Peter’s accession to the throne in 1038 came as no surprise to anyone, as the decision was made by King Stephen (r. 997/1000–1038), who laid the foundations of the Christian Kingdom of Hungary and was canonized in 1083. Of course, not everyone was happy about it, but seeing the sad fate of Vazul, King Stephen’s cousin and pretender to the throne—he was blinded, had led poured into his ears, and his sons were exiled—his contemporaries did not dare to oppose him.[1] As a foreigner, ascending to the throne with an uncertain power base and supporters always posed a serious threat. After the Árpád Dynasty died out, the Czech pretender, Wenceslaus of the Přemysl Dynasty (King of Hungary 1301–1305), ascended to the throne. He even changed his name to Ladislaus in order to succeed, and made Otto Wittelsbach, Prince of Bavaria (King of Hungary 1305–1307), who had no chance despite his family ties, quickly leave Hungary. An exception was Andrew III (King of Hungary 1290–1301), who, like Peter, also came from Venice and became a successful and good king. He was the posthumous grandson of King Andrew II (d. 1235), whose contemporaries overlooked even his obscure origins.

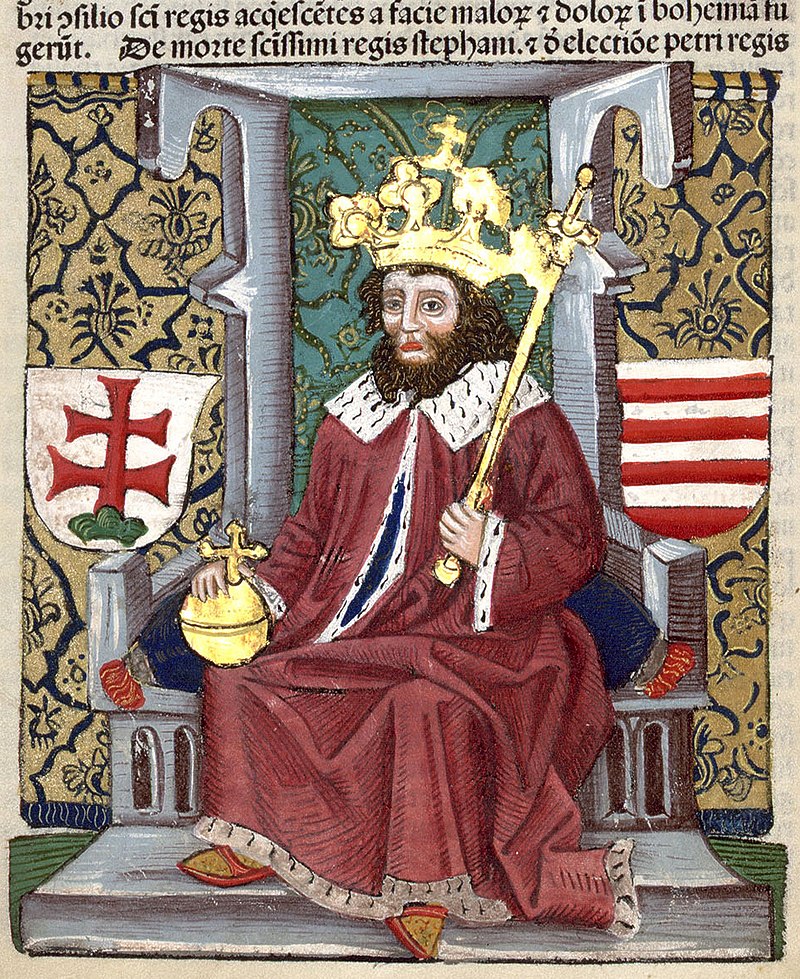

However, Peter Orseolo (r. 1038–41 and 1044–46) was not just anyone; he came from a dynasty that had produced four doges of the richest city state on the Adriatic coast. His ancestor, Pietro I Orseolo, came to power in 976 and had the city’s iconic buildings, St Mark’s Basilica and the Doge’s Palace, renovated.

Despite his successes, two years later, he left the city in the company of Saint Romuald and decided to become a monk and then a hermit, entering the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa (Catalan: Sant Miquel de Cuixà) in Prades (Prada) in southern France. He was already revered as a saint by his contemporaries, and in 1027 he was canonized by the local bishop, which was confirmed by the pope in 1731.

It is little known that among the Hungarian kings, Peter, like the Árpáds, could boast of having a saintly ancestor. His son, Pietro II Orseolo (r. 991–1009), was no less famous as Doge of Venice, defeating the Dalmatian pirates. This is commemorated to this day on 9 May with the Sposalizio del Mare (Marriage of the Sea) festival, representing Venice’s maritime power. In 1001 the German Emperor Otto III personally visited Pietro II and became the godfather of his son, Ottone. Ottone’s wife was the sister of King Stephen I of Hungary, sometimes referred to as Grimelda, and thanks to this dynastic connection, their son later also became King of Hungary.

Ottone (r. 1009–1026) already had a more eventful life. After being driven out of Venice by a rebellion in 1023/24, he found refuge in Constantinople in 1026, as he was also related to the Byzantine emperor. However, his wife and child, Peter, born around 1010, did not follow him but fled to the court of Hungarian King Stephen and remained there.[2]

‘As a foreigner, ascending to the throne with an uncertain power base and supporters always posed a serious threat’

The problems surrounding the succession to the Hungarian throne may have come to a head after the unexpected death of Prince Emeric in 1031. The relationship between the two queen mothers, Emeric’s mother, Queen Gisela and Peter’s mother, had not been smooth before anyway, but after Stephen chose Peter of Venice as successor, it may have reached a low point. By 1038, Peter had already spent 12 years in the country, had been educated at the Hungarian court, obviously knew Hungarian, and had a large number of Hungarian supporters. According to the legend of Stephen: ‘Finally …not doubting that the day of his passing away was approaching, [King Stephen] summoned the bishops and the chief lords of his palace who gloried in the name of Christ, and discussed first with them who was to succeed him as king, namely, Peter, his sister’s son, who was born in Venice and whom he had already summoned to himself and, long ago, appointed leader of his army.’[3]

King Stephen’s move was primarily motivated by foreign policy considerations: in the second half of his reign, from the 1020s onwards, the king pursued a purposeful and independent foreign policy, which may have been necessitated by the death of his brother-in-law, Queen Gisela of Hungary’s brother, Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor in 1024. It was certainly during the last decades of his life that the Orthodox rite nunnery in the Veszprém Valley was founded in close cooperation with the Byzantine emperor, perhaps for the Byzantine princess intended to be the wife of the heir to the throne, Prince Emeric. The founding of the Hungarian pilgrim houses in Jerusalem and Constantinople can also be linked to this period.

The diplomatic conflict preceding the Hungarian German war of 1030 can also be linked to this process: in 1027 the king refused to allow a German embassy, calling themselves pilgrims, to pass through the country on their way to Byzantium. The tense Hungarian–German relations may have justified the selection of the son of the Venetian doge, who was also related to the Byzantine imperial family. Hungarian chronicles record that Peter was hostile towards Stephen’s widow, Gisela, who may have represented the German faction in the country and who soon had to flee.

Until the first domestic political crisis in 1041, Peter remained loyal to Stephen’s legacy, supporting the Czechs and Poles against the German emperor, and sought the support and alliance of Henry III only after his expulsion from the country. With Henry’s help, Peter regained the throne in 1044 and accepted German suzerainty. Not surprisingly, his reign lasted only two years, as in 1046 Vazul’s sons, returning from abroad, overthrew and killed him.

In the 1020s German–Venetian relations were disrupted by the resumption of the centuries-old conflict between the patriarchs of Aquileia and Grado, with the former supported by the German emperors and the latter by Byzantium and Venice. The stakes were high: control over the ecclesiastical influence in Venice. Poppo, the archbishop of Aquileia, with the support of Emperors Conrad II and Henry III, attempted to place Grado, which was ruled by Otto Orseolo, the brother of the Doge, under his own ecclesiastical administration, while attacking it with armed forces. Emperor Conrad did not look kindly on the emerging Venetian–Hungarian alliance, and this may have been the reason behind his attack on Hungary in 1030. It is no coincidence that the archbishop and the emperor can be seen together in a fresco painted during the renovation of the Basilica of Aquileia in 1031.[4]

King Stephen adopted Peter, which was supported by numerous arguments. However, it is possible that Stephen overestimated Hungary’s international influence and the results of domestic Christian conversion. Despite its long and successful reign, the country remained a land of political and ecclesiastical compromises, where a balance had to be struck between the pagan heritage and the new religion, as well as the social forces behind them.

A ruler from Venice, a region with a Christian history dating back several centuries, was ill-suited to this task, and it was no coincidence that his ill-considered actions jeopardized the results of Christian conversion achieved thus far. Peter had already come into conflict with the church leadership during his first reign, when he deposed two bishops. The high priests, including Gerard of Venice, bishop of Csanád, also turned against him, and in 1046 it was in Csanád that the nobles decided to recall Vazul’s sons against Peter.

‘The country remained a land of political and ecclesiastical compromises, where a balance had to be struck between the pagan heritage and the new religion’

The reason for the conflict is explained in the legend of Bishop Gerard and his Latin exegetical treatise Deliberatio. According to this, King Peter introduced imperial practice with the church in Hungary and tried to dispose of its property as his own. The high priests felt it was their responsibility to ensure the survival of Christianity in the country. Still, the people and the church considered the heavier taxation than before to be contrary to this. As Gerard wrote in Deliberatio: ‘Since they are doing such things…the whole army of the lower classes will rise up against us.’

Indeed, the episcopacy rose up against the King in 1041 and 1046, as they were unable to forgive him for breaking with the customary law established by King Stephen regarding churches and religious matters, and for introducing ‘German law’ instead, as it was called at the time. Peter’s downfall in 1046 was linked to a pagan rebellion, which resulted in enormous material and human destruction. Bishop Gerard himself suffered a martyr’s death in what is now Budapest, on the hill named after him, Gellért (Gerard) Hill, and only three of the country’s ten bishops survived.

King Peter did not survive the 1046 rebellion either. He fled with a small group of soldiers towards the western border but was unable to leave the country. As the chronicle puts it: ‘[Peter] took refuge in a mansion and defended himself bravely for three days. At last all his warriors were killed by arrows and he was taken alive; blinded and brought to Székesfehérvár, where in great pain he soon ended his life.’[5]

The King lives on in Hungarian historical memory as one of the ‘worst’ rulers. However, the Hungarian chronicle deliberately blackens his image, describing his reign using the eternal topoi of bad kings and medieval national typology: ‘After Peter had been made king, he cast aside all goodness of royal serenity and raged with Teutonic fury, despising the nobles of Hungary and devoured with insatiable heart casting his proud eyes, together with the Germans, who roared like wild beasts, and the Italians who chattered and twittered like swallows, the wealth of the land. The fortified places, strongholds, and castles he handed over to the custody of the Germans and Italians.’[6]

Contemporary Hungarian public opinion did not consider Peter Orseolo to be a member of the Árpád Dynasty, and his name was not included in the early royal register either. This is not surprising, because from 1046 onwards, it was the sons of Vazul—Andrew (r. 1046–1060) and Béla (r. 1060–1063)—who sat on the Hungarian throne, and historians wrote according to their preferences. Peter’s bad reputation must have been so widespread that even a German source from the end of the 11th century mentions him as an example of a fallen tyrant, the ‘corrupter of his father’s laws’.

‘The King lives on in Hungarian historical memory as one of the “worst” rulers’

Yet Peter was an exemplary Christian. He founded a collegiate chapter and church dedicated to Saint Peter in Buda, similar in size to the one in Székesfehérvár. He also continued the construction of the cathedrals in Vác and Pécs, founded by Stephen. Recent archaeological excavations in the crypt of the cathedral in Pécs, dedicated to St Peter, have revealed what is most likely the tomb of King Peter. The King continued his predecessor’s work in minting coins and legislating, but due to dissatisfaction, none of his laws survived and were not included in the collection of laws of the first kings.

Undoubtedly, the political and ecclesiastical situation in Hungary in the 11th century was not ripe for a politician who was not familiar with Hungarian conditions to ascend the throne. King Stephen did not assess this correctly and thought that the years spent at his court had made his Venetian relative Hungarian. He was mistaken. Without taking Hungarian conditions into account, Peter rashly attempted to transform the country into a Western-style kingdom, and in doing so, he was left to his own devices and failed.

[1] Péter Báling, Az Árpád-ház hatalmi kapcsolatrendszerei. Rokonok, barátok és dinasztikus konfliktusok Kelet-Közép-Európában a 11. században és a 12. század elején, Budapest, 2021, pp. 296–315, 339–359.

[2] Gherardo Ortalli, ‘Petar II. Orseolo – dux Veneticorum et Dalmaticorum’, in Nedo Fiorentin (ed.), Venezia e la Dalmazia anno Mille. Secoli di vicende comuni, Treviso, 2002, pp. 65–76.

[3] ‘Life and Deeds of King St Stephen’, transl. by Cristian Gaşpar, in Gábor Klaniczay, Ildikó Csepregi, and Bence Péterfi (eds.), The Sanctity of the Leaders. Holy Kings, Princes, Bishops and Abbots from Central Europe (11th to 13th Centuries), Budapest, New York, 2023, p. 79.

[4] Herwig Wolfram, Conrad II, 990-1039: Emperor of Three Kingdoms, University Park, PA, 2006, pp. 228–237.

[5] János M Bak, László Veszprémy (ed. and transl.), Chronicle of the Deeds of the Hungarians from the Fourteenth-century Illuminated Codex, Budapest–New York, 2018, p. 163.

[6] János M Bak, László Veszprémy (ed.), Chronicle, pp. 130–133.

Related articles: