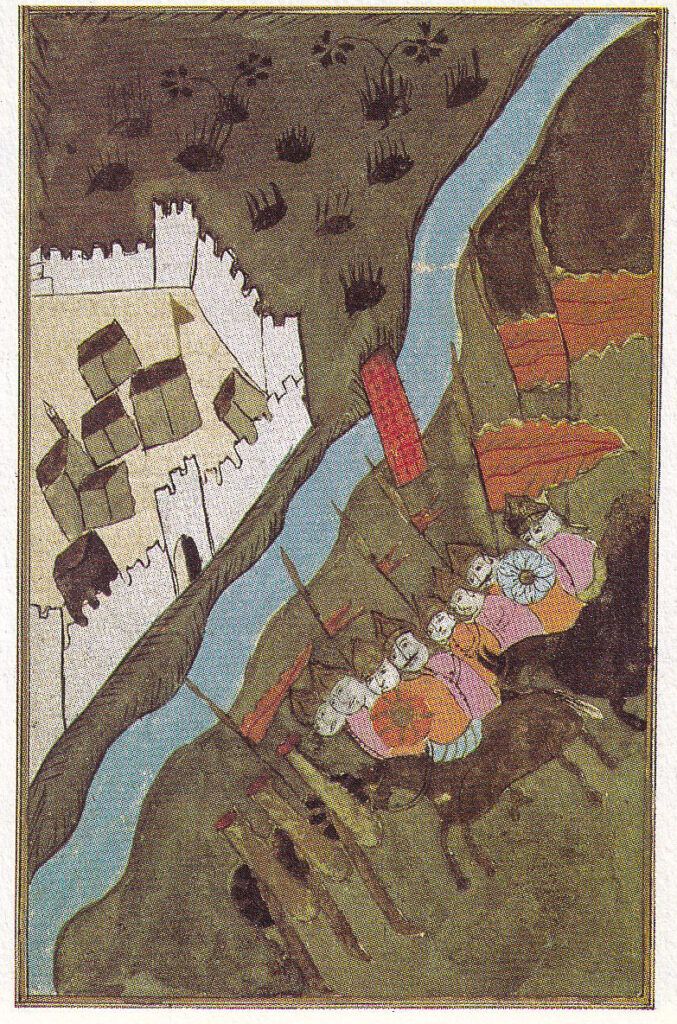

The castle of Szabács (today’s Šabac, Serbia) was built by the Ottomans in 1471/72, 50 kilometres west of Belgrade on the right bank of the Sava River. The castle, well-fortified with artillery, was made virtually impregnable by the marshy terrain surrounding it and the water of the Sava River flowing into the castle’s moat. The castle was small in size and seemingly insignificant, but King Matthias of Hungary (r. 1458–1490) recognized its strategic importance, as there were no other Hungarian border fortresses on the right bank of the Danube and Sava except for Belgrade at the time. This explains why Matthias launched an unprecedented attack against it at the end of 1475.

The king was right, as in 1521, the castle of Szabács could have stopped the Turks who were setting out to capture Belgrade. But it did not happen this way. The fall of the castles of Szabács and Belgrade directly led to the tragedy of Mohács in 1526 and the fall of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. If Szabács had been able to resist in 1521, the course of medieval Hungarian history would have been completely different.

Matthias’ anti-Turkish policy attracted international attention already during his lifetime. According to historians, Matthias was one of the most outstanding strategists of his age, who was able to achieve the maximum with the means and forces at his disposal. He correctly recognized that there was no necessary or close connection between politics and actual military action. Political alliances and the establishment of defensive lines can achieve at least as much as bloody battles. With his famous mercenary army, the so-called Black Army, Matthias was able to pose a strategic threat to the Turks, leading it into battle against them only once, during the siege of the Szabács Castle. It is no coincidence that, following in the footsteps of King Sigismund of Hungary (r. 1387–1437), Matthias continued to build and strengthen the southern borderline. Keeping a permanent mercenary army in arms had such a deterrent effect on the Turkish power that it did not undertake any serious attacks.

‘The fall of the castles of Szabács and Belgrade directly led to the tragedy of Mohács in 1526 and the fall of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary’

After 1474, the Hungarian king was forced to take action. Ali, the Ottoman pasha of Szendrő (today’s Smederevo, Serbia), took advantage of the Hungarian king’s war in Silesia in February 1474 to invade the country and plunder one of the richest cities of the Hungarian Kingdom at the time, Várad (today’s Oradea, Romania). He left with many thousands of prisoners; then, at the end of the year, they also invaded the principality of Stephen the Great (Ștefan cel Mare, r. 1457–1504), voivode of Moldavia. Hungarian assistance was not long in coming, and with help from Transylvania and Poland, the Moldavian voivode defeated the invading Turkish troops at Vaslui in January 1475 and pledged his allegiance to King Matthias again in the middle of the year. The Turkish attacks provided Matthias with an opportunity to become actively and spectacularly involved in the Venetian–Turkish war, which had resumed in 1464 and had been made relevant by the repeated Turkish sieges of Scutari (today’s Shkodër, Albania) on the Adriatic coast.

In 1475, the king waited for autumn with excellent tactical timing, when he summoned his troops to avoid encountering the main Ottoman army, and it was easier to obtain supplies after the harvest. He advanced remarkably slowly towards the southern border, staying in Szeged on 25 October, Tolna on 2 November, and Mohács on 5 November. He marched with a huge army to capture the castle, estimated by modern researchers to number between 10,000 and 15,000 men. He took with him the best units of his mercenary army, including Hungarian, Szekler, German, and Czech mercenaries, as well as Serbian auxiliary troops. On 18 November, a letter was sent from the army stating that the king’s ship had joined the fleet heading south on the Danube. According to this, the Hungarian army took advantage of the river, and both the soldiers and some of the equipment reached the battlefield by water. Sources mention a hundred ships and a thousand carts. The king spent Christmas in the castle of Belgrade. In view of the coming winter months, they had to take serious supplies with them, and, anticipating the cold, he also had coats made for the soldiers. The crossing of the Sava and the landing were one of the most critical points of the campaign, which the king secured by setting up a mobile wooden fort reinforced with firearms.

It is not entirely clear why the march between October and January 1476, when the siege began, was so slow. Perhaps the explanation is that it left the Turks in uncertainty as to whether Moldavia, Wallachia, or Serbia would be the target of the campaign.[1]

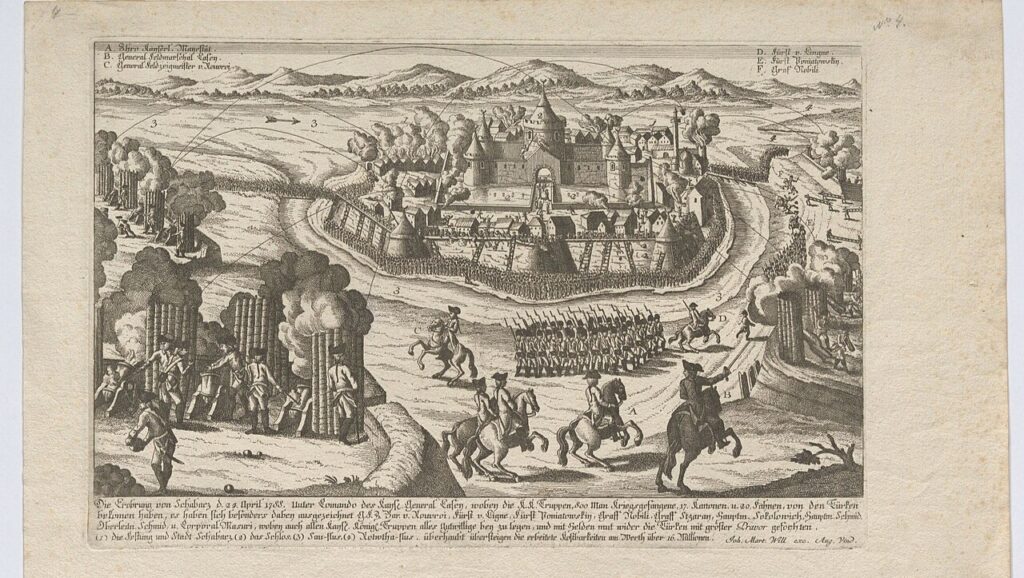

Numerous contemporary accounts of the siege have survived. Hartmann Schedel’s printed chronicle of the time makes the siege of Szabács one of the most detailed events in Hungarian history. The 600-page chronicle was published in 1493 in Nuremberg, one of the centres of German trade and book publishing, in German and Latin. Matthias’ propaganda thus achieved its goal most perfectly, as dozens of German and Latin editions of the chronicle informed the world about the Hungarian victory. The chronicle is known in Hungary for its realistic engraving of the city of Buda, although it also features a large (23×24 cm) realistic engraving of the castle of Szabács. We can rightly assume that the model for this was an illustrated leaflet commissioned by King Matthias to report on the event. Szabács remained unparalleled in Hungarian historical memory, as the siege of 1475–76 is the subject of the earliest historical song in Hungarian, which was written around the time of the events. The manuscript was discovered as early as 1871, but its authenticity has been debated by literary historians until recently. It has now been decided that its surprising linguistic turns of phrase can be explained by the fact that the unknown author, who presumably took part in the siege himself, was not Hungarian, but possibly a German mercenary whose mother tongue was Hungarian. As with his previous successes, Matthias made the most of the propaganda opportunities offered by the victory. Not only in the country, but also in Rome and Venice, gratitude was offered in church processions, the Pope and the Venetian ambassadors sent their congratulations, and aid against the Turks continued to be provided as well.

‘Dozens of German and Latin editions of the chronicle informed the world about the Hungarian victory’

The siege lasted a long time and was extremely difficult, with the castle surrendering on 15 February after 33 days. This was partly due to the low water level of the Sava River and the ice, which prevented the use of ships in the siege. The castle walls were made of huge oak beams, reinforced with thick wattle covered with earth-filled clay. The attackers were probably surprised at how difficult it was to break through the earthen ramparts with cannons, as the impact of the projectiles was absorbed by the ground. When the Turkish defenders lost hope of the arrival of a relief army, they eventually surrendered as a result of negotiations.

The Hungarians who entered the castle found 500 Turkish dead, and 700 men and 160 women fit for battle among the survivors. The Hungarian king took many of the Turks into his service. The Turkish prisoners who were released fared worse, as the sultan, in his anger, had them drowned with stones tied around their necks. Hungarian losses were also significant, with one of the king’s favourite Czech mercenary commanders losing his life. As a sign of respect, he was buried in the pantheon of Hungarian kings in Székesfehérvár.

The Turks had already attempted to capture Belgrade and Sabac in 1492, but the southern border defences successfully repelled the attempt. However, in 1521, they were unsuccessful. The Ottoman siege lasted from 4 to 7 July 1521. It is difficult to explain the brevity of the siege, given that in 1476 the castle had resisted Hungarian attacks for a month. In addition to supply problems and the morale of the defenders, advances in siege technology may also have played a role. Later, during the Austro–Turkish War of 1788–1791, Austrian General Anton Ferdinand Mittrowsky recaptured it even more quickly, in a three-day siege in April 1788. Sources tell us that in 1521, the supreme military commanders, the bans, responsible for the defence of Szabács, were not in the castle; the defending army of about 500 men was led by their deputies. At that time, there were no large cannons in the castle, and gunpowder and food supplies were also scarce. When the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent arrived at Szabács on 8 July 1521, the castle was already in Turkish hands. The sultan recognized the strategic advantages of the castle and wanted to march directly against Buda. By 18 July, they had built a bridge over the river, but it was destroyed by a storm. They then marched on Belgrade instead of Buda. Later, the Hungarian Diet discussed punishing the guilty bans, but they were eventually acquitted in 1523.

The siege of 1476 is considered one of the most significant successes in Hungarian military history, enriching the Hungarian border fortification system with a medium-strength fortification that could be held for decades. The Hungarian armies did not conquer any more significant strongholds until the tragedy of Mohács (1526), and its possession provided an important river crossing for the Hungarian border fortification system until 1521. In an international context, however, the victory at Szabács only temporarily slowed down the Ottoman advance in the Balkans, which foreshadowed the collapse of the fragile military balance that had been established.

‘The victory at Szabács only temporarily slowed down the Ottoman advance in the Balkans’

On the Black Sea, the Genoese city of Kaffa (Feodosiya) surrendered in June 1475, and the Crimean Tatar khan became a Turkish vassal. These events finally culminated in 1478–79, when in May 1478 the Turks once again laid siege to Scutari, with the sultan himself present for a time. Despite several attempts, Venice was unable to send relief troops to the castle, which, after more than six months of siege, surrendered in January 1479, leading to peace in February of that year, ending the 16-year Venetian–Turkish war.

Matthias did not personally participate in the aforementioned military events, but the Hungarian court cannot be accused of inaction or neglecting the Turkish front. The military events had varying outcomes, but in a series of battles that tended to favour the Ottomans, the victory at Szabács was of great significance, which was further enhanced by subsequent developments. The siege of the castle also foreshadowed the change in military tactics that would become common throughout Europe in the following decades, in terms of firepower and fortification architecture: the siege of castles built on flat terrain but with modern military engineering knowledge presented the besiegers with new tasks that were unknown in earlier times. The Hungarian army got a taste of this at Szabács.

[1] László Veszprémy, ‘Szabács ostroma (1475–1476)’ [The siege of Šabac], Hadtörténelmi Közlemények, Vol. 122, 2009, pp. 36–61.; Nenad Obradovic, ‘The Siege of Šabac in 1476’, Istorijski časopis/The Historical Review, Vol. 72, 2023, pp. 237–279.

Related articles: