The city known today as Székesfehérvár, formerly known as solely Fehérvár, has played a greater role in Hungarian history than any other city apart from Budapest itself. Before Buda, before Pozsony, before Visegrád, there was Fehérvár. The history of the city has, for the past millennium, been defined by it most famous son and inhabitant: King Saint Stephen, the first Christian King of Hungary. Following the consolidation of his power, King Stephen established his Royal court in the city and ordered the construction of a Basilica. Fehérvár became the secular and ecclesiastical locus of power in Árpád Hungary, the seat of the court, the home of the great Basilica, the setting of coronations, and the final resting place of rulers and their families. It was also in Fehérvár that, as legend has it, the Saint King dedicated his Crown to the Virgin Mary—an act of Christian and national devotion that would later serve as the legal basis for Hungary’s unique Doctrine of the Holy Crown. For the first centuries of Hungary’s existence as a Christian Kingdom, its history was defined and dictated from the walls of its City of Kings.

Fehérvár was not to last long as the Royal capital, being replaced a few centuries after the death of Saint Stephen for a long succession of cities that began with Visegrád and would culminate in Budapest. Nevertheless, the city of Saint Stephen never lost its importance in the Hungarian imaginaire national. For the Angevin Kings, Fehérvár was a means through which to emphasize their legitimacy and their Hungarianness. For King Matthias Corvinus, it was a means to demonstrate his penchant for greatness and the elegance of his Kingdom and rule, akin to those of older Houses than his. The Basilica was made the physical manifestation of the rulers’ worldviews and intentions. Throughout its 500-year history, it underwent several renovations, increasing in size, changing its dominant architectural style, adapting to the times as the times adapted to Hungary’s position in Europe. This history was cut short by the Ottoman invasion and the wars that ensued, during which the Basilica was reduced to ruins by a combination of the invading Army’s treatment of the building and a devastating fire. With the Royal seat having long left Székesfehérvár, the City of Kings lost its paramount status. The Basilica, notwithstanding its pivotal role in the first five hundred years of Hungarian history in the second millennium, was never to be rebuilt after its final demise in 1601.

Times had moved on, and, with them, the location of the Kingdom’s capital and the site of coronations and Royal burials. The City of Kings, though maintaining its historical importance, had been relegated to the status of a provincial town, overshadowed by the likes of Pozsony and Budapest. Archaeological excavations in the late-19th century brought renewed attention to Székesfehérvár and, specifically, to the site of the old Basilica. The consolidation of a historicist and Christian-inspired Weltanschauung during Hungary’s two decade-long Horthy era further consolidated the city’s place in the collective national memory, not least due to its association with St Stephen. Székesfehérvár saw several monuments to its most illustrious resident rise during this period. A memorial to the lands lost in the Treaty of Trianon, featuring the Holy Crown, was built just outside the city centre. In front of the baroque Bishop’s Palace, an ornate fountain decorated with a sculpted Globus Crucifer evoking that of the Saint King was erected in 1938.

And, just outside the ruins of the Basilica, in a humble but solemn neo-Romanesque style, a new Mausoleum of St Stephen, the ultimate symbol of the Saint King’s paramount position in Hungarian history and his lingering influence 900 years on, was built.

Saint-King and Country

The ruins of the basilica would not see renewed interest until four hundred years after their final destruction, apart from further erosion due to nearby construction as the city developed around them. The 19th century saw a revival of the Hungarian national consciousness, particularly following the 1848 Revolution, the Compromise of 1867 that officially established the Dual Monarchy. Throughout the second half of the 19th century, and especially in the fin-du-siècle, Magyar motifs and themes were ubiquitous in art, literature, and scholarship, and matters of national identity took centre stage in political and intellectual life. A renewed national consciousness was not a Hungarian exclusivity, with most, if not all peoples of Central and Eastern Europe, heretofore under the rule of large, multiethnic Empires, undergoing similar processes of self-(re)discovery. Hungarians, however, had much to draw from, having been a Christian Kingdom for, at the time, over 900 years, and present in the area for centuries before that. Though the Magyar migrations to the Pannonian plains took an important role in Hungarian national consciousness, the cardinal point from which most chose to draw from was St Stephen. And, as often in history, timing played a gentle, if invaluable role in the process. The Hungarian national awakening coincided with the country’s 900 years as a Christian Kingdom. As celebrations were prepared in the Palaces and offices of State in Budapest, and the intellectual elite debated in the city’s gilded cafés, the life of Hungary and the myth of St Stephen were once again, after nearly a millennium, made one and the same.

‘If the Hungarians as a people can trace their roots even before Árpád, Hungary as a State is rooted in the person of the warrior, King, and Saint’

The choice for St Stephen was a logical one. The Saint King was both the founder of the modern Hungarian State—whence modern Hungary drew its legitimacy—and the author of the oath from which the Doctrine of the Holy Crown originated. If the Hungarians as a people can trace their roots even before Árpád, Hungary as a State is rooted in the person of the warrior, King, and Saint who, like many of his descendants, had been buried in the grounds of the now-ruined basilica. Excavations in the site of the Basilica in the late-19th century led to the finding of St Stephen’s sarcophagus, dating from the Romanesque era, and its transfer to the new Hungarian National Museum. The sarcophagus was a major attraction during the celebrations of his Coronation, which underwent in typical Habsburg pomp throughout the city. The entry of Austria–Hungary into the First World War, the end of the Empire, and the imposition upon Hungary of the Treaty of Trianon would mark the most significant shift in the country’s political and historiographical culture in centuries. The Kingdom of Hungary was de jure restored, with Admiral Miklos Horthy as its Regent. Gone was the festive mood of the fin-du-siècle national awakening, permeated as it was by the curves and elegance of Hungarian Secessionism. In came a more solemn and nationalist atmosphere, one where the elevation of the national spirit was linked with two ideas: restoration—of the old Kingdom—and revision—of the Treaty.

In aesthetic and cultural terms, the Horthy era is remembered for its promotion, or even glorification, of national and traditionalist themes, while also harbouring a strong avant-garde scene in and around Budapest. The official, though unwritten Hungarian Weltanschauung of the 1920s and 1930s was strongly based on ideas and values of the old Empire and of the 19th century’s national uprisings, as well as a great degree of Hungarian historicism. The main difference from the previous decades is the revivalist tinge that characterized those very same themes. Hungary was, at that time, a reeling country, one that had undergone unprecedented material and societal destruction following the Great War and the collective traumas of Trianon, the Soviet Republic, the Civil War, and its first period of hyperinflation. For millions of Hungarians, and certainly for those in power at the time, the greatest tragedy was that signed off at the gilded halls of the Parisian palace whose name entered the Magyar language as a synonym of national mourning. And, ultimately, this would be the spark that would set the motion of the Horthy era’s revival of Hungarian nationalism—a nationalism whose hues and nuances would often follow the tragic path Europe embarked on in those turbulent decades.

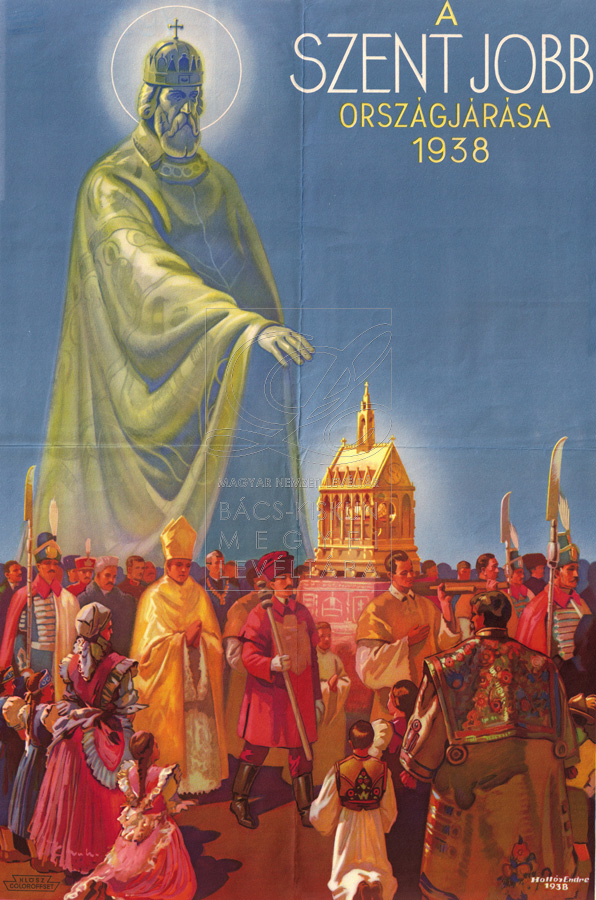

In this national mood of exaltation of a Christian, aristocratic Hungarian Kingdom with a State-building and State-reviving mission, the figure of St Stephen, not least in his own century of 900 years, became even more central. Despite the absence of a King, the Doctrine of the Holy Crown, founded upon the Saint King, retained major importance in Hungarian law, being the subject of fierce academic debates. A major celebration was organised for 1938, the nine-hundredth year Jubilee of the Saint King’s death. The idea, originally proposed by the Archbishop of Esztergom–Budapest, was warmly welcomed by Horthy and Hungary’s Catholic circles, who provided political and financial support thereto. The celebrations, timed to begin as the World Eucharistic Congress, held in Hungary, concluded its works, were intended as much to celebrate the Saint King as to consolidate the image of a strongly Christian, tradition-preserving Hungary.

To commemorate the Saintly King, his most famous relic, the Szent Jobb, the ‘Holy Right Hand’ preserved in the St Stephen’s Basilica of Budapest, travelled the entire country. A special carriage, known as the Golden Train, was made to transport it and allow for public access to the relic in a dignified setting. The high point of the commemorations would be 20 August, when the Procession of the Szent Jobb takes place in Budapest—which, on that year, featured in a boat tour of the relic along the Danube. The homages to St Stephen did not stop at events and processions, however. As the Golden Train crossed the Pannonian plains, works were being finished in a discreet building just outside the ruins in Székesfehérvár. For the first time in centuries, where once rose the centre of royal and Christian power in Hungary, stood a rebuilt Mausoleum of Saint Stephen, carefully crafted in the style of the old Basilica.

Kings among the Ruins

The neo-Romanesque Mausoleum of St Stephen was intended to be, from the outside, as faithful to the original basilica as possible while, on the inside, presenting a pictorial history of St Stephen and of the past 900 years of Hungarian history and of Hungarian Christianity. It was intended as a national and religious monument, where worship of the Saint was carefully combined with reverence to the King—as suits the figure of Saint Stephen. From the outside, it should evoke earlier centuries. From the inside, it was clearly a product of 1938. From its position at the entrance of the ruins of the former Cathedral, the Mausoleum seamlessly merged Catholic reverence and historical deference, carefully messaged for its time—something that would, later, cost it dearly. That mélange is the result of the juxtaposition of the virtuosity of one of Hungary’s most prominent avant-garde painters into the work of a young, gifted architectural restorer. These men were, respectively, Vilmos Aba-Novák and Géza Lux.

‘It should serve…as a Mausoleum and dignified burial site for the Saint King…As such, its style should match, as much as possible, that of the destroyed basilica’

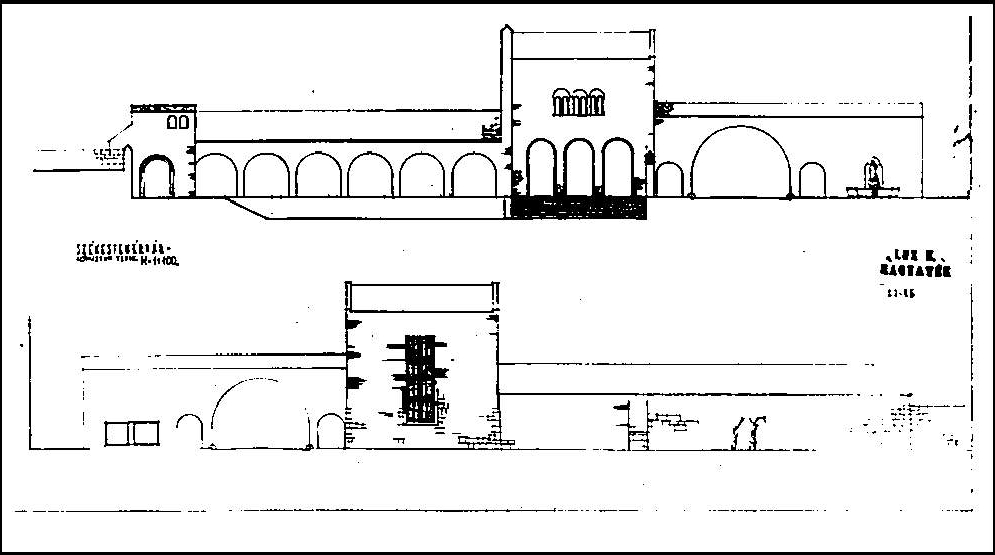

The Mausoleum building is the work of two generations of the Lux family. Géza Lux, the lead architect of the project, is best-known for his work in the restoration of historical buildings across Hungary. Géza Lux followed on the footsteps of his father, Kálmán, known for his work in the restoration churches in Hungary and Transylvania, as well as that of the Visegrád Castle. At the time of his commission, Géza Lux was a young architect and scholar, whose tasking with a project of such grandiosity attested both to the quality of his work and—doubtlessly—to the prestige of his father, who would be expected to actively take part. Lux opted for a simple, neo-Romanesque style for the building. The building was intended to serve a double purpose. It should serve, firstly, as a Mausoleum and dignified burial site for the Saint King, built in time for the celebrations of the 900 years of his death. As such, its style should match, as much as possible, that of the destroyed basilica. The choice for neo-Romanesque was a wise, as well as a pragmatic one. Though the Basilica had been rebuilt several times over the course of its existence, its first incarnation had most certainly been Romanesque. The stylistic choice weaves an aesthetic thread between Lux’s time and that of St. Stephen and fulfils the organizing committee’s desire that the building be ‘unified’ with its surroundings in an ‘architectural, artistic, historical, and emotional’ dimension.

The second purpose of the Mausoleum was for it to be a ‘gate’ to the ruin garden, on which excavations and discoveries had continued throughout the century. A surge in visitors and general interest was expected in 1938, as the memory of the Saint King became the central theme of national celebrations. The Mausoleum’s location at the entrance of the ruin garden is both historically accurate and logistically fortunate. As visitors passed through the Mausoleum and paid homage to the founder of the Hungarian State on their way to the ruins, Lux’s design allowed them to gaze upon the long-lost glory of the Basilica. From the living, restored Mausoleum of a King onto the ruins of the church where his entire dynasty was buried—an ideal aesthetic manifestation of the national self-perception of early 20th century’s Hungary. Eventually, Géza and Kálman Lux would go on to restore the entire perimeter of the ruin garden, including its towers and adjacent buildings. Work on the Mausoleum lasted for two years, finishing in time for the Jubilee celebrations.

The interior of the Mausoleum was richly decorated. In the centre of Lux’s neo-Romanesque building lies the empty Sarcophagus of St Stephen, dating from the 11th century, and until then exhibited at the National Museum. Surrounding it is a series of murals by Vilmos Aba-Novák. The murals depict the history of Hungary through the history of Stephen, as Saint and as King. The mural to the left of the Sarcophagus focuses on his Saintly aspect, and on Hungary’s dimension as a Christian Kingdom. In this panel, the Szent Jobb takes centre stage, depicted giving a Christian blessing while the King’s left hand holds the Globus Cruciger. It is flanked by several major figures of Hungarian Christianity. Saints, Popes, priests, bishops, and warriors, side by side in a procession that transcends time and place, united by their role in consolidating and defending the Christian faith in Hungary, from the baptism of the Hungarian people to the modern era, decorate the wall. A genealogical tree is also depicted, linking Stephen to both his successors and European predecessors such as Charles Martel. The Szent Jobb is itself flanked by two scenes.

To the right of the Sarcophagus, there is a mural centred around the Holy Crown, and dedicated to Stephen’s Kingship. If the Szent Jobb mural depicts the Christian aspect of Horthyite Hungarian Weltanschauung, this one is clearly its historicist counterpart. The mural draws a thread, starting from Saint Stephen, whose coronation is depicted, and ending at Horthy and his Minister of Religion and Education, Bálint Hóman, the main political patron of the Mausoleum. The Holy Crown acts as the unifying element, in line with the Doctrine associated with it. The panels were complemented by elements on the Eastern and Western walls, which spoke to the King’s temporal and spiritual powers—his coronation and the dream of Pope Sylvester II that preceded it are depicted in these spaces. This attests both to Aba-Novák’s intelligent use of the limited available space and to his interpretation of the transcendental nature of said events. Sculptures of traditional motifs, as well as stained glass windows by master glazier Lily Árkaly-Sztehlo, complete the Mausoleum.

The Mausoleum was well-received at the time, not least by Hóman, whose effigy is featured alongside that of Horthy in the Holy Crown panel. It was visited by the Regent, Homán, and other secular and religious dignitaries of the time, with Aba-Novák taking centre stage in these events. The Szent Jobb, so carefully depicted in the Mausoleum’s walls, graced it with its presence in the city. The building would go on to survive the damage wrought by the Second World War in Hungary—a fate that, sadly, was not shared by Géza Lux, who died in an air raid at the young age of 34. During the Communist period, in line with the regime’s anti-religious and anti-historicist policy, the Mausoleum was desecrated and Aba-Novák’s murals whitewashed. Buildings from the Horthy era, or strongly associated with the period, were targeted by the new authorities. It would be only in the 1990s that the building would be reverted to its former glory, with Aba-Novák’s murals restored for the first time. Renovation work was carried out several times in the following decades, and the Mausoleum is once again fit for the double purpose it was once built. Entering the building, one is immersed into the thread woven by Lux and Aba-Novák nearly a century ago. The murals, though anachronistic vis-à-vis the Basilica, serve to situate the Mausoleum in its actual timeframe, while transporting visitors and pilgrims alike to another dimension of Hungarian history.

Nowhere else in Hungary than in this small, neo-Romanesque building is the history of St Stephen and his legacy so well-condensed and so gracefully interwoven into the history of the country that succeeded him—in glories, tragedies, and struggles. Nested in the centre of Székesfehérvár, between its historic centre and a myriad of Communist-era buildings, the Mausoleum contrasts even more strongly with its surroundings than Lux and Aba-Novák could have imagined in 1938. Before seeing it in person, I have asked myself why Hungary had not dedicated a more grandiose and ornate monument to the remains of its founder. It is only when entering the Mausoleum that one truly understands the genius of Lux and Aba-Novák—the juxtaposition of the solemn and the colourful, the historical and the modern, the ruins and what was raised from them. Paying homage to a towering figure is always a herculean task. To do so with limited creative possibilities, for reasons of historical accuracy, is even more so. And yet, Lux, Aba-Novák, and the other artists involved in the project have achieved this masterfully. That this simple building with its Romanesque arches would house the Mausoleum of a great King, and some of the most beautiful murals in the entire country, is more than a virtuous artistic choice.

It is a metaphor for Hungary itself—a nation of immense beauty, history, and faith, if one knows where to look.

Related articles: