The ‘coffee house cult’ in Hungary started to take off in the 1800s. From that time onwards, they functioned as a community space, the main arena of cultural and political life, and a place where visitors could easily access all the information they needed and wanted. Romances started, poems were written, agreements were made, and revolutions were organized in these coffee houses. By the turn of the 20th century, Budapest had already 500 cafés, most of them located in the boulevards, Andrássy Avenue, and Rákóczi Avenue. Every political society and literary circle had its own haunt or even its own regular table.

Central Café

Central Café was one of the most important, and perhaps best known, intellectual centres of Hungarian literary life. It opened its doors at 9 Károlyi Street in 1887. For several decades it was the haunt of a very distinguished society, notably the writers of the Hungarian literary journals A Hét (The Week) and Nyugat (West). József Kiss moved his ‘Round Table’ here from the Korona Café on Váci Street, and established the editorial office of A Hét here, in the new headquarters. Not much later, younger writers who had left A Hét soon founded Nyugat here. During this period, the editors met every Tuesday as part of the ‘Nyugat tea party’, a compulsory gathering at the well-known corner table in the Central, where everyone knew who it belonged to, and on Wednesdays, poetesses held their meetings at the same place. The famous ‘Nyugat’ table was located in the corner, and it was not uncommon to find guests who came in just for the company. The café is still open today, under its original name and in its original location.

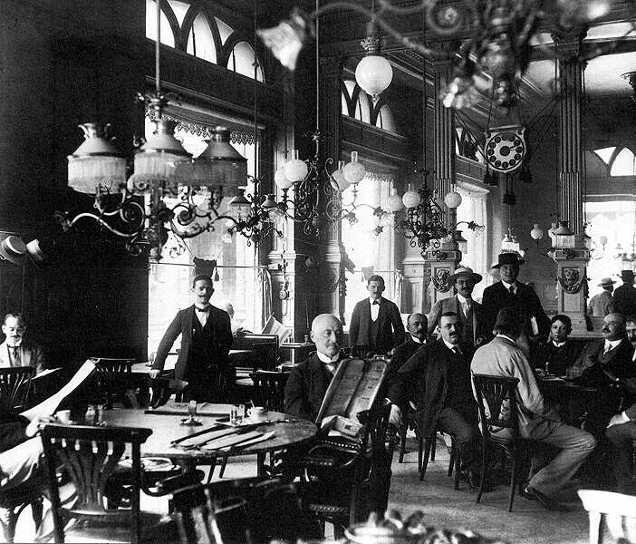

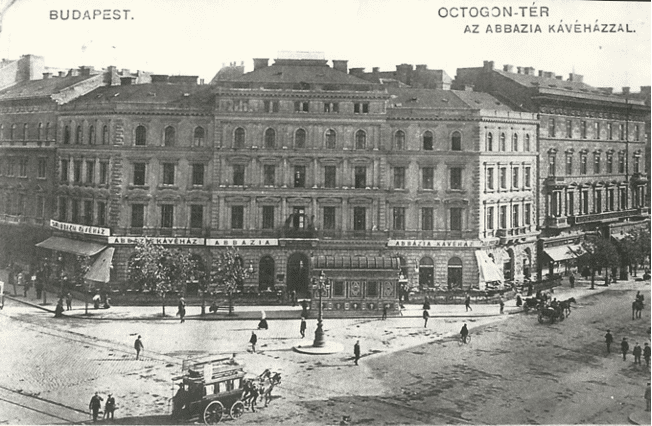

Abbazia Café

Abbazia was inaugurated in 1888 at the Oktogon. Its founder was Gyula Steuer, who revolutionized the ‘coffee business’ by keeping the café open around the clock, abolishing closing hours. For several decades, the modern Abbazia, with its gleaming wall mirrors, was considered the most beautiful and luxurious café in Budapest. Károly Eötvös, politician, lawyer, writer, and member of parliament, spent most of his days here. The publicist, also known as ‘the Voivode’, was one of the most prominent public figures of the time and was always surrounded by a large number of people, which contributed to Abbazia’s popularity and the establishment of a quality clientele. The audience gathered around the marble tables listened to Eötvös’ speeches and analyses as if in a trance.

Writers Ferenc Molnár, Sándor Bródy, and Jenő Heltai, as well as politician Vilmos Vázsonyi, who founded the Democratic Circle of Citizens here in 1894, also fancied sitting around the marble tables in Abbazia.

However, Abbazia’s regulars had moved away from their favourite haunt by the 1890s, and the reason for it was quite strange. The illustrations from the various newspapers and magazines distributed in the café were a favourite with the guests, who liked to cut them out and take them home. The newspaper scraps left behind understandably displeased the café managers, who wrote on each illustration of the papers: ‘I stole this picture from the Abbazia’. This caused such controversy and resentment among the guests that they rather moved their headquarters to the nearby Japan Café.

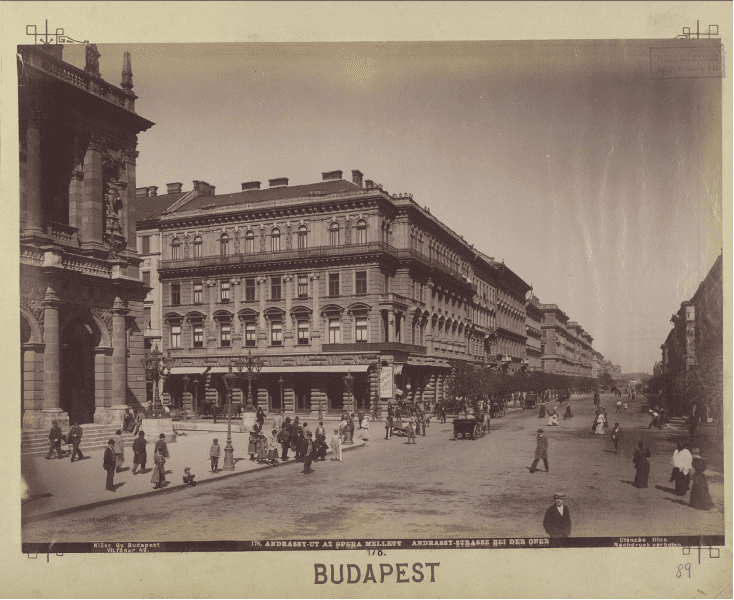

Japan Café

Japan opened in the 1890s at 45 Andrássy Avenue—today, it is the site of the Writers’ Shop. The café not only served coffee, but the cuisine was also excellent. Because of its location, it was a great place to grab a quick bite before or after a theatre performance. The artist’s table by the window overlooking Andrássy Avenue was a favourite spot of Ödön Lechner, who dreamt and sketched the floor plans of several of his famous buildings here while discussing with renowned painters Pál Szinyei Merse and Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka.

The café’s heyday was under the leadership of Menyhért Kraszner. Kraszner did his utmost to please his guests and to keep Japan a deservedly popular café. He provided credit to the regulars, gave discounts, and of course had a kind word or two for everyone. Famous poet Attila József also used to come here at the time, and when he was not working on his poetry, he often liked to invite other guests to a game of chess. Other frequent guests in Japan were writers Dezső Kosztolányi and Frigyes Karinthy, as well as poets Zoltán Zelk and Ignotus.

Three Ravens Coffee House

Famous poet Endre Ady spent most of his time at the Three Ravens, which opened in 1888, right next to the Opera House, on the corner of Andrássy Avenue and Hajós Street, and used it as a kind of workroom, as he practically spent more time here than at home. The coffee house itself was special because

it was furnished with ‘private’ booths separated by curtains, where visitors could find peace and quiet and create their own little private space.

At the Three Ravens, life really started to get going at 10pm: like many other coffee houses, there was no closing time in Three Ravens either, so many people spent the night in the booths or sitting around the tables. Most of Ady’s poems for Nyugat were written here, but writer Béla Révész, who liked to admire the Opera from the coffee house, also worked on the journal Népszava in the Three Ravens, although he did not really tolerate it when the aforementioned poet, who was a notorious womanizer, brought unexpected guests into his booth…

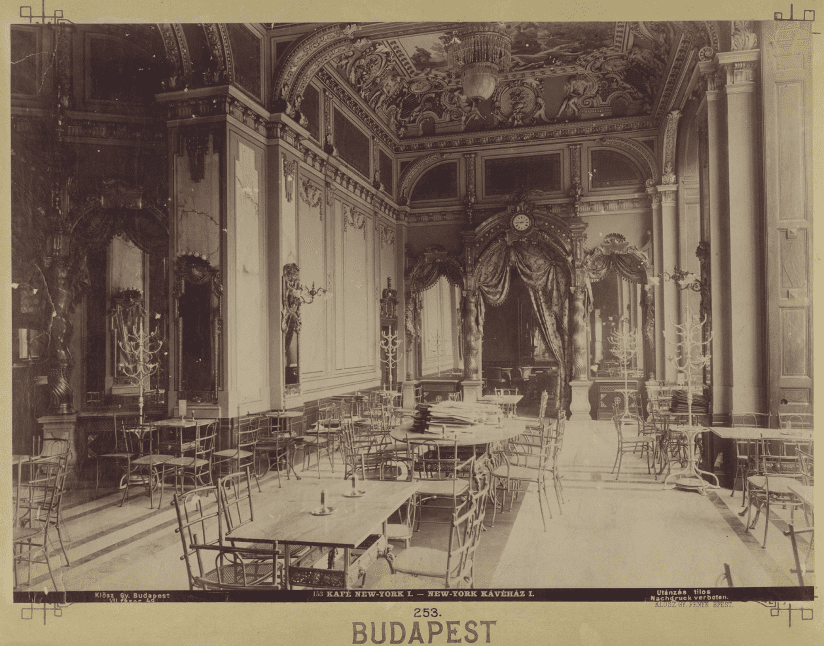

New York Café

In 1894, the New York Café on the Grand Boulevard solemnly welcomed its first guests. It was built on what was then a suburban boulevard back then. However, as urban planning progressed, imposing buildings like this became more and more common, and thus the downtown area expanded as well. Architect Alajos Hauszmann was commissioned by an American insurance company to design the edifice, as the city was developing rapidly at the turn of the century and there was no shortage of new investments either. With its gilded, twisted Baroque columns, fountains, and sculptural decorations, it is no wonder that it was known as the ‘most beautiful café in the world’. Soon, the usual assemblies at certain tables were formed here, too, seated in cliques over the several floors of the café.

The waiters tried to please the litterateurs: they served free drinks and oblong sheets of paper in addition to their orders.

The editors of Nyugat always sat in the gallery, led by Endre Ady, Jenő Heltai, and Ignotus, and only later reorganized at the Central Café. Besides that, several poems by Frigyes Karinthy, Dezső Kosztolányi, Gyula Krúdy, and Ferenc Molnár were also written here. Although the change of ownership after the First World War caused the literary scene to fade, it still continued to play an important role in Budapest’s coffee house life.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.