Due to her diplomat husband’s assignment, Viktória Nagyváthy and her family first spent four years in Japan, then, after six years spent back in Hungary, they returned in 2019 and have been living there ever since. In 2020, she founded a Hungarian weekend school in Tokyo, the first and only in Japan. At this year’s Hungarian Diaspora Council meeting in Budapest, she was mentioned several times as a curiosity, which prompted me to reach out and interview her about Hungarians living on the other side of the world.

***

You’ve lived at the ‘end of the world’ before, so let’s start with that period.

We first moved to Tokyo in 2009 through my husband’s foreign service posting, for four years. At that time, our children were only one and two and a half years old. Yes, it really is almost the end of the world, although we could have gone even farther. In any case, when the opportunity arose, we decided to take it and explore the country. I managed to integrate and make friends fairly quickly, but it was a tough four years that we had to survive with two little kids. The Japanese aren’t particularly welcoming; as a European, it isn’t easy to gain a foothold here.

There was a long period in Japanese history, when the country was completely closed off, barely letting in even representatives of neighboring peoples, and Europeans in particular were strongly disliked. Christianity was persecuted, and there were even executions… This closed attitude has somewhat remained; even today, they only allow in people who either possess particular knowledge that benefits the country, or who are willing to do manual labor that locals don’t want to do anymore. These are the two extremes—there is very little middle ground. Of course, this kind of national protectionist attitude is relatively easy for them to exercise: the country is far from everything and is surrounded by the sea.

We returned to Hungary when our daughter reached school age. We spent six years at home, during which time I taught. Then the opportunity came again, but by then we more or less knew what to expect. We came again for four years, but in the end, we stayed longer. My husband changed jobs, and now we are here for an indefinite period, planning to stay until our children finish school.

Where did the idea of a Hungarian weekend school come from?

When we returned to Tokyo in 2019, our children were already in fifth and sixth grade, so I wanted to work. However, it isn’t easy to find proper intellectual work here. We talked with the Hungarian ambassador about work possibilities, and it came up that there were more and more Hungarian children in Tokyo, so perhaps I could try founding a Hungarian weekend school—there might be interest. First, I researched how such weekend schools operate in other countries, contacted school principals, and had long conversations with one in England and another in the U.S. Then, I announced launching it, thinking that if 10–15 children signed up, it’d be worth starting. Far more than that applied—around 25–30 children of various ages, from the youngest to 18-year-olds.

In December 2019, the Liszt Institute opened in Japan, and the ambassador asked that the school be located there as well, so I didn’t look for another venue. Even though the Covid pandemic hit, I launched the school in March 2020. Everyone brought masks and their own supplies, I disinfected everything, and we even took temperatures…

We had space for two groups, so we ended up with a baby group and a kindergarten group, which we could run in parallel. Of course, it wasn’t as simple as it sounds now. For example, the teacher who first agreed to join backed out. I was in trouble, but I hoped something would come up. I put on a puppet show just to attract more interest. That’s when one mother among the audience said she was a special education teacher and had time. We quickly became friends and started working together. She took the baby group, and I worked with the older children. I’m convinced that if we come up with good ideas, with God’s help, they will eventually be realized.

Before we go on, tell us about Hungarians living in Japan.

For the reasons already mentioned, the Hungarian diaspora here is very young and small. Only a few hundred Hungarians live here permanently or with residence permits. Most live in Tokyo. There are also several around Osaka, Nagoya, and in Kyoto—although the latter is practically part of the Osaka area. Beyond that, there are a few scattered elsewhere. Apart from us, almost all families are linguistically mixed; in about half of the families, the mother is Hungarian, in the other half, it’s the father. The other parent isn’t necessarily Japanese, but could be American, English, German, etc. In any case, learning Hungarian is not easy for these children. At the same time, the parents are highly educated—perhaps only one or two have not completed university—and for those whose children attend school, the Hungarian language is important.

‘I’m convinced that if we come up with good ideas, with God’s help, they will eventually be realized’

Who attends the school—only children of diplomats? What ages and language levels are they?

They are generally not diplomat children; in fact, I had only one. Most children of Hungarian origin living here are young, at most around ten years old. The oldest was perhaps seven or eight when we started the school. Older children also applied, but only one or two; I couldn’t really integrate them into groups. I met the 18-year-old boy once or twice and spoke Hungarian with him, but then he went off to university.

The Japanese school system is six+three+three years, and students in so-called junior high school already attend afternoon schools almost every day, including weekends, sometimes even until 9 or 10pm. There are such after-school classes in all subjects—students go for what they want to study further, or where they are lagging behind. On top of that come various sports, with weekend games—older children no longer have time for their second or third language. The same is true among other Asian peoples, such as the Chinese and Koreans.

Their language proficiency is thus very mixed and depends greatly on how much the only Hungarian parent speaks to the child at home and how seriously they take bi- or multilingualism. Where they take it seriously, children can speak Hungarian at a conversational level, both younger and older ones, which is fantastic, considering we only meet every two weeks for an hour and a half. Even so, after a few sessions, their skills improve to such a level that children who previously didn’t speak at all begin to do so. Young children are especially receptive; I often reassure worried parents that after a couple of sessions, their child will know how to express themselves, however imperfectly, in Hungarian.

Parents who don’t take it seriously—there were quite a few at the beginning— expect miracles from us while not speaking Hungarian with their child at home. No matter how much I explained that it’s wonderful that their child comes here, has a community, and practices this ‘strange’ language that only mom or dad speaks, what’s the point of learning it if they never use it at home? Those who didn’t take it seriously, or had other priorities, gradually dropped out. Some moved away—there are many expat managers here who rotate every two or three years.

What is the situation now, five years later?

As we speak, about 35 children attend. Around 10–20 per cent are usually absent due to sports or illness, but 20–25 per cent are always present. There is no longer a separate baby group but a combined baby–kindergarten group, and two school-age groups. Many children who came from the very beginning still attend, but there are always some dropouts and newcomers as well. Over the past five years, about 60 children have passed through my hands.

We operated at the Liszt Institute for four years, then had to leave because the new management no longer supported having the school there—Saturday counted as overtime for them. Meanwhile, Zsuzsi, who partnered with me and worked with the youngest children, had to move back to Hungary—she too was an expat manager’s wife; we said goodbye with tears in our eyes two years ago and have stayed in touch since. I had to redesign everything again. It’s very difficult to find an affordable and good venue here. Municipal spaces are allocated by lottery, but only one month in advance, so you cannot plan with them, while other places are very expensive.

The place I eventually found has only one room, so since then I have taught all three groups one after the other, staggered. From 10:00 to 11:30, the youngest are there; at 11:00, the older ones arrive, and in the last half hour, we do crafts together.

For a year and a half, a wonderful, creative artist helped us make things the children could take home. At 11:30, come the children learning to read and write, and finally, those practicing reading comprehension; we always do crafts with them as well. I found a very good book for them with simple, clear texts.

Choosing teaching material is difficult: there is no point in teaching words like, for instance, suba (a traditional sheepskin coat), because although it’s a beautiful word, they will never use it. It’s fine if they encounter it, but it’s not essential that they know how many kinds of coats people wore in the old days… I also teach cursive writing, which I think is useful. Since children here write kanji, they already have a sense of how to form letters beautifully. We have moved several times since then, and I’m again looking for a new place. But it’s not a problem—so far, the families have always followed me, and fortunately, no one has dropped out because of this.

Do you also mark national and church holidays?

We celebrate Mikulás (St. Nicholas’) Day, Christmas, Easter, Carnival, and Mother’s Day; on those occasions, I dedicate the school session to the theme. When we were still on good terms with the ambassador, we also organized Mikulás and Carnival celebrations at the embassy. Now, national holidays and Mikulás Day are organized by the Liszt Institute or the embassy, but somewhat differently than I’d do it. Once a year, there is a picnic hosted by the Liszt Institute, which was started by the local Hungarian community many years ago. I mentioned to the Liszt Institute that we’d be happy to present a small program on our national holidays, but their response was that the capacity of the venue is limited, and more people apply than can fit.

You also organize school camps. Tell us about those.

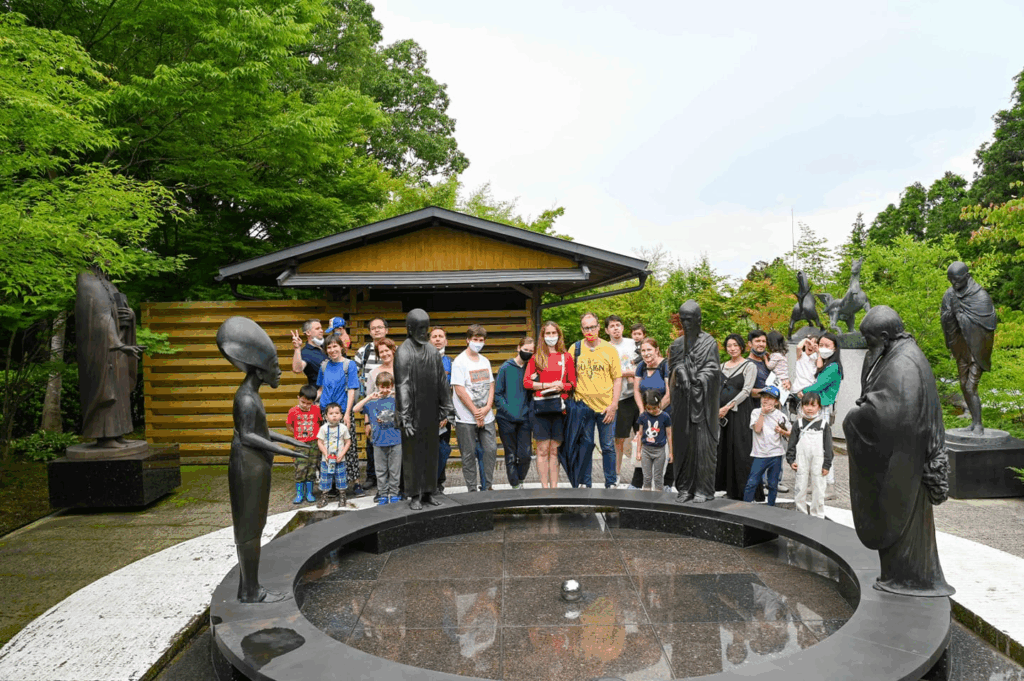

Every year, I organize a one- or two-night family camp, which really brings school families together. This year we had the fourth of these; usually 30–40 people attend. We have been to several places, always in nature, and now I have found a perfect location that we will return to. Several Hungarian artists live in rural Japan. First, we went to ceramic artist Tímea Lantos. Later, she moved and bought a small house with her own workshop in the same town; next time we went there. In the third camp, there was no Hungarian artist nearby, but we still had a great time. Most recently, we stayed close to Sándor Zelenák, a versatile artist who leads creative activities in kindergartens and schools.

In the camps, we try to cook Hungarian food, for example, goulash. But bográcsozás (cauldron cooking) isn’t simple here; there are no big vessels. I managed to obtain an unused cauldron from the embassy that a friend had brought long ago and that I found in the basement, and which I borrowed. We cooked paprikás krumpli, we grilled, made sausages, liver pâté, körözött, lángos, fánk, palacsinta, and even pretzels once. Whatever works, we try—we always aim for something Hungarian and healthy. There is a mother from Transylvania who bakes excellent yeasted pastries; she usually makes sourdough bread for us. I’m very grateful to her! She also helps me with school-related paperwork.

Are there other Hungarian events or communities in Tokyo?

The Liszt Institute organizes a Hungarian festival every year, with the usual market stalls, Hungarian products and food items—including kürtőskalács (chimney cake), lángos, goulash—and folk dance performances. Once, our school also put on a short ten-minute stage program, dancing and reciting poems. There is a folk dance group called Odoribe, made up of non-Hungarians who learn and perform Hungarian dances; they are lovely, trained by the Csillagszemű ensemble from Hungary.

The founders of the latter, the Tímár family, also visit them and us from time to time. Unfortunately, Hungarians don’t regularly attend that group, but when there is a larger event—such as a dance hall occasion once or twice a year—we usually visit them with the school. I wouldn’t say interest is huge; the last time about five children came. The truth is that the Covid pandemic disrupted everything here as well. For two years afterwards, almost no events were organized, and even later, community life restarted very slowly…

As for churches, people here don’t really go to church. There are no retreats either. The Japanese are Shinto and/or Buddhist; very few are Christian. There are Christian churches, but I know only one family that attends service regularly. We are also too small for scouting; we couldn’t sustain it. I’d like to start a scouting-like hiking group, but so far it hasn’t worked out. There is a woman who returned here from Berlin—her husband is Japanese; her son is the aforementioned 18-year-old now at university—and we talked about this; she told me about Hungarian scouting in Berlin. I support the idea very much, but since neither of us is a scout and there are no others either, the brainstorming has stalled for now. However, I do organize picnics: twice a year, we meet in a large park with families—open to everyone, not just schoolchildren. It’s an informal, potluck gathering in nice weather, during cherry blossom season; we speak Hungarian, enjoy ourselves, and everyone brings something Hungarian.

In addition, there is a Hungarian club on the first Saturday of every month. I didn’t start it, but when we returned to Japan, I became more involved, and now there are many more of us than before. My friend Gáspár Sinai came to Japan in the late 90s; he is the soul of it. Several people started back then, but he is the only one who still lives here. We met in a restaurant for a long time; now it’s another public venue. There were times when two or three, nowadays up to 20, gather and talk for three hours. It’s a good group, with people of many interests. We could certainly organize lectures or discussions about, e.g., poems or books, but for that we would need a separate room of our own. My great dream is to have a Hungarian House—with the Hungarian school, the Hungarian club, a library, cooking courses, lectures, Hungarian decorative objects, pictures, etc.

Is there a Hungarian community life outside the capital?

Not that I am aware of. I’m the only one who founded a weekend school, which I also launched online; a few people applied that way. These weekday virtual lessons—essentially private classes—were created for those who, because of geographic distance, cannot attend in person but want to learn Hungarian. However, the dropout rate is quite high there. I planned to have group lessons, but I didn’t have enough children to form groups. There were three boys of the same age group, but now there are none. Currently, I teach two girls online; we’ve been doing this for four years, once a week for an hour. The younger one was only four when we started, and now she reads and writes in Hungarian.

In the U.S., this is typically voluntary work. How does it work in Japan?

I believe parents only take it seriously if they pay something for it. Of course, I don’t ask for much; I try to keep the school affordable. There are no post-war or 1956 political refugees here; it’s a completely different environment. Hungarians living here are typically economic migrants, and I provide a service for them that involves a lot of work.

You’ve mentioned that the Japanese are a less welcoming nation. In what other ways are they different from Hungarians, and how does this affect people, for example, Hungarian children living in Japan?

The Japanese are very different from Hungarians; their way of relating to one another is very different from ours. For example, they are much more patient and slower-paced. Japan is predictable and calm; people are far more balanced. For example, in everyday life, they don’t really deal with politics. They vote, but it doesn’t affect them deeply, and politics does not creep into daily life, family life, or work at all. I think this is a huge difference, especially now.

Children bully each other less. Of course, there is bullying here too, but much less. In schools, it’s strikingly not a topic of how much money or what clothes they wear. In public schools, there are uniforms, but even in the international school my children attend—together with other diplomat children, including some from extremely wealthy families—there is no such distinction, which is clearly a positive influence of the Japanese environment.

Until sixth grade, children aren’t allowed to bring phones to school at all. Even after that age, they may not necessarily have smartphones, and even in higher grades, they must turn them off and cannot use them during breaks. My children at the international school work entirely on laptops; they have no textbooks or notebooks at all, but they, too, may not use their phones at school.

When we moved here, they were in fifth and sixth grade and already had phones. We allowed them to keep them here, so they could call us if it was necessary, but they said it wasn’t allowed, and it wasn’t necessary anyway, because we live close to the school. Here, children attend their local district school based on residence; a very serious reason is needed to deviate from this, such as a parent’s workplace. This applies to the first six grades; afterward, they go to schools based on entrance exams. I think this rule is excellent: everyone lives nearby, there is no congestion, and children walk to school independently from first grade.

Is Japan safe enough for this today? Are parents home by then?

Of course, anything can happen anywhere, but incidents are very rare. There is a school guard system: retired people volunteer to stand at intersections in the mornings and afternoons, wearing visible vests and guiding children with small batons. At school, all classes are dismissed at the same time; children wait for one another at the gate and, after saying goodbye, walk home in groups. They do not wander alone; they follow a predetermined route and are not allowed to deviate from it. This is also important for safety during frequent earthquakes.

Parents are home by then; many mothers don’t work or only work part-time. With this system, children are raised not only to be more independent but also to look out for one another. In schools and workplaces, the focus is always on groups/teams: what is my situation in my group, what I can contribute to the success of my team.

The Japanese are very group-oriented, and I see this in the Hungarian children here as well: they are easy to work with in teams, calmer, with fewer restless children. It may or may not be connected to limited phone use, but fundamentally, the Japanese are much slower-paced. And although children don’t use smartphones much, there are many other safety solutions—for example, simple two-button phones for young children (to reach out for mom and dad), or emergency alarm buttons on school bags that emit a very loud sound when pressed. This is that kind of society: they think ahead and prepare; they don’t wait for trouble to happen.

Related articles: