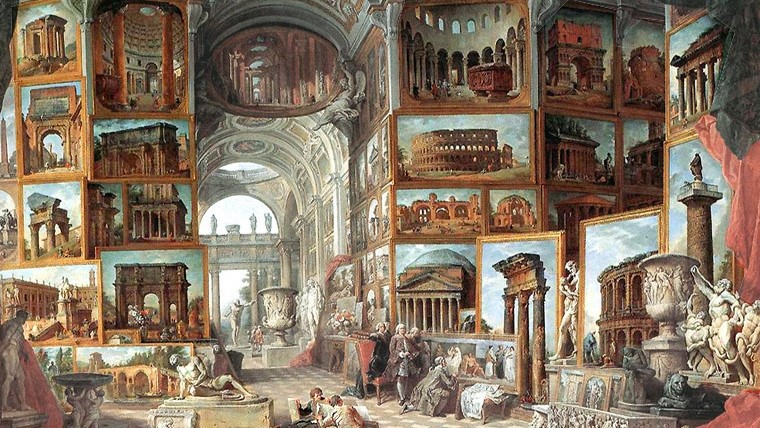

I’ve always wanted to die in Rome. As a historian working on foreign policy realism, few locales evoke a deeper sense of civilizational continuity than Rome, Constantinople (Istanbul), Beijing, Alexandria, and Delhi—cities whose institutional and cultural lineages extend uninterrupted across millennia.

Rome in particular is different, and occupies a privileged position, especially if you’re based in Washington, DC, the New Rome and the beating heart of the mightiest empire of our times. This affinity is accentuated in the United States, where the appellation ‘New Rome’ is frequently invoked, avoiding intermediary claimants such as the Byzantine or Holy Roman traditions.

Europeans occasionally refer to the United States as the‘Fourth Rome’, yet within American discourse, the designation is simply the ‘New Rome’, implying direct succession to the Urbs Aeterna.

This self-conception is not simply rhetorical; the American founding fathers consistently evoked Rome to create a new republican order amid the imperial monarchies of the 18th century. James Madison had to translate Cicero in his college entrance: Madison’s ‘accumulation of all powers…in the same hands…may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny’ is as Ciceronian as they come. ‘Among the numerous advantages promised by a well-constructed union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction,’ Madison wrote, about majoritarian mobs, echoing Cicero’s warnings against Ochlocracy.

The United States is, of course, chronologically young, but still constitutes the oldest continuously functioning republican democracy in the modern era. Its constitutional architecture, separation of powers, and federalism bear the imprint of Roman models, particularly as articulated in Madison’s Federalist contributions, which grapple with the dangers of concentrated authority. The perennial question, however, remains: which Rome does contemporary America most resemble, the Republic or the Empire? This question is important, especially in an era of emergent multipolarity, domestic polarisation and strategic overextension.

‘The United States is…young, but still constitutes the oldest continuously functioning republican democracy in the modern era’

Notwithstanding profound transformations, the United States retains the formal attributes of a republic: periodic elections, an independent legislature, and the conspicuous absence of military praetorianism. Even during existential crises such as the Civil War, the Great Depression, the world wars, or the post-2001 security state, power has ultimately reverted to civilian institutions. Violence has been periodic, but violence is also not inherently antithetical to republican governance; the American experience from frontier expansion and the Civil War to 20th-century total wars demonstrates that republics can sustain high levels of organized coercion without necessarily undergoing a caesarian transformation.

On the other hand, accusations of incipient dictatorship accompanied nearly every consequential presidency, from Abraham Lincoln to Teddy Roosevelt, Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan, Barack Obama to Donald Trump, and yet the institutional framework has managed to endure. History, of course, seldom repeats itself, but structural parallels persist. Every durable empire has confronted the challenge of integrating diverse populations while preserving a cohesive imperial ideology. Successful polities, such as Rome, the Ottomans, the British, and the Habsburgs, achieved this equilibrium until the point where majoritarianism and ochlocracy destroyed the imperial core.

The United States enters this new multipolar era suddenly deficient in any assimilative narrative. The US isn’t a classical empire with hierarchy and a narrow imperial elite, nor is it a classical republic with racial homogeneity and an entrenched senatorial class opposed to any mob dynamics. The Romans and the British transcended ethnicity: one could be a Roman from Syria to England, just like one could be a subject of the British Empire, from Canberra to Calcutta to the Caribbean.

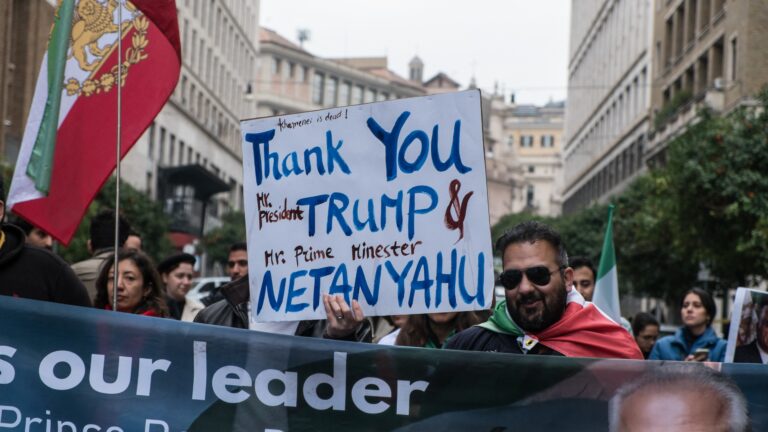

Contemporary American identity, however, lacks a comparable universality, while taking the character of an empire inviting meritocratic newcomers to join the manpower pool required for hegemony. But the newcomers are imperial subjects in some form and reflect an imperial cosmopolitanism, thereby pushing a dormant nativism. The 2024 electoral coalition that returned Donald Trump to office, encompassing significant Hispanic and Asian working-class constituencies, illustrates the potential for a multiracial civic coalition.

But creating such a coalition is an easy task. Sustaining such a coalition, however, demands persuasion towards a universal narrative, rather than an imposition of norms; policies perceived as punitive (immigration raids on legal immigrants, indiscriminate tariffs, protracted peripheral conflicts) risk alienating recent adherents and undermining long-term cohesion. Any policy prescriptions must therefore prioritize efficiency over such performative severity.

‘The 2024 electoral coalition that returned Donald Trump to office…illustrates the potential for a multiracial civic coalition’

Take the example of illegal immigration, which could be more effectively curtailed through simpler employer sanctions and steep remittance taxes than through televised operations that engender humanitarian backlash, and childish and provocative social media posts. Likewise, trade rebalancing would require focused pressure on primary adversaries (China) rather than Hobbesian confrontation with Canada, Mexico, India, Japan, South Korea and the EU simultaneously.

Additionally, foreign policy retrenchment would require a total disengagement from intractable commitments in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, rather than a never-ending mediation.

The lesson from Rome’s fate was not the result of agency, but also of structure: great power rivalry with Parthians in the East, unassimilated Germans within. Similarly, the United States now confronts similar structural challenges of finite resources, dwindling manpower, and peer adversaries, as well as multiple unassimilated tribes within, absent a single unifying frame of narrative.

Prioritization is not just necessary but inevitable. A prudent imperial strategy would entail a partial retrenchment in theatres which are not existential to the US security or prosperity. History is littered with great powers prudently retrenching without shrinking or collapsing. Rome itself survived the fall of its western provinces by shifting its focus to the richer East; Britain gave up its North American colonies, yet went on to build a larger empire in Asia.

Today’s American strategic readjustment is a similar recalibration, not a cliched retreat into isolationism. In a multipolar world, the United States will have no option but to negotiate openly with other major powers about each side’s core interests, much as Washington and Moscow tacitly divided spheres of influence during the later Cold War.

‘Successive generations of American adults, including every serving military officer, have no personal memory of the horrible costs of a great-power war. Few people recognize that, prior to this exceptional era of peace, a war in each generation or two was the norm,’ wrote Graham Allison in Foreign Affairs, adding that ‘most concerning, the tendency of an established power to descend into bitter political divisions at home paralyses its ability to act coherently on the world stage. This is particularly troublesome when leaders oscillate between opposing positions on whether and how the country should maintain a successful global order. This is unfolding today: an ostensibly well-meaning administration in Washington is upending nearly every existing international relationship, institution, and process to impose its view of how the international order must change.’

Perhaps it is time to return to Rome’s lessons, just as the founding fathers intended. One such core lesson would be to return to Cicero’s careful distinction between raw popular power (potestas in populo) and the guiding authority of a seasoned elite (auctoritas in senatu). Respect for a competent, meritocratic elite has faded fast, partially due to the existence of an incompetent elite, but also undermined by the endless democratization of information and the cultural pressure to treat all opinions and backgrounds as equal. Rome’s example still matters. If the United States wants to thrive in a renewed age of imperialism, it will need a fresh, inclusive national creed that can rise above tribal and ethnic loyalties yet still enforce clear limits on what the country tries to do abroad.

Related articles: