The following is an adapted version of an article written by Barnabás Leimeiszter, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

Farkas Molnár, who followed a strange political path, was an important figure in Hungarian modernist architecture. The exhibition, which will be on display at the Janus Pannonius Museum — Modern Hungarian Art Gallery in Pécs until September, presents Molnár’s fine art work.

Magyar Krónika has written several times about the outstanding figure of Hungarian modernist architecture, Farkas Molnár, who was born in 1897 and died in 1945.

Molnár, who worked in Walter Gropius’ office, held left-wing views for most of his career. Together with his ideological and career partner, József Fischer, they dealt a lot with the problem of social housing construction, for which they came up with solutions inspired by Bauhaus and Le Corbusier, such as the plan called Kolház, in which the principle of the family household was pushed into the background and the space was divided between rooms suitable for individual retreat and those serving the collective household.

Architects with an innovative spirit, like Molnár, received few state commissions in Hungary during the Horthy era, so their creative legacy consists mainly of buildings built with private capital. Molnár’s career took a turn around 1938–39, when he began to approach the (far) right, prepared the plans for a cooperative village (Rongyosújfalu) to be built for the soldiers of the Rongyos Gárda (Ragged Guard), and in his articles, he criticized the ‘pseudo-modern’ architecture of Palestine and Újlipótváros, discussing ‘architectural Hebraism’. His last large-scale work before his death was the unfinished Hungarian Holy Land Church in Hűvösvölgy.

In 1940 construction began at the request of Franciscan monk Mór Majsai, who had visited Palestine and was appointed as the Holy Land Commissioner. Farkas Molnár was given a challenging task: ‘he had to design a huge space by organizing the scale copies of 21 holy places into a unified composition, which would evoke the Holy Land environment for the faithful’. The external works were scheduled to be completed in 1950, but the war and then the communist takeover interrupted the work, although the completed parts of the building did not suffer any severe damage during the fighting.

Tractor factory warehouses were placed in the torso of the church, and then the offices of the Metropolitan Archives operated there until 2004. After that, the Holy Land Church was granted protection as a monument, and a new function is still being sought for it. However, the decaying building preserves a kind of dignified resistance to plans born with a complete denial of the basic concept.

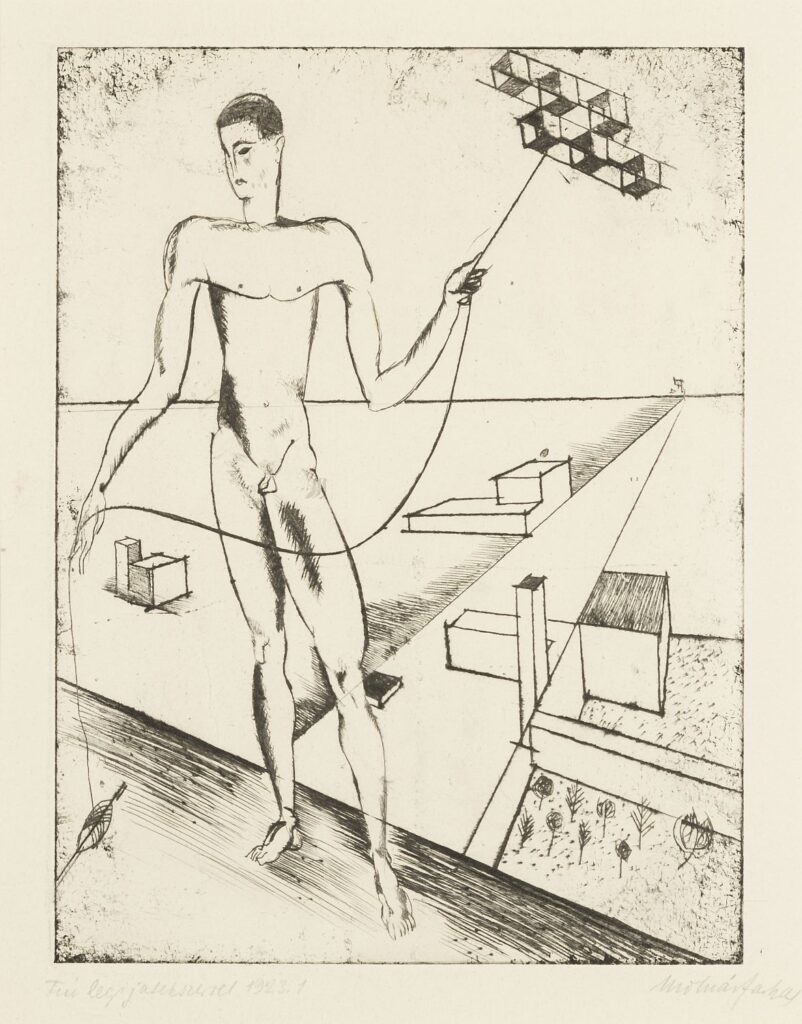

‘The recurring motif of his paintings, reminiscent of his childhood games with his siblings and the Bauhaus kite festivals, is a…“flying toy”’

Farkas Molnár is primarily known for his architectural work. However, the exhibition Boy with a Flying Toy — Artist Farkas Molnár, which will be on display until 21 September at the Janus Pannonius Museum — Modern Hungarian Art Gallery in Pécs, focuses on the early stages of his career.

Between 1918 and 1921, Molnár interrupted his architectural studies in his hometown of Pécs, which was occupied by the Serbs, and then from 1921 to 1924 in Weimar, where he worked as an associate in Gropius’s architectural office. He sought opportunities for self-expression as a visual artist, connecting with the avant-garde experiments of the era (Bauhaus, Dadaism, Constructivism). The cubist-inspired drawings and paintings, capturing the impressions of his trips to Dalmatia in 1918 and Italy in 1921, all reflect the architect’s perspective.

The recurring motif of his paintings, reminiscent of his childhood games with his siblings and the Bauhaus kite festivals, is a—what a beautiful term—‘flying toy’, a flying model, a symbol of longing, separation, and at the same time a Promethean innovation that revolutionizes everyday life.

Nudes were also a favourite artistic theme of his: perhaps the most spectacular piece of this line of his artistic work is the 1921 painting Lamentation, which places a naked man and woman in the environment of the classic Pietà scene, bringing together Christian and pagan tradition. It is striking that his works are always organized around two poles, presenting the contrast of engineering design and arrangement and natural existence, which would be resolved into harmony by the avant-garde revolution of life, the arrival of the ‘new Arcadia’.

In the first issue of the Krónika magazine of Pécs, he himself stated: ‘As in the classical era of art, nude compositions reappear, representing the pinnacle of painting, what impressionism could never reach, the knowledge of dealing with nudes, the higher art of creating new human types.’

The work that gives the exhibition its title is the best example of this utopian reverie that combines tradition and modernity: a slender, naked boy flies his flying toy into the sky on a string, with a few scrawls of woos, building blocks, and a road running into infinity in the background. He also used and varied these motifs in other works (Nude Architecture [Male Back Nude with Villa Plan and Airplane], 1923; Two Nudes, 1923; Lovers [Georg and El Muche at the Haus am Horn], 1923; Study Area, Man with Cactus and Airplane, 1924). He plays on this duality even more clearly in the drawing that shows a robot courting a young woman (Machine Man [A Mechanical Man Seduces a Woman], 1923).

The painting ‘Proposal (Street)’ from 1923 offers exciting possibilities for interpretation: on the side of a modernist apartment building, a naked man kneels before a woman, whose posture suggests restraint, or even terror, and whose lower body is strangely flowing; a young fancy man follows the scene from the background.

The Man with a Building (1923–24) is also an impressive and memorable work: on a jagged waterfront, a man with an almost arrogant expression but a strangely shy posture—perhaps the artist himself?—stands, the colour of his clothes rhyming with the redness of the mysteriously functional brickwork extending above the water.

In the mid-20s, Molnár slowly turned away from fine arts. However, his fine arts and architectural work are closely intertwined. As the exhibition highlights regarding his architectural linoleum engravings, which are difficult to classify in terms of genre: ‘The choice of…a bird’s-eye view—mostly axonometric—perspective may be related to the top-down perspective of the “flying toys” that he loved in his childhood.’ At the end of the exhibition, we can see his collages that combine the rigor of architectural plans with the extravagant playfulness of Dadaism.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.