not only West Africa, but also for the Maghreb and Western Europe as well.

Conclusion

The main conclusion of this overview may be that the demographic shift also suggests a move towards an increasingly multipolar world order. Not bipolar, but multipolar. While the West’s demographic weight is rapidly declining, so is that of its main opponent, China, and to such an extent that its aspirations to take over the role of global hegemon from the United States no longer seem feasible, and its economy may even slide into stagnation. Russia and Japan seem destined for a similar fate as that of the West and China, characterized by demographic decline, which will in all probability affect their role as regional powers as well.

The demographic position of India, which within a generation could have a population larger than China, Europe, Japan, and Russia combined, is so much stronger than those of China or the United States that combined with its robust economic growth, by mid-century it may be able to emerge alongside them as a third major power. However, even India’s demographic growth is slowing down, with its total fertility rate having already dropped below 2.1, and the real demographic explosion is going on in sub-Saharan Africa and the Greater Middle East. Due to the highly fragmented nature and relative economic backwardness of these two major regions, their economic rise is unlikely to result in the rise of great powers in the same league as the United States, China, and India, unless some supranational entity emerges to unite a significant part of these regions. Instead, a number of middle powers seem likely to emerge in these demographically growing regions. The power vacuum caused by the simultaneous demographic decline of the West, China, and Russia will probably make room for these rising middle powers, ultimately further accentuating the multipolar nature of the new global order.

NOTES

1 ‘The Greater Middle East Initiative’, Al Jazeera (20 May 2004), www.aljazeera.com/news/2004/5/20/the-greater-middle-east-initiative.

2 United Nations, ‘UN Population Division Data Portal’, UN.org, https://population.un.org/dataportal/home.

3 United Nations, ‘UN Population Division Data Portal’, UN.org, https://population.un.org/dataportal/home.

4 ‘China’s Population Falls by 2.08 Million to 1.4097 Billion in 2023 as Births Tumble, Adding to Demographic Concerns’, South China Morning Post (17 January 2024), www.scmp.com/economy/economic-indicators/article/3248695/chinas-population-falls-208-million-14097-billion-2023-births-tumble-adding-demographic-concerns.

5 ‘China’s Population Falls by 2.08 Million …’.

6 Yi Fuxian, ‘Leaked Data Show China’s Population Is Shrinking Fast’, Project Syndicate (27 July 2022), www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/chinese-population-smaller-than-stated-and-shrinking-fast-by-yi-fuxian-2022-07.

7 United Nations, ‘UN Population Division Data Portal’, UN.org, https://population.un.org/dataportal/home.

8 United Nations, ‘UN Population Division Data Portal’.

9 International Monetary Fund, ‘World Economic Outlook Database’, IMF.org, www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/October/.

10 ‘Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso Establish Sahel Security Allliance’, Al Jazeera (16 Spetember 2023), www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/9/16/mali-niger-and-burkina-faso-establish-sahel-security-alliance.

11 ‘Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa’, Pew Research Center (15 April 2010), www.pewresearch.org/religion/2010/04/15/executive-summary-islam-and-christianity-in-sub- saharan-africa/; and The Association of Religion Data Archives, www.thearda.com/world-religion/national-profiles?u=20r, accessed 10 April 2024.

12 ‘A Proven Formula for How Many Troops We Need’, The Washington Post (8 May 2004), www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2004/05/09/a-proven-formula-for-how-many-troops-we-need/5c6dbfc9-33f8-4648-bd07-40d244a1daa4/.

Related articles: