In a globalized economy shaped by social media and artificial intelligence, the forces that influence our personal identities have become increasingly transnational. Many believe that these forces now play a more significant role in shaping values, aspirations, and social behaviour than national identity does. The international system constructed by the United States after World War II fostered global trade, industrialization, and large-scale urbanization. Between 1950 and 2020, the global urban population increased from approximately 30 per cent to 56.2 per cent of the total population, with projections indicating a rise to nearly 70 per cent by 2050. Simultaneously, global life expectancy at birth rose from around 46 years in 1950 to approximately 72.8 years in 2019.

Sociologists and market researchers have coined a variety of generational labels such as Baby Boomers, Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z to describe the cultural and economic distinctions among people born at different stages of globalization. These labels attempt to make sense of how shared historical conditions shape attitudes and expectations. Ipsos recently published the Ipsos Generation Report 2024, a comprehensive study of generational attitudes in 29 countries, challenging many of the myths promoted by pop sociology. Their research sheds light on both the global commonalities and regional divergences that define each cohort. Urban life transformed the logic of reproduction. Unlike in rural economies—where children often served as free labour and a form of old-age security—urban environments redefined children as costly investments. This structural shift gradually led to declining fertility rates; a trend further accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

‘We are entering a historical era never seen before: a world in which population naturally contracts, and young people constitute a shrinking share of society’

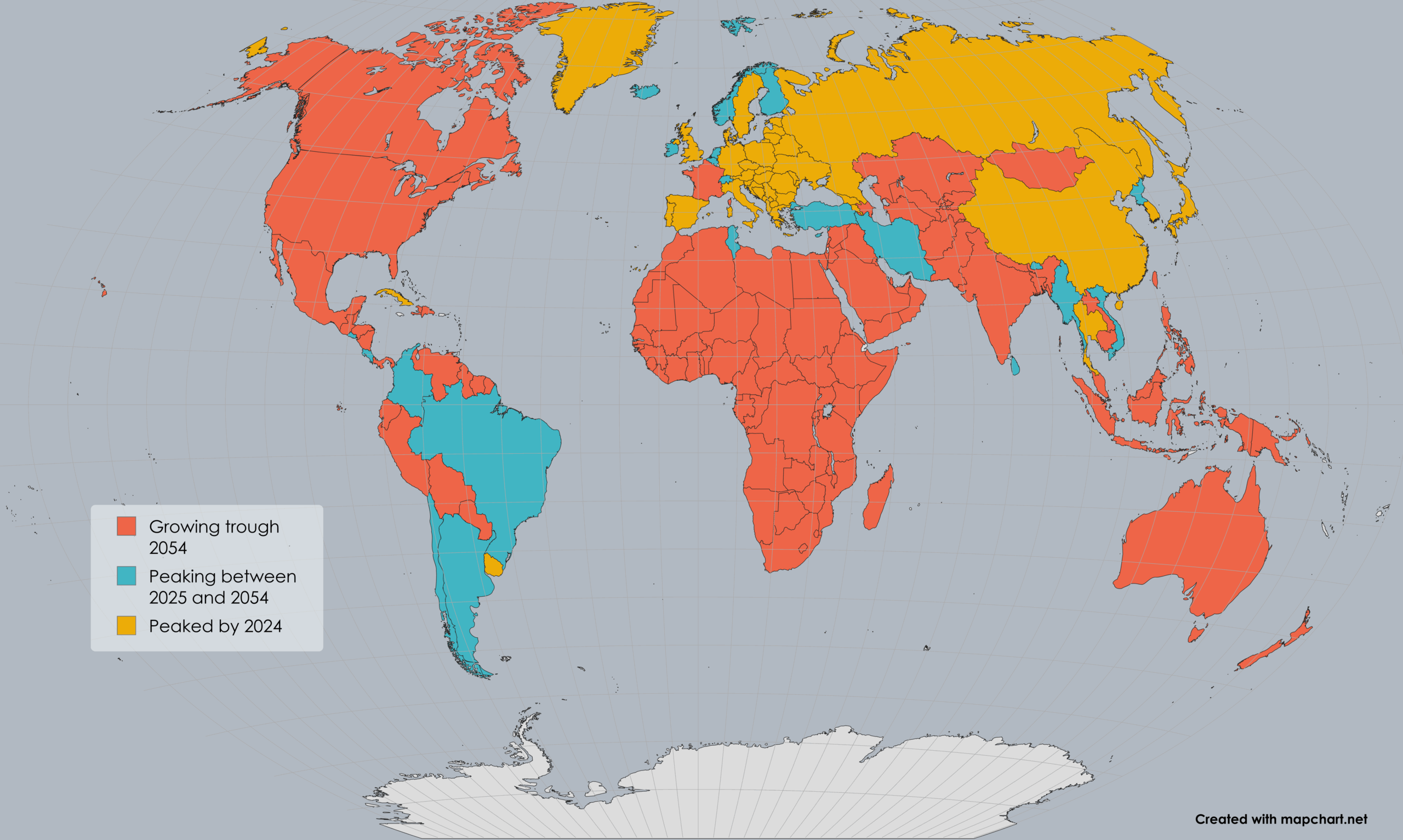

In the United States the ‘Baby Boomers’ (people aged 59–79) represent 27 per cent of the population, but control 70 per cent of the assets. In China, approximately 25 per cent of young people are unemployed. In Europe, many working-age individuals are watching their savings erode amidst persistent economic stagnation, while older cohorts continue to benefit from the legacy of post-war welfare systems. In addition, today, except for a few Central Asian, African countries, and India, nearly every major and mid-sized country has a fertility rate below the replacement threshold. This rapid aging of global populations is producing new social tensions. As policymakers, academics, and business leaders increasingly confront the challenges of demographic decline, it becomes essential to understand the cultural divides and shared concerns that shape generational identities. We are entering a historical era never seen before: a world in which population naturally contracts, and young people constitute a shrinking share of society.

Problems with Generational Definitions

The practice of defining age cohorts with labels like Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z has become commonplace, but these definitions can also be misleading. One issue is that such labels are not universally applicable or understood. As the Ipsos Generations Report (2024) notes, the term Baby Boomers might make sense in the Anglosphere, but in countries like Brazil, Nigeria or India there was no such boom at this time, and people just don’t know what this term means. In fact, generational labels in general do not translate well globally. Ipsos found that on average across 29 countries, under half have heard of Generation Z, Millennials or Generation X. Even in the United States, where these generational labels originated, awareness is mixed: around 62 percent of Americans can identify their generational category, but only 48 percent of Gen Z are able to do so.

Generational boundaries are further complicated by the fact that demographic transitions unfolded differently across the globe. While the US experienced its peak birth rate in 1957, Brazil’s came earlier in 1950, India’s in 1964, and Nigeria’s as late as 1978. As a result, terms like Baby Boomer do not correspond to the same demographic phenomena across countries—or may not apply at all. In South Africa, people born after apartheid are called the ‘Born Frees’, while in Germany, those who entered adulthood after reunification are sometimes referred to as ‘Generation 1989’. In Germany, the ‘Generation 68’ label reflects the student protest movement more than birth cohort. Norway has its own set of labels such as the ‘Dessertgenerasjonen’ (those who grew up with the welfare state) and the ‘Ironigenerasjonen’ (born in the 1970s with a distinct cultural mindset). These local labels reflect specific historical and cultural turning points rather than demographic bulges. Furthermore, the timing of modernization, education expansion, and access to technology differ across societies, making shared generational traits elusive. For instance, Millennials in the US might associate their coming of age with the rise of social media, while in rural India or Sub-Saharan Africa, that association might only apply to Gen Z.

Behavioural and Cultural Distinctions Across Generations

Nonetheless generations do exhibit distinct behavioural and cultural patterns, shaped by the eras in which they grew up. The Ipsos report identifies several ways today’s younger generation (Gen Z) differs from their predecessors. One striking finding is that Generation Z displays higher levels of stress and loneliness. Across many countries, people born since the mid-1990s report markedly more stress about their lives and often feel lonely, a trend not as pronounced in older age groups. This could be partly due to context—Gen Z’s adolescence and early adulthood coincided with financial crises, a global pandemic and incessant social media pressures. Indeed, this generation has been bombarded with the same news and online content worldwide, possibly amplifying shared anxieties. The COVID-19 pandemic in particular hit Gen Z at a formative time, disrupting education and social life everywhere at once. But there are similarities too. 56 per cent of mature adults say they feel good both physically and mentally compared to 56 per cent Millenials.

Another difference is in social connectivity and relationship patterns. Gen Z are ‘more likely to spend time interacting with friends online than offline, and more likely to form relationships online than any other generation.’ This doesn’t mean they reject in-person friendship—rather, digital socializing is an added dimension that older generations didn’t have in their youth. Many Gen Zers maintain hybrid social lives, but the balance skews more toward online communication.

‘Younger cohorts were more likely to reject traditional gender roles than older ones, even where such roles remain culturally dominant’

Values and attitudes are another area of generational distinction. Younger generations tend to be more progressive on social issues than their elders. For example, when asked about gender roles or LGBTQ+ rights, Gen Z and Millennials are often more liberal. The report suggests that some value differences can indeed be attributed to cohort change, not just age. When looking at attitudes toward traditional gender roles, ‘differences between generations can be just as great in countries where [a particular] attitude is in the minority (e.g. Thailand) vs countries where it is far more widely shared (e.g. Great Britain).’ In both a relatively conservative society and a liberal one, young people diverge from their elders in similar ways (though at different baseline levels of conservatism). Still, culture mediates these effects. For instance, ‘US Gen Zers are almost twice as likely to disagree that the role of women in society is to be good mothers and wives than Thai Gen Zers.’ Over 60 per cent of Gen Z respondents in Great Britain disagreed with the idea that a woman’s main role is domestic, while fewer than 30 per cent did so in Thailand. Across all surveyed countries, younger cohorts were more likely to reject traditional gender roles than older ones, even where such roles remain culturally dominant. This suggests a consistent generational shift in values, moderated—but not cancelled—by national context.

Recent data suggests that declining fertility is driven more by personal and structural barriers than by ideological shifts. Among respondents in 29 countries, 24 per cent cited physiological reasons, 18 per cent pointed to financial pressures, and another 18 per cent noted situational factors as key reasons for not having children.Only 11 per cent blamed the ‘state of the world’, and just 7 per cent expressed a lack of desire to become parents. These findings contradict common cultural narratives that attribute falling birth rates to pessimism or anti-natalist sentiment among the young. Instead, the decision not to have children appears grounded in constraints rather than rejection—a generational behaviour shaped by tangible realities, not just values.

Depopulation: Challenges and Opportunities

The Ipsos report highlights that the ‘prospect of global population decline from the middle of this century now looks irreversible.’ Already, over 30 countries have shrinking populations, and even globally, fertility rates are falling faster than anticipated. This depopulation trend presents profound challenges. For one, economies have long been built on the assumption of constant growth fuelled with rising populations. Now, policymakers must confront the opposite: ageing, dwindling populations mean fewer working-age people to sustain pension systems and slower expansion of markets. We are already seeing debates around raising retirement ages and labour shortages in countries like Japan, Italy, and parts of Eastern Europe where the population is skewing older. In essence, the demographic balance is tilting, and with it comes economic strain and the need for policy innovation.

However, depopulation is not solely a story of decline—it also creates new opportunities and forces us to adapt in positive ways. As the number of children born drops and life expectancy rises, the centre of gravity shifts to older generations. Businesses and governments can seize this moment to better serve the often-overlooked senior population: this large segment of the population with significant wealth and specific needs. Forward-looking companies are developing products and services for the ‘silver economy’—from healthcare and assisted living technologies to travel packages designed for retirees. Older individuals today are more active and engaged than in past generations, and many wish to continue contributing to society if given the chance. Policies that facilitate longer working lives (for those who can and wish to work) or that harness the volunteerism and experience of seniors can help mitigate some challenges of a smaller workforce. Moreover, a slower-growing or contracting population could reduce environmental pressures and force improvements in productivity and automation.

Related articles: