This article by Ákos Győrffy was originally published in the Hungarian Chronicle in 2021.

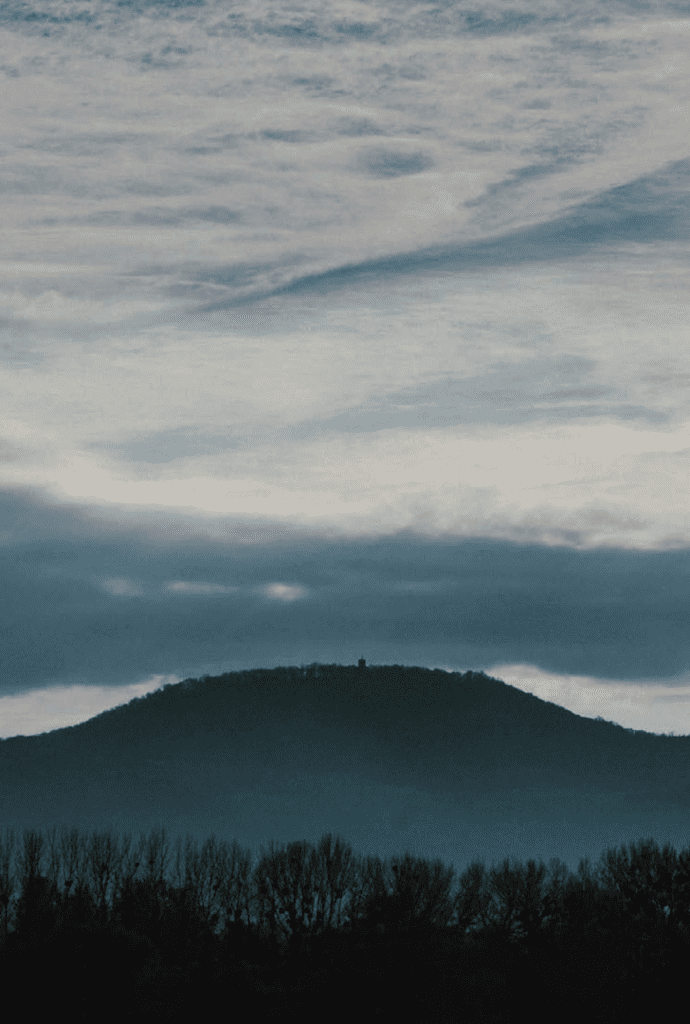

The loneliness and silence of the Danube Bend in the winter is difficult to describe, but pictures can convey, perhaps, the story of the river and the mountains—a story beyond words. In frost and chill I recall the beginning, one summer long ago, when my life was intertwined with the Danube Bend for good.

It was 1994, after I graduated from high school. I was not concerned with what should come next, I just knew that something completely different should start happening, something with a purpose, something that makes real sense. I could only rely on hazy hunches, vague intuition, mysterious messages from a world I knew almost nothing about, feeling only its call, which was stronger than anything.

A friendship about to start illuminated previously invisible paths leading to this exciting secret world where I had always wanted to go.

And a year came when sunrise caught us in front of a fish-and-chips booth on the riverbank almost every morning, leaning over a crumpled map to pick our trails. We pointed, fingers trembling with excitement, at peaks, valleys, and mountain shelters. Prédikálószék, Hegyes-tető, Csóványos-distance and difference in elevation were excluded from our calculations. The bicycles were propped against the trunk of an old poplar. We had a hundred forints, enough for a cheese sandwich, spritzer, and a pack of cigarettes. Our torn map was the imprint of a world full of enticing promises, ruins of cloisters, clouds reflected in ancient wells, gothic ceilings of beech forests, fragrant and sun-drenched oak groves, nameless streams springing up from thick cushions of moss, hazy or sharp vistas from high ground, stone crosses by the roadside, and strips of fog over the Danube. We were facing such a torrent of impressions and images we did not even dream of. It was as if the golden gate of childhood, believed to have been lost for good, opened again. The scenery was of a golden age, and we were intoxicated by it, almost forgetting our own names, completely losing our sense of time.

Bicycles were horses; we always patted the frame before setting out. There was nothing theatrical or intentional in this, it came naturally. We were discovering the meaning of space.

We suspected a secret in everything, a secret known by everyone, but never discussed by anyone.

It was not mentioned by our parents, it was not covered at school. But making music, wandering around in the woods, and poetry seemed to bring the secret closer. We spent many hours in village pubs talking, talking, and talking, sharing life confessions under the trees. We often repeated that an unbelievably hefty tome, the ‘Book of the Danube Bend’, must certainly exist in the next world, in which everything we say is recorded. The book will be thicker with each passing day, and the first thing we will do after we die is read it all, from the first page to the last.

I don’t have too many specific ‘standalone’ memories from this period. It is more like a radiating, living texture in my mind, assembled from shapes, smells, sounds, and colours, something that is hidden behind every thought, illuminating with its special light every moment of my life. It was an initiation, a series of definitive experiences, a ritual bath in the baptismal water of eternity. In the Danube Bend I found my intellectual and spiritual home, a fixed point, unaffected by time, like the North Star. The Danube between the Pilis and Börzsöny mountain ranges became the axis of my world. There are countless such axes, I’m sure everyone has their own, but for me, this immense river-bend is home country, it is where I feel at home in this increasingly alien world. There are higher mountains, bigger forests, and wider rivers. Here, in the Danube Bend, nothing is grandiose; it is a gentle landscape, on a human scale, without anything grim or scary. Perhaps it was no accident that our kings liked to stay here so much that they built castles, fortresses, and churches, and their memory is preserved in the names of meadows and springs. Perhaps they felt the same way I do: this is a truly special corner of our country, with energies that help us to live our lives, and to see more clearly what life is all about.

Related articles: