In early 1990, when the Soviet Union retreated from Central Europe and the democratic transition away from socialism started, everybody was an optimist.

The plan was that Hungary would dismantle Communism, chase out the Soviets and then everything would be fine. The market economy would come, liberty would flower, and society would arrive at a golden age.

Of course, this did not happen. Just after the democratic government was formed and the political season started in the autumn of 1990, a crisis hit.

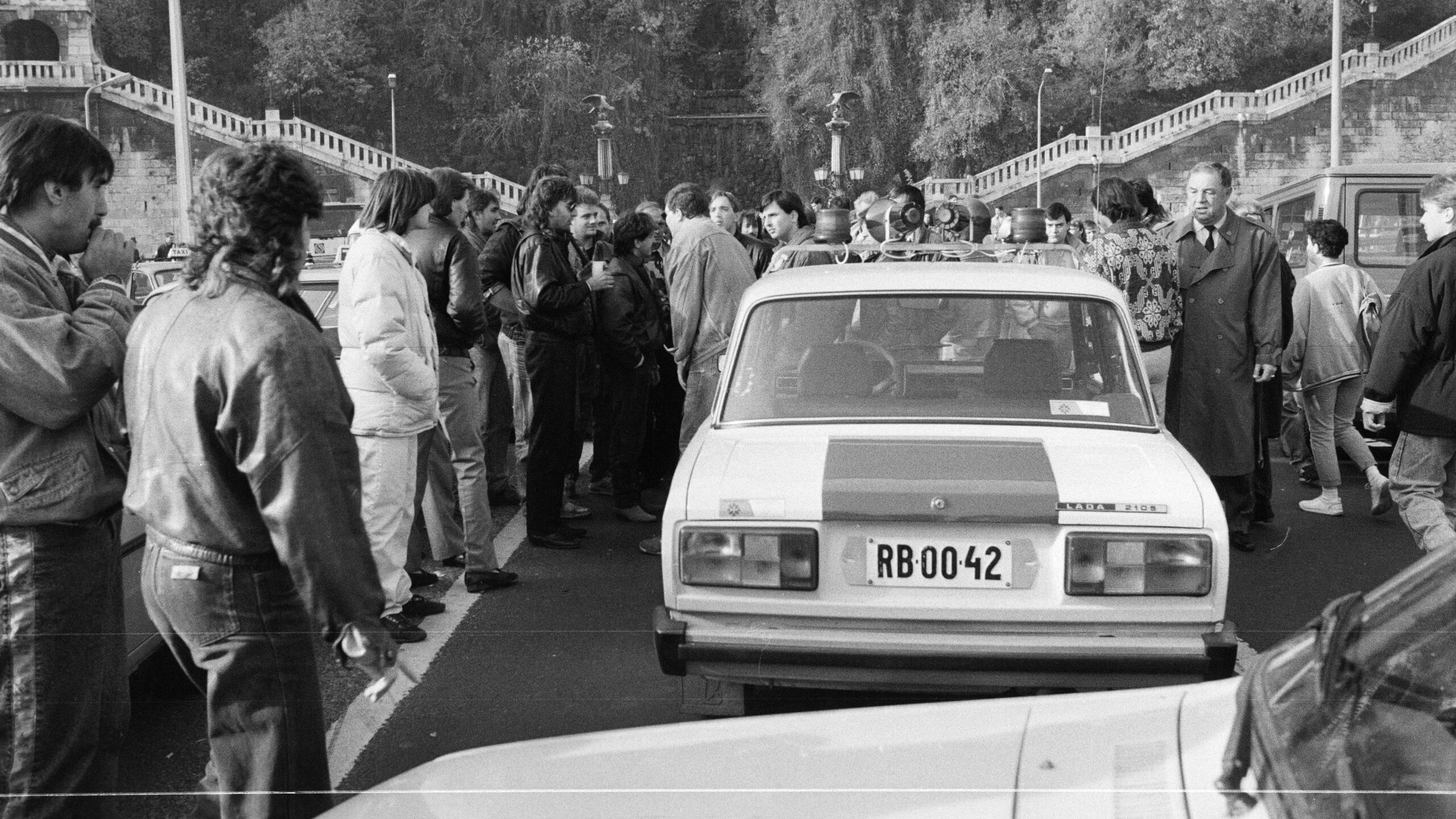

On 25 October, transport workers began to blockade major national roads, as well as the central arteries of Budapest.

Their demand? The reversal of sudden fuel price hikes by the government.

The battle lines were clear and the conflict a classic one. Hungary needed to dismantle Communism in the sense of throwing away the artificial fuel price system that deformed the economy and overburdened the national budget. The transport workers, facing this reality, however, tried to bully the government into submission through the total arrest of the transportation of the nation.

The economic liberalization lagged, and it eventually cost the centre-right the election in 1994.

Debates are still raging on the first major crisis of Democratic Hungary. Most of these are concentrated around the role and plans of national political forces. For example, did the government want to deploy the military to clear the protesters? As it is correctly portrayed in the 2023 film Blockade, the quickly abandoned plan was for military engineers to remove vehicles, and, as Ernő Raffay, then Undersecretary of Defence claimed, to deploy and keep open a temporary bridge from the north of Budapest.

Other debates are about the role of the sitting President, Árpád Göncz, who was supported by the liberal SZDSZ. Göncz blocked the use of military vehicles by the army against the protesters’ cars, invoking his position as Commander-in-Chief, which was then deemed unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court.

Pro-government protesters during the blockade claimed that it was actually an ongoing coup by the liberal SZDSZ. The use of the crisis by the liberal groups for political goals is still a sore issue for many on the centre-right and one of the, although already fading, origin points of the still-ongoing feud between political groups.

However, there is a dimension that remains understudied but, in light of the crisis’s severity, offers valuable insight into how profoundly international events can affect small states—often without those states fully grasping the underlying causes.

The element in question is, of course, oil.

Hungary by the 1970s was totally embedded in the Soviet energy supply system. The Communist superpower would supply relatively cheap fuel to its vassals, which quite literally chained them to the bloc’s extractive industries, giving the overlords of the Kremlin a key to control them.

Then, glasnost arrived. The Russians urged reform so rapidly that the orthodox Communist countries, like the GDR of Honecker and Romania of Ceaușescu started to drift into anti-Russian rhetoric because they were not ready to embrace democratic reforms now pushed by the Communist centre.

On 25 October, 1989, it was made clear by Mikhail Gorbachev that the Brezhnev Doctrine would not apply any more, which threw the Orthodox Communist parties in front of the proverbial wolves. The rest was history.

The material realities of Soviet oppression, however, remained. One was the vast military presence stationed across the vassal states; the other was the question of energy supply. The key dilemma was how this system could function in a new and untested order—one where the Soviet Union still existed, but the countries on the other end of the pipeline had become democratic.

It was a paradoxical situation, and the small states were playing with a bear that was still capable of erasing them with a stroke of its paws. In June 1990, József Antall proposed the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact, while the Kremlin still held the key to the energy supply of Hungary.

In late 1990, as Eastern Europe democratized, there was already a fear of orthodox communist backlash in Moscow. By the end of 1990, it was slowly materializing. Moscow started to tighten the leash on the Baltic countries that were slowly edging towards independence, while in the already independent Eastern Europe, it slowly choked the Russian oil supply. The decrease was to be tackled through the decrease of consumption, and a state method was to increase prices

‘Hungary found itself caught between the shifting forces of a transitional moment in history’

The situation was only made worse by the dire state of the international economy. On 2 August, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, resulting in a wholesale oil embargo being imposed against Iraq. The global supply was not choked off in a quantitative sense, but the easily processable, light Iraqi and Kuwaiti oil disappeared.

Hungary found itself caught between the shifting forces of a transitional moment in history. On one hand, Moscow sought to cling to its waning power while preparing financially for a post-imperial future. On the other, the United States, newly unrestrained in its global role, focused on regulating a ‘rogue state’ on the periphery.

Why couldn’t it cope better? The US and France introduced measures to curb retail price increases. But it was one thing for major economic powers to issue ultimatums to market players, and quite another for small, open economies that depended on the goodwill of global market forces during their transition. Ultimatums would have cut off supply, while price subsidies were financially unsustainable.

In the end, the cabbies were offered a 12 forint/litre compensation to alleviate petrol costs. The government was forced to muddle along with overspending, which, in the end, led directly to the ‘bitter pill’ of the 1995 economic reform package of Lajos Bokros and the new Socialist-Liberal government, resulting in massive state spending cuts.

Democratic Hungary was born in the middle of an energy crisis. It is no surprise that securing a steady and affordable supply of natural gas, petrol, and electricity is an imperative at all times. Choking off the lifeline of a modern society is a deeply embedded anxiety of Budapest: for present and future allies of Hungary, it is imperative to offer the country a deal where energy is accessible and affordable.

Related articles: