When people think of Europeans migrating abroad, they often imagine sunny destinations with Mediterranean beaches in Southern Europe. Indeed, countries such as Portugal and Spain remain very popular. Yet for my fellow Dutch countrymen, Hungary is increasingly becoming a preferred destination as well. This must be for different reasons, as Hungary—being landlocked—is hardly known for its beaches.

They are looking for what I would call ‘the old Europe’. Although all European countries have their own distinct history, traditions and cultures, they also share deeper values that can broadly be described as European or Western. Unlike the EU’s vision of Europe, these are not based on abstract progressive ideals, but on lived experience—shaped by history, Christianity, and Greek and Roman thought.

The Netherlands and the Loss of What Was Built

It pains me to say that the Netherlands, like much of Western Europe, is rapidly dismantling what was built over centuries. Uncontrolled mass migration, an aggressive focus on ‘net zero’ climate policies, and the erosion of national sovereignty—while acting as one of the most loyal foot soldiers of the EU’s progressive European Commission—all contribute to this process. Some Dutch citizens have tried to resist this trend.

One of the most crucial figures in this resistance was Pim Fortuyn, a politician who was able to bridge the gap between Dutch cities and rural areas, highly and lowly educated people, and young and old, while representing the sense that Dutch society needed to be protected. Or, as Fortuyn phrased it: ‘Look, what I want, and that seems to be very right-wing according to the left-wing establishment, is not to flush away in a few decades what has been built up here over centuries. I want to preserve this country.’

‘After Fortuyn was murdered by a radical left-wing animal activist…the hope of a generation was shattered’

After Fortuyn was murdered by a radical left-wing animal activist named Volkert van der Graaf, just nine days before the election that most likely would have made him prime minister of the Netherlands, the hope of a generation was shattered. To be honest, nobody has since been able to fill the void Fortuyn left, politically speaking, in the Netherlands. And what Fortuyn warned against has mostly happened.

From Resistance to Leaving the Country

This has led Dutch people who value a more traditional way of life either to form new communities within the Netherlands or increasingly to seek a new home somewhere else.

That ‘somewhere else’ has increasingly been found in Hungary, as Dutch migration to the country has risen steadily over the past two decades. In 2001, 321 Dutch citizens lived in Hungary. In 2024, two decades later, this number had already grown to 3,848. In 2004, 71 people migrated from the Netherlands to Hungary. In 2024 alone, 459 people emigrated from the Netherlands to Hungary, making it one of the top 25 most popular emigration destinations for Dutch people.

Unlike most mass migration into Europe—or even migration from Eastern to Western Europe—this form of movement is not primarily driven by economic or labour motives. This newer trend, often called ‘lifestyle migration’, involves Dutch people seeking a cultural change.

Additionally, the areas where Dutch immigrants settle in Hungary have also changed. Whereas earlier migrants primarily settled in Budapest, many now move to more rural areas, such as villages in Southern Transdanubia.

Quality of Life, Meaning, and Alienation

According to scientific literature, dissatisfaction with public facilities such as housing, high population density, and crime, increasingly exacerbated by mass migration, has been a primary factor in lifestyle migration to Hungary. This is summarized as follows: ‘emigration from high-income countries such as the Netherlands is primarily driven by a desire to enhance quality of life rather than economic gain.’ Or, as I would put it, people recognize that economic success matters, but it is only meaningful in a country where they can share their wealth.

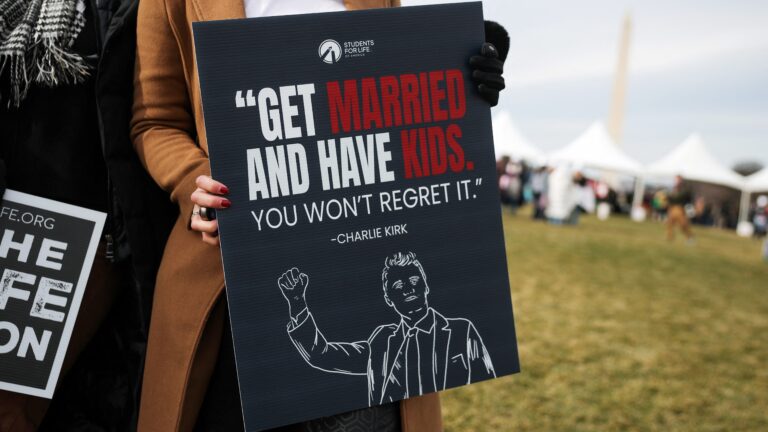

The ‘greed is good’ era of the 1990s seems to be fading slowly, as people increasingly realize that meaning, family, and community cannot be replaced by short-term hedonistic distractions or even by comfort alone.

‘Many people in the Netherlands increasingly feel alienated from their own country’

Thus, many people in the Netherlands increasingly feel alienated from their own country. National traditions—such as Sinterklaas, one of the nation’s most cherished customs—as well as classical Christian holidays like Christmas and Easter, and even a positive connection with Dutch history, have been undermined by progressive activism and the growing influence of Islam in the public and cultural sphere.

Public opinion on these issues does not seem to result in actual change. For example, 80 per cent of Dutch people want less asylum migration. This even includes left-wing voters, as 85 per cent of voters of the Socialist Party (SP) and 52 per cent of voters of the Party for the Animals (PvdD) agree. Yet, mass migration continues all the same.

Stories of Dutch People in Hungary

As part of the largest conservative news platform in the Netherlands, NieuwRechts, we interviewed several Dutch people to ask them what moved them to Hungary and see if these assumptions hold up in practice. As it turns out, this has strongly been the case.

One of them, a former entrepreneur1 from the Noord-Brabant region, has lived in northern Hungary since 2021. His primary reason for moving to Hungary is that its conservative society takes freedom much more seriously and creates stronger social cohesion. ‘During the coronavirus pandemic, I realized that freedom in the Netherlands was conditional. In Hungary, the rules were much less strict, and people here didn’t seem so afraid of each other.’

This relates to how conservatism in the modern sense has been eloquently articulated by Edmund Burke. He recognized that anti-conservative modernism and liberalism erode families and communities, thereby atomizing people. Atomized individuals then become fragile and increasingly look for a new ‘father’ and ‘community’, often found in the state. This is something that is increasingly visible in the Netherlands.

As a result, Dutch people have become lonelier and more fragile, and increasingly look to the state to solve their problems. Or, as Dutch media personality Jort Kelder put it: ‘Dutch people are addicted to the state.’

Freedom, Community, and Education

This also resonates with what the Dutch entrepreneur said about his experience in Hungary. ‘The Hungarian government interferes much less in your daily life here. Fewer rules, less bureaucracy. I’m not afraid to say what I think here, even though the media in the Netherlands talks about censorship in Hungary. In practice, I don’t notice any of that.’

Another aspect of conservative Hungarian society that has become increasingly rare in the Netherlands is strong local community life. A woman we interviewed, who lives in the countryside south of Lake Balaton, shared her experience: ‘I was welcomed here with open arms. The neighbours helped renovate my house, simply because I had moved in. Without expecting anything in return.’

‘Another aspect of conservative Hungarian society that has become increasingly rare in the Netherlands is strong local community life’

She directly related this to Hungary’s more conservative and less individualistic society. ‘There is still a sense of community here. Children walk to school on their own. Older people are not left to fend for themselves. And yes, the norms are more conservative—but that doesn’t make life any less pleasant. On the contrary.’

Another way the difference in conservatism is experienced is through the ‘culture wars’. In the Netherlands, woke ideology remains prominent, with gender-neutral language, rainbow crossings, and a broader anti-Western sentiment. The Dutch entrepreneur emphasized the stark contrast with Hungary, particularly in education. ‘The elementary school here is strict, classroom-based, but structured. Children learn discipline and basic skills. No ideological nonsense or lessons in activism.’

This has become increasingly important, as Article 23 of the Dutch Constitution, which protects the right of parents, particularly Christian parents, to provide education aligned with their beliefs, has come under growing pressure from progressives due to a clash in views on issues such as homosexuality in conservative Christian schools compared to more secular and progressive state schools.

A journalist who also moved to Hungary recognized the same pattern. ‘Woke discussions are hardly present here. There is much less victimhood. People are proud of their culture, without apologizing for it.’ According to him, this does not mean Hungary is without problems. ‘But the discussion is conducted differently here. Less emotionally, less politically correct. There is room to say that you stand for traditional values without immediately being dismissed as “far-right”.’

As much as it saddens me as a Dutchman, the Netherlands is becoming increasingly hostile to traditional and conservative values and ways of living. It is therefore understandable that more people are emigrating from the Netherlands to Hungary.

This may offer a solution for some, but it remains important for conservatives in the Netherlands to stay resilient, to learn from the experiences of their compatriots in Hungary, and to let those experiences inspire conservative communities and political movements back home.

- Due to the negativity surrounding Hungary’s conservative politics, they all decided to remain anonymous. ↩︎

Related articles: