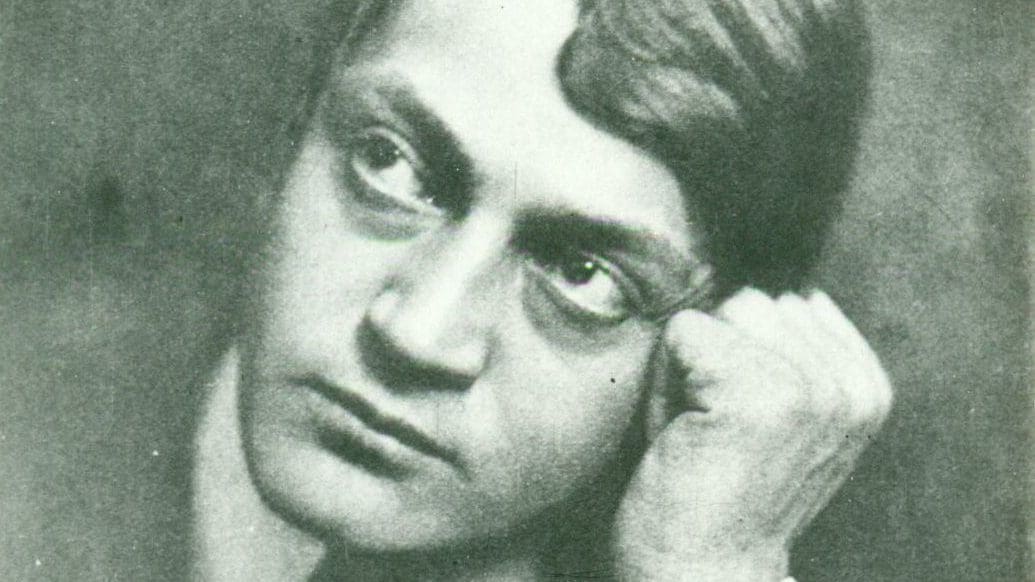

About one hundred years ago, a press debate raged between the liberal and the nationalist writers for dominance over Hungarian cultural life. The “counter-revolutionary” system was able to win over some already famous authors such as Aladár Schöpflin of the Nyugat – now theatre editor of the right-wing journal, Szózat – or Dezső Kosztolányi, who wrote antisemitic articles under a pseudonym. Yet there was someone, who could no longer speak for himself. Only his poems – often contradictory writings that could be interpreted in many different ways – testified to his views, which were quoted by his admirers, opponents, relatives and former friends for the sake of different political strains.

The left-wing radical Oszkár Jászi saw Endre Ady as a ‘genius’,[1] while former conservative Prime Minister István Tisza simply said that ‘Ady and the journal Nyugat are parasites on the tree of Hungarian culture’.[2]The classical liberal Jenő Rákosi wrote perhaps a more correct critique when he thought he discovered “decadence” in Ady’s poetry, which was ‘confused, sometimes to the point of meaninglessness’.[3] Also worth quoting is the opinion of the bourgeois liberal Károly Szász who considered Ady’s poems the ‘confused creations of a sickly exalted man’.[4]

Ady was indigestible for the extremely divided contemporary public opinion: his Transylvanian noble origins and freemasonry, his left-wing views aspiring to socialism, his poems calling for a “red revolution” and his self-flagellatory nationalism, his pious poems and his self-destructive way of life meant such a cavalcade, from which everyone was able to extract a version of Ady who justified his views.

The conservative Magyar Helikon correctly wrote in 1921 that ‘Ady’s poems are like his soldiers, beating each other to death’, since there are ‘valuable ones [and those] that are not even worth reading’.[5] However, some facts were not a matter of interpretation: Ady really lived a decadent life, he had occasional relationships with many lovers – and prostitutes – during which he contracted syphilis, and he also smoked and drank heavily. When fellow writer Gyula Krúdy tried to defend the poet in 1925, he didn’t even manage to give a better picture of Ady: as a grown man, he still ordered black coffee when the last pubs were closed, then with two bottles of wine in his coat pocket, reeking of onion, cigars, alcohol and cologne, he tried to climb the statues next to the steps of the National Museum. Finally, he ended up on the ground, his hair in a mess and drunk, Krúdy recalled.[6]

‘Ady’s poems are like his soldiers, beating each other to death’

Ady died young, during the Aster Revolution, as a complication of his venereal diseases; according to some, he even welcomed the left-wing takeover, declaring that ‘a hundred heavens could never have been more beautiful’. His younger brother, Lajos Ady, thought to refute this later.[7] But his writings seem to confirm the former story. Ady, who moved in radical-freemason and socialist circles, was truly a supporter of the revolutionary idea. In his poems, he prays for the coming of the “apocalyptic red day”, the realisation of the “red Sun”, and the rise of the “red Star”, which will wipe out the noble, reactionary Hungary. And in his voluminous publicism, he called himself the “professional singer of socialism” and also described what a “real liberal” is for him: a “socialist, a radical, a revolutionary”. But, as he explained in his article The Raised Red Flag, he did not really see himself as a liberal: ‘Classical liberalism has failed. Radicalism is needed’. Elsewhere, he added that the Hungarian citizenry should erect a statue to ‘Karl Marx and Ferdinand Lassalle.’ In one article he wrote that ‘I am not an economist, [but] I subscribe to Marx’, and in another piece he proposed the destruction of churches and synagogues and the construction of industrial plants in their place. In yet another one, he demanded the confiscation of church property. In the two thousand page collection of his articles, hundreds of times he calls for revolution, condemns “reaction” and refers to socialism.[8]

In spite of his clear and unmistakable message, the struggle over Ady’s memory began shortly after his death and was still in full swing in the early twenties. According to the opinion of the socialists – which was ironically best expressed by Dezső Szabó his book The Revolutionary Ady, published during the 1919 Soviet Republic – Ady was a promoter of the new, fairer red world. As he wrote, ‘Ady’s teaching[:] capitalism and free market competition are death for Hungarians unable to compete… There is only one refuge:… all Hungarians… throw themselves into socialism to prepare the… communist world order’.[9]

Meanwhile, the “counter-revolutionaries” wanted to see in Ady an ethnic Hungarian socialist corrupted by the Jews, a left-wing nationalist suffering from the “Jewish yoke”, a struggling Protestant. The latter opinion was voiced by the literary historian János Horváth’s pamphlet From Arany to Ady. He wrote in 1921 that ‘Ady threw himself into the maelstrom of Jewish influence’,‘whose true goals he did not recognize, or recognized too late, and which used him as a battering ram against his own people, and even against the interests of the Hungarian race’.[10] Traditional liberalism was responsible for Ady’s downfall, concluded Horváth.

The right-wing poet István Lendvai – one of whose biggest inspirations was Ady – enthusiastically welcomed Horváth’s book and wrote that every Hungarian university student should read it, because the work perfectly summarises how the old-fashioned liberal-conservative thought handed over to the Jew the Hungarian geniuses. While we should not forget that in 1944-45 Lendvai became an anti-Nazi resistor and martyr, his 1920 poem about Ady shows little of his good qualities. In Lendvai’s poem, Ady confesses his Jewish deviance before God in heaven, and then receives forgiveness: ‘I insulted my race, / I spat on my country, / (…) I became the persecutor of my poor race, / I condemned her to death in return for some shekels’.[11]

Horváth was not an awakening Hungarian, but Endre Zsilinszky – who did not use the name Bajcsy at the time – agreed with him in his condemnation of the conservative-liberal system of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As he wrote, ‘we are one with Ady in our great disgust’ for the old, ‘despised, hated’ Hungary, and we must reject the criticism of the conservative-liberals, since their rule was primarily responsible for Ady’s disfigurement: ‘They hate Ady because he was a swamp creature; we hate the swamp’.[12]

According to him, in order to see the value of Ady, we should despise the old system

According to him, in order to see the value of Ady, we should despise the old system, ‘also the deep Hungarian mistakes of the two generations before the great war, that bog of deep rot, on top of which the ugly, musky flora of alien-minded revolutions grew; we should also see the Hungary of lies, self-delusions, beautiful words, self-serving rhetoric, and poisonous thoughts draped in national colours; where the sick individual selfishness of a society falling apart and the well-organised foreign robbery of our wealth had its orgies. . . the sad Hungary of fruitlessly fallen flames and talents’.[13]

Zsilinszky fought a windmill battle if he thought that the old friends of Ady, Mihály Babits or Zsigmond Móricz loved the old Hungary; their leftist views were just as opposed to the conservative-liberal system of dualism as the nationalist anti-capitalism of the fajvédős. Móricz wrote in a belated epitaph addressed to Ady that ‘It’s terrible to think about it, / They falsify / all the meaning of your life’.[14] However, the nationalists aptly praised Ady’s anti-capitalism. Babits could only write in his old friend’s defence that ‘Ady was very far from being the poet of Bolshevism’ – which was not surprising, given that he died before the 1919 Kun regime -, but he also stated that ‘the embers still burn. The revolution can be stifled with blood and dirt: the poet of the revolution lives forever’.[15]

Ironically both the liberals and the nationalists wanted to protect Ady, primarily not from each other, but from the long-defeated conservative-liberal side; both rejected the conservative-liberal criticism of Ady by Tisza, Rákosi and Ferenc Herczeg as an attack from the past regime, the old masters of Hungary. The debate took place only around the superficial question of how “Jewish” Ady was.

While Lendvai believed that Ady was deceived by the “Hebrew swindle called communism”,[16] Babits argued that Ady saw the bigger picture, the liberation of the Hungarian race, and since Babits also denied that “Jewish character” as such existed (‘I consider it a superstition that the Jew is a mystical species different from everything else’[17]), so he closed the debate by saying that ‘it is not worth wasting a word on this nonsense’.[18]

The debate was, of course, completely barren from this point of view: it was Ady’s revolutionary and far-left orientation that was the problem, and his complete rejection of the civic order, not the fact that he spent his free time with atheist Jews. No person believing in civic values would have called communism a “Hebrew swindle”, since the wording basically assumes that the 1919 Council Republic was some kind of swindle that distorted real, valuable content, i.e. a scam; if it had not been led by Jews, it would have been “good”. Babits should have called this “nonsense”, not that Jews exist and that as a people they have a unique Jewish culture. His frail answer that Ady “wasn’t even that Jewish” only proves that, despite his liberalism in theory, Babits had little idea of civic principles.

Ady’s leftism was not a sin for the nationalists who professed nationalist-anti-capitalist ideals: just as Dezsó Szabó was forgiven for his communist articles (‘With what faith he believed, even under a red flag!’[19]) and they were willing to forgive Móricz as well (even if he was a communist, ‘but at least he is Hungarian by blood’[20]), they also accepted Ady’s socialism. Lendvai believed that Ady was a Hungarian genius, ‘even if he had such a tragic and strange fate’,[21] and according to Szózat, ‘Ady was still Hungarian and ours. We take him back. We accept him as a Hungarian not only in the falcon-like flight of his soul, but also in his final downfall’.[22] Zsilinszky also wrote that he respects ‘Ady, the great and beautiful flower of the Hungarian race, even in his disease and sin.’[23] These nationalists blamed Ady’s decadence on the Jews, and thus no one responded to Babits’s excuse that Ady “lived a perfect, beautiful private life”[24] – after all, everyone knew that this was not true.

Ady’s leftism was not a sin for the nationalists who professed nationalist-anti-capitalist ideals

The futile struggle over the dead Ady, which was carried out by the leftists and rightists, was ultimately perhaps best described by the Calvinist journal Kálvinista Szemle, referring to Lendvai’s poem quoted above and Babits’s subsequent reply: ‘Two poets are fighting over Ady’s corpse. One, István Lendvai, is Hungarian and a Christian, the other, Mihály Babits, merely writes in Hungarian and has no faith in God. And they all claim Ady as their own. . . [But] we have little right to object if the journal Nyugat claims Ady for itself. Because no matter how much we try to explain Ady’s sufferings with his patriotism and other things, the sad fact is that this undeniably huge talent that grew out of Calvinist roots lived a derailed life’.[25]

The right-wing criticism of Ady was, of course, extreme – and often stemmed from antisemitic arguments – but there may have been something in the statement – which was written by a reader’s letter addressed to Lendvai – that describing Ady’s radical leftism as some kind of laudable Hungarian patriotism was a “stillborn attempt”.[26]

And finally, again Dezső Szabó established two more important things: on the one hand, how it was pointless on the part of the liberal-conservatives to debate Ady’s talent. When Ferenc Herczeg wrote that there is not a single poem by Ady that is worth reading, even though by “objective standards” he considered Ady “talented”, Szabó replied in his usual bitter tone: “Well, my lord Herczeg, what would you say if a stinking piece of match said this objective sentence: ‘I consider the Sun to be a brightly lit body?’ Look, Ferenc Herczeg, the educated French say about this kind of health: ‘Vous êtes malade [you are sick].’[27]

It is true that Herczeg, in addition to his bourgeois values, was far from being as talented an author as Ady; and that is why perhaps Dezsó Szabó was right again when he wrote in a 1921 editorial that out of the writers attacking Ady, ‘not even 113 counter-revolutionary courses will make a great poet. . . because the value of Hungarian art does not depend on how many times the words “homeland”, “Hungarian” and “Attila” are stuffed into it, but on how specifically the Hungarian spirit is expressed with what absolute artistic values’.[28]

[1] See Jászi’s letter to Ady in 1906, http://mek.oszk.hu/05500/05565/html/al0259.html, accessed: 16th July 2022

[2] Gábor Vermes, ’Tisza István’, Századvég, (1994), 187.

[3] Jenő Rákosi, ’Tiszavirág. Cikkek, levelek, beszédek, 1916-1919’, Budapesti Hírlap, (1920), vol. 2., 541.

[4] Bécsi Magyar Újság, (27 December 1921)

[5] Magyar Helikon, (1921), 571.

[6] Gyula Krúdy, ‘Ady Endre éjszakái’, Nyugat, 1925/3–4.

[7] Salamon Konrád, ’Nemzeti önpusztítás, 1918-1920’, Korona, (2001), 72.; Ady Lajos, ’Ady Endre’, Amicus, (1923), 231–232. See also a statement by the wife of Lajos Ady: Egyedül Vagyunk, (15th January 1943)

[8] See his poems: http://mek.oszk.hu/05500/05552/html/av0121.html, http://mek.oszk.hu/05500/05552/html/av0073.html and http://mek.oszk.hu/00500/00588/html/vers0302.htm, accessed: 16 July 2022. For his collected journalistic articles see: http://mek.oszk.hu/00500/00583/00583.pdf, accessed: 16 July 2022. Quoted pages: 231, 609, 749–750, 735, 1046, 1061, 1126. (on Marxism), 1046. (churches), 749–750. (confiscation).

[9] Dezső Szabó, ‘A forradalmas Ady’, Táltos, (1919), 7.

[10] János Horváth, ‘Aranytól Adyig. Irodalmunk és közönsége’, Pallas, (1921), 38, 47.

[11] Magyarság, (27 March 1921)

[12] Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum (hereinafteras PIM), V.3230., Lendvai to Lajos Ady, (6 October 1920). For the poem see: István Lendvai, ’Köszöntő, 1918-1919’, Táltos, 1920, 35.

[13] Magyarság, (26 July 1927)

[14] Nyugat, 1920/3–4.

[15] Nyugat, 1920/3–4.

[16] Gondolat, (5 October 1919)

[17] Géza Komoróczy (ed), ’Zsidók a magyar társadalomban. Írások az együttélésről, a feszültségekről és az értékekről, 1790-2012′, Kalligram, (2015), vol. 1., 805.

[18] Nyugat, 1920/3–4.

[19] Ifjak Szava, (23 November 1919)

[20] Endre Zsilinszky, ’Nemzeti újjászületés és sajtó’, Táltos, (1920), 96–97.

[21] Papers of István Lendvai (hereinafter PIL), István Lendvai, ‘Mit írtam Ady Endréről?’, manuscript

[22] Szózat, (3 July 1921)

[23] Magyarság, (26 July 1927)

[24] Nyugat, 1920/3–4.

[25] Kálvinista Szemle, (4 April 1920)

[26] PIL

[27] Dezső Szabó, ’Tanulmányok, esszék’, Kortárs, (2007), 243–244.

[28] Zoltán Szőcs (ed), ‘Szabó Dezső vezércikkei a Virradatban’, Szabó Dezső Emléktársaság, (1999), 116.