Niccolò Machiavelli, for good or for bad, is undoubtedly the most contemporary iconic figure to be associated with politics. Recognised as the father of modern political science by numerous historians and political scientists, he has been stigmatised as an atheist and an immoral cynic whose writings justified and encouraged oppressive autocracies.

In fact, ‘Machiavelli’s political thought’, as Berkeley University Professor Albert Russell Ascoli said, ‘places us at the very top of the intellectual an ethical “slippery slope” one hears so much about—that is, in the world of politics, society, and culture no longer grounded in secret truth or moral imperatives, no longer able to count on long-cherished principles of order and understanding.’[1]

His ill repute is primarily due to his posthumous publication The Prince[2] (1532), written in 1513, where he explains how the princeps—a single ruler of the state—acquires and holds onto power by craftiness and deceit. This made the term Machiavellian emblematic, but in reality, he never approved of political expediency above morality. In fact, taking a closer look at Machiavelli one sees that he did not de facto create “the slippery slope”, or at least he never intended to do so.

Machiavelli as Second Chancellor

Machiavelli was born in Florence on 3 May 1469, and at a young age became a student of a renowned Latinist, Paolo da Ronciglione. It is believed that he attended the University of Florence, and even a cursory glance at his corpus discloses that he received an excellent humanist education. His first involvement in politics occurs in 1498.

It was the same year that the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola–referred to as the disarmed prophet by Machiavelli–who effectively governed the city as a theocracy, was deposed and executed by his opponents. Prior to Savonarola’s rise, the Republic of Florence had been governed by the Medici family until they and their associates were expelled from the city in 1494. Having ousted Savonarola’s remaining supporters from government positions, the city council elected Machiavelli, despite being privy of any experience in government, as the Second Chancellor of the Republic of Florence.

The chancellors of Florence were effectively the custodians of the fundamental rules of the Florentine reggimento. They formed a nucleus of continuity within a governmental system otherwise operated predominantly by amateurs who were sometimes holding their magistracies for the first time and for a period of no more than six months. It was their task to produce acts of authority on behalf of the ruling establishment with questionable legitimacy and partial autonomy.[3]

The Council of Ten often tasked Machiavelli as their Secretary with relevant and delicate diplomatic and military assignments

After the reform implemented by Chancellor Bartolomeo Scala in 1483, the offices of the First and Second Chancellors were clearly distinguished; the latter had already been established in 1437 for the processing of administrative correspondence with the Florentine dominion and gave the right to the title of Secretary, which then remained over the centuries as the eponym of Machiavelli.[4] And, whenever Florence was troubled not only by internal struggles or by the wars in Italy, the Council of Ten often tasked Machiavelli as their Secretary with relevant and delicate diplomatic and military assignments.

In 1512, Giovanni de’ Medici—who later became Pope Leo X—reconquered Florence, which permitted his family to reclaim the reins of government. Machiavelli was imprisoned and tortured by the Medicis the year after, on suspicion of conspiracy to overthrow the family. After his release the same year, he was forced to retire to his country house in San Casciano Val di Pesa (fifteen kilometres southwest of the city). It was there over the next fourteen years that he composed The Prince and other groundbreaking masterpieces.

Understanding Machiavelli

Reading and understanding Machiavelli can at times be a conundrum because his works at times both complement and contradict each other.

If one does a Google search on Niccolò Machiavelli, websites such as history.com immediately pop up, referencing The Prince—as if it were to be his only contribution—with egregious explanations, such as ‘According to Machiavelli, the ends always justify the means – no matter how cruel, calculating or immoral those means might be,’ or ‘Machiavelli’s guide to power was revolutionary in that it described how powerful people succeeded–as he saw it–rather than as one imagined a leader should operate.’

The former Second Chancellor does seem to provide practical advice to whoever is in authority. He writes, for example, on how imperative it is to familiarise oneself with notable and virtuous men spoken of in the Classical texts, specifically their military operations, such as Julius Caesar.

Machiavelli’s concept of virtue is different from the Christian understanding of the idea. It is rather a political quality where the end is not the afterlife, but the earthly homeland. This very unscrupulous conception of political action, that most certainly would be condemned by Christian ethics (to which the name of Machiavelli will be peculiarly linked in the following centuries) is particularly exposed in reference to those who intend to establish a new state.

In order to achieve that, one must use his strength and ability without any scruples, even if it means being brutal and false towards others, as explained by Machiavelli in Chapter 8 of The Prince. In the chapter he details how Agathocles of Sicily became ruler of Syracuse and enjoyed a long and successful career based upon brutality and treachery. Such reference may be due to the fact that Machiavelli saw the Republic of Florence fall apart because the men entrusted with its liberties did not know how to fight for them. Yet within the same chapter, he forewarns:

‘It cannot be called virtue to kill one’s fellow-citizens, betray one’s friends, to be without faith, without pity, and without religion; by these methods one may indeed gain power, but not glory.’[5]

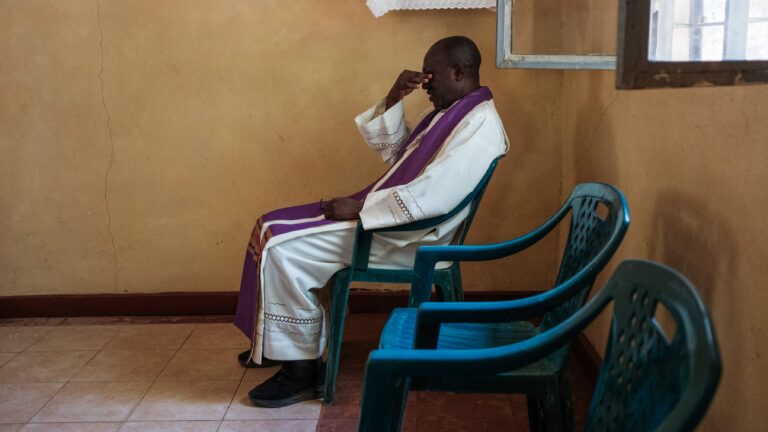

Those who have villanised the Second Chancellor may be shocked to learn that his missives reflected concern and tutelage for the welfare of human beings. While using harsh reproaches, he often recommended to administrators of the Republic to use ‘prudence’, ‘diligence’, do ‘everything thoughtfully and with mature advice’, and to ‘ponder everything and leave nothing behind for which man can live safe’.[6] There are also his orations, such as his remarkable Moral Discourse delivered to the priests and members of the Florentine confraternities (c. 1504), in which he highlights the wrongfulness of sin and the merit of observing penance and practicing charity:

‘Therefore, penance is the only remedy to cancel out evil, all the errors of man, which are many and committed in various ways that can nevertheless be divided into two parts. One is to be ungrateful to God, the other is to be an enemy with your neighbour…. Those who are enemies of their neighbours lack of charity. This, Fathers and my brethren, is what counts most above every other virtue of man, this is which, or the Church of God has always spoken about, he who does not have charity has nothing.’ [7]

The Prince, like his other works, must first and foremost be understood in the context of the historical circumstances of the political fragmentation of Italy when countless kingdoms and cities were under threat of external attacks. The Prince is not a set of guidelines per se as to how the princeps should govern. As he explains to his friend, the Florentine Ambassador to the Roman Pontiff Francesco Vettori, in a letter of 10 December 1513, his purpose in composing it was to consider and ‘[discuss] what is a principality, why types they are, how they are gained, how they are kept, why they are lost.’

Equally important is the context of Machiavelli wanting to reassert himself with the Medici family, specifically to convince them that because of his knowledge of ancient history and his pragmatic experience as a diplomat he should be their emissary, a sort of a go-between in governmental affairs. He simultaneously sought, with a sense of irony, to expose the corruption and tragedy of those who have positions of power, civil and ecclesiastical alike. This is why, despite being a literary humanist, Machiavelli wrote The Prince, similarly to a number of other pieces, in Italian and not in Latin, since the average person did not read the latter.

He sought to expose the corruption and tragedy of those who have positions of power

His ample and varied works describe a ‘world [that] was always inhabited in some manner by men who always had the same passions.’ [8] Given his pessimistic view of man, in addition to his personal sensitivity, he tried to relate, as with his satirical play La Mandragola, the perils of historical world contingency, where man’s intentions are hardly ever honourable and where justice is often an appeasement or a shallow spectacle to gratify the crowd.

The poet and historian Alessandro Manzoni (1785-1783), who also served as Senator of the Kingdom of Italy, said:

‘Machiavelli did not want injustice, whether cunning or violent, as a means, neither unique nor primary, for the proposed ends. He wanted utility, and he wanted it either with justice, or with injustice, pending on the different cases required. Such an ugly mixture in the writings of such great ingenuity came from having put utility in the supreme place that belongs to justice.’ [9]

He can certainly be considered an enigma, because in the end he never tells the reader what his opinions are on what he wrote. Instead, he observes and studies through the facts (the actual truth) the methods and the institutions of politics – and in doing that, he is more of a politologist than a political scientist.

‘Machiavelli renders,’ as Manzoni says elsewhere, ‘a lucid, concrete and precise vision of the political reality, but without any moral inspiration.’[10] His illustrious biographer Roberto Ridolfi presents him as a Christian who did not have a misanthropic view of man, but a realistic one. In like manner, as a Catholic brother recently told me in a sarcastic manner: ‘I have doubts as to Machiavelli’s faith in God. But one thing is certain, he had no faith in man!”

This is why in order to better understand Machiavelli, one should not, as already indicated, just read The Prince. One must examine all of his works, and do so specifically within the context of the socio-political times he lived in.

[1] Peter Constantine (ed.), The Essential Writings of Machiavelli, New York, Modern Library, 2007, p. xiv.

[2] The original title was On Principalities. His usage of the term “Prince” refers to the Roman usage of princeps, which meant “first citizen”; first used by Caesar Augustus in 27 BC. The title was used thereafter by every emperor up to Diocletian (r. 284–305 AD).

[3] Isabella Lazzarini, ‘Records, Politics and Diplomacy: Secretaries and Chanceries in Renaissance Italy (1350–c. 1520)’, in Secretaries and Statecraft in the Early Modern World, ed. by Paul M. Dover, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2016, p. 17.

[4] Gennaro Maria Barbuto, Machiavelli, Roma, Salerno Editrice, p. 42.

[5] ‘Il Principe’, in Opere di Niccolò Machiavelli, Tomo VI, pp. 263-4.

[6] Machiavelli, p. 43.

[7] ‘Discorso Morale’, in Opere di Niccolò Machiavelli, Tomo VI. 1799, pp. 89, 93.

[8] Roberto Ridolfi, La vita di Niccolò Machiavelli, Roma, Castelvecchi, 2014, p. 123.

[9] Andrea Drigani, ‘Machiavelli con gli occhi di Manzoni,’ in Il Portolano, N. 74-75. Florence July-December, 2013, 29.

[10] ‘Machiavelli con gli occhi di Manzoni,’ p. 30.