When Margaret Thatcher declared that ‘the root of freedom is moral responsibility,’ she was not making a merely political statement. She was restating, in modern terms, a theology that stretched from the Dutch theologian Jacobus Arminius through the Methodist revival of John and Charles Wesley, to the civic-minded sermons of her own father, Alfred Roberts. Thatcher’s small-L liberalism—the belief that individuals, not the state, bear moral responsibility—was not imported from Chicago economics or Hayekian rationalism. It was the natural outgrowth of her Arminian Methodist faith.

The Theological Roots of Liberalism

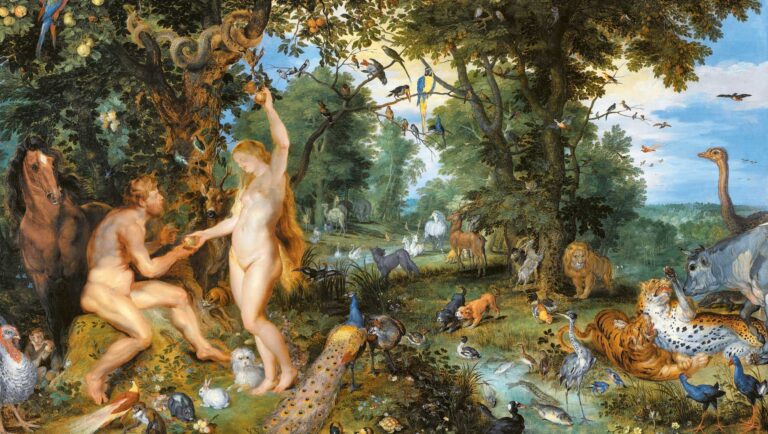

Arminianism, the branch of Protestant theology embraced by the Wesleys, rejected the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. For the Arminian, God endowed man with liberum arbitrium, free will, so that human beings could freely accept or reject divine grace. Salvation was not mechanically imposed; it required personal responsibility. God’s grace was prevenient—it came first—but it did not coerce. This vision of human freedom as both given and obliged was the moral seed of Thatcher’s politics.

Methodism was thus a religion of moral agency. Its hymns and sermons emphasized self-discipline, stewardship, and thrift not as bourgeois virtues but as forms of spiritual training. Charles Wesley’s journal was pointedly titled The Arminian. To be Methodist was to believe that God made men free so that they could learn responsibility. The poor were not to be pitied as victims of fate, but assisted in cultivating their own dignity. In that sense, early Methodism was profoundly non-paternalistic.

From Theology to Law: Grotius and the Natural Liberty Tradition

The Arminian view of freedom did not remain confined to theology. In the early 17th century, Hugo Grotius—Arminius’s contemporary and sometime ally—translated this anthropology into a new jurisprudence. In De jure belli ac pacis (1625), Grotius argued that God ‘created man free’ (‘liberi’), and that this natural liberty was not erased by sin or social convention. Wherever men were capable of making and keeping promises, law could exist. This principle became the cornerstone of modern natural law and, eventually, of liberal politics.

Grotius’s conception of ‘perpetual natural liberty’ shaped the moral foundations of contract, property, and exchange. It is no accident that his other famous treatise, Mare Liberum (The Free Sea), laid the groundwork for free trade. Half a century later, Scotland’s greatest jurist, Lord Stair (James Dalrymple), began his Institutions of the Laws of Scotland with ‘Freedom’ as its first article, explicitly drawing on Grotius. By the time of Adam Smith, this Arminian-Grotius line of thought had matured into what Smith called ‘the simple system of natural liberty’.

Thus, the liberalism of the Scottish Enlightenment—often caricatured as secular or utilitarian—was in fact the legal and moral outworking of a Christian anthropology: man as a free, responsible agent under God.

The Methodist Middle Class and the Politics of Agency

By the 19th century, Methodism had become the religion of Britain’s industrious middle classes—shopkeepers, tradesmen, and small farmers—who lived out their theology in daily life. They believed, as Thatcher’s father did, that ‘you cannot build character and courage by taking away man’s initiative and independence.’ One earned communion not by birthright but by conduct; in Methodist chapels, one received a ticket to take the Lord’s Supper only after demonstrating moral readiness. In this discipline of liberty, divine grace was never divorced from personal duty.

‘Human freedom is meaningful only when exercised within moral order’

The Methodist ethos was thus the nursery of liberal self-government. It taught that human freedom is meaningful only when exercised within moral order. The result was a kind of proto-Burkean liberalism: a belief in ordered liberty, rooted in Christian virtue rather than abstract rights. Edmund Burke himself recognized this inheritance, as did Gladstone a century later. Freedom without formation was license; formation without freedom was tyranny.

Thatcher’s Inheritance

Margaret Hilda Roberts grew up in this world. Her father, Alfred Roberts, was a grocer and lay Methodist preacher in Grantham. The rhythms of Scripture and the cadences of Wesleyan hymns filled her youth. Her faith was earnest, practical, and unsentimental. In her ‘Sermon on the Mound’ (Church of Scotland General Assembly, 1988), she would later summarize it thus:

‘The truths of the Judaic–Christian tradition are infinitely precious, not only because they are true, but because they provide the moral impulse which alone can lead to that peace, in the true meaning of the word, for which we all long.’

Here, as throughout her life, Thatcher’s appeal to liberty was inseparable from the idea of moral formation. Freedom was not a natural condition to be indulged, but a divine vocation to be cultivated. As she said in her 1976 speech to the Conservative Party Conference: ‘The root of freedom is moral responsibility.’

To the dismay of her critics, this was not the language of laissez-faire individualism. It was the language of Wesleyan moral theology.

Against Determinism: Faith and Politics Alike

Thatcher’s liberalism was therefore anti-determinist in both its theology and its economics. Just as she rejected the Calvinist idea of predestination in religion, so she rejected socialist determinism in politics. Both systems, in her view, denied the reality of moral agency. Calvinism placed the soul’s destiny beyond human choice; socialism placed human prosperity beyond human effort. In both cases, the person was diminished.

‘The root of freedom is moral responsibility’

Her conviction politics—her refusal to yield principle to popularity—rested on the Arminian premise that the moral agent must act in accordance with conscience, not convenience. ‘Of course it is the same with individuals,’ she told Woman’s Own in 1987. ‘We are all responsible for our own actions. No one else can answer for us before God.’

This, not market ideology, was the heart of Thatcherism: the insistence that liberty and duty are inseparable, and that social flourishing begins with individual moral renewal.

Liberalism All of a Piece

For this reason, Thatcher’s politics were ‘all of a piece’. The same conviction that animated her faith animated her economics. She was not, as her detractors claimed, an ideologue of greed or a cold apostle of the market. She was a Christian liberal of the old school, convinced that government should not do for people what they could—and must—do for themselves.

Her emphasis on thrift and enterprise was moral, not merely material. It was the application of Arminian anthropology to modern society. As she once said: ‘Economics are the method; the object is to change the soul.’

This spiritual liberalism also explains her implacable opposition to communism. She saw in Marxist atheism the same denial of freedom that Arminius saw in Calvinist predestination. In both, the will was bound—whether by fate or by the state. To liberate man was to restore him to his moral standing before God.

The Christian Coalition of Liberty

In this, Thatcher stood in a triad with Ronald Reagan and John Paul II, each drawing on a shared Christian anthropology of freedom. Reagan’s ‘Evil Empire’ speech (1983) and John Paul’s call to ‘Be not afraid’ (1978) articulated the same conviction: that liberty is not the gift of the state but the endowment of the Creator, and that it must be exercised in righteousness.

Together they opposed not only communism’s political tyranny but its theological falsehood—the denial that man is a responsible moral creature. The collapse of Soviet atheism, as much as of Soviet economics, was the vindication of their belief that freedom requires a soul.

The Liberalism Worth Keeping

In our own ‘post-liberal’ moment, Thatcher’s Arminian liberalism deserves a second look. Liberalism, rightly understood, was never meant to be the cult of the autonomous self. It was the civic translation of a theological truth: that we are created free so that we might learn to use freedom well.

Modern liberalism’s sickness lies not in its origin but in its amnesia. It has forgotten that the moral foundations of freedom are spiritual. Thatcher did not. Her Methodism, far from being an ornament of her youth, was the organizing principle of her politics.

‘Liberty is not the absence of restraint but the discipline of responsibility’

She embodied what Burke glimpsed, what Grotius articulated, what Wesley preached—that liberty is not the absence of restraint but the discipline of responsibility. It is the divine apprenticeship of the will.

The Duty of Freedom

Margaret Thatcher’s liberalism was not a departure from Christianity but its political expression. From the Arminians to the Methodists, from Grotius to Burke to Smith, a single thread runs through the centuries: God made man free so that he might be responsible. Thatcher wove that thread into the fabric of British politics.

If we wish to preserve freedom in an age weary of it, we would do well to recover her insight: liberty is not self-generated, but God-given—and it is sustained only where men and women are trained in its duties.

Related articles: