The following is an adapted version of an article written by Emese Hulej, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

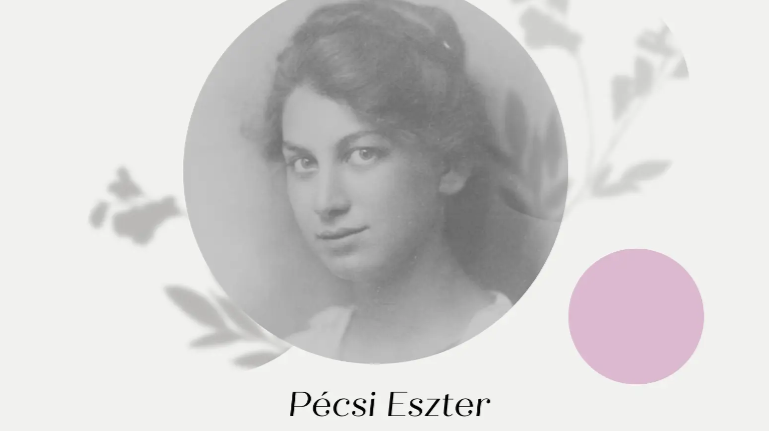

The 20th century through women’s reading: artists, scientists, legendary educators, lifesavers, and society’s favourites. Let us introduce Eszter Pécsi, the first female engineer in Hungary, who prepared the structural plans for the now-famous swimming pool designed by Alfréd Hajós.

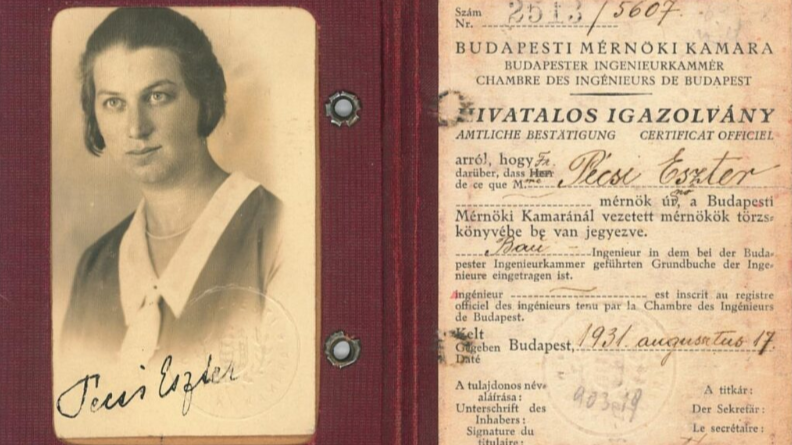

The first female engineer in Hungary received her diploma from the Royal Joseph University of Budapest (today’s Budapest University of Technology and Economics) on 8 March 1920, on her 22nd birthday. When she began her academic studies, Hungarian higher education was not yet coeducational, so she attended the Technical College in Berlin for several years.

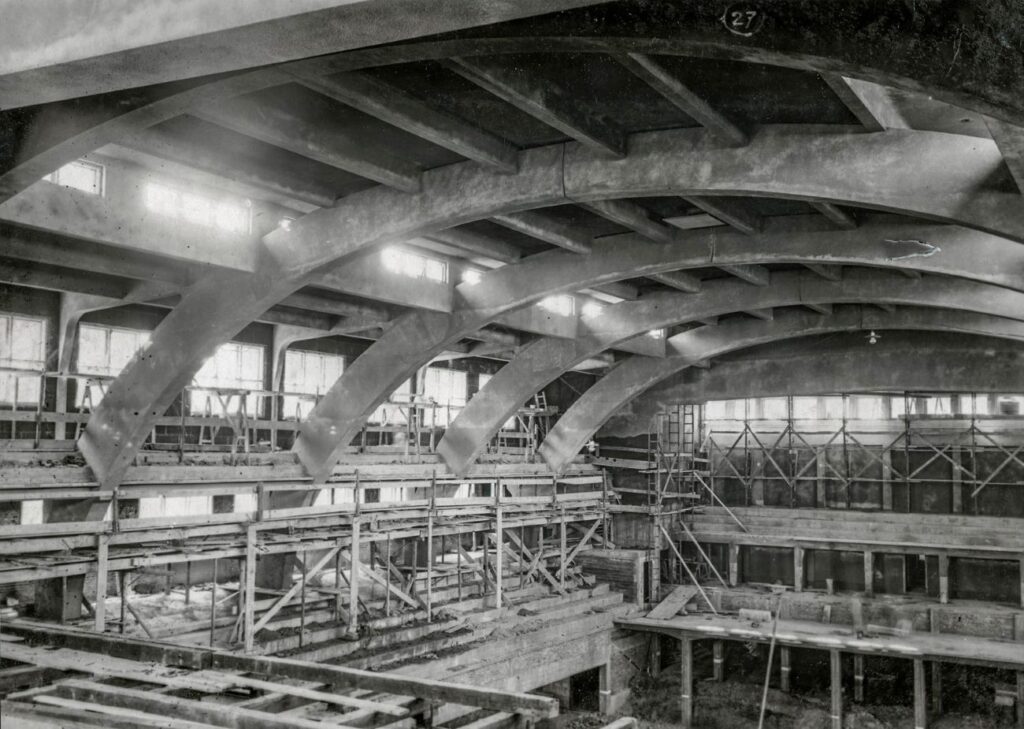

Born in Kecskemét in 1898 as Eszter Pollák, our heroine wanted to become an engineer from an early age and chose the least feminine of all disciplines—structural engineering. She drew up the plans for the reinforced concrete structures of the national swimming pool designed by Alfréd Hajós, and was also responsible for the load-bearing capacity of several major public buildings, including the Kútvölgyi Hospital and the emergency hospital on Fiumei Road.

She worked on foundations, ceilings, and houses with reinforced concrete and metal structures. After World War II, she played a major role in assessing bomb-damaged buildings, and it was her task to reinforce the collapsed roof structure of the damaged National Theatre.

‘[Eszter Pécsi] caused quite a stir, also in the press of the time, with her unusual life path’

After graduating, she got a job at an engineering firm in Budapest, where she met her husband, József Fischer, with whom she set up her own office. Fischer, who had mostly worked as an industrial designer before becoming an architect, designed modern, unconventional buildings, while his wife was the structural engineer. If the story is true, their relationship began when she accidentally spilt ink on his plans.

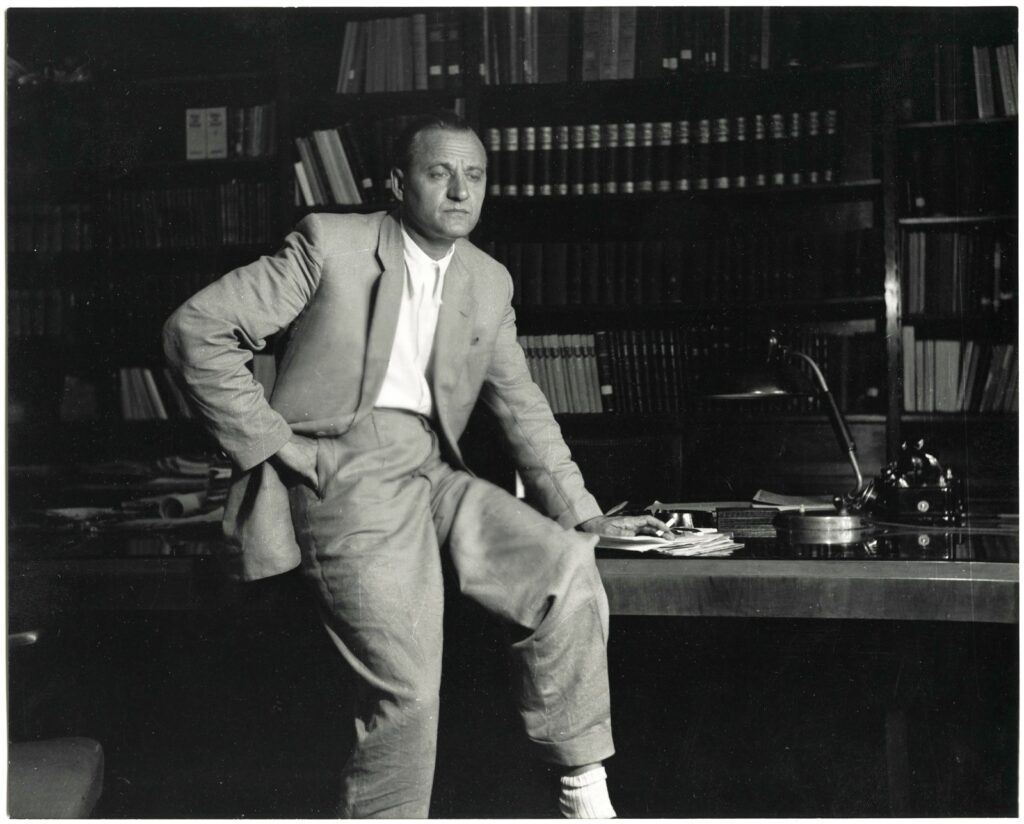

They had two sons, and Eszter Pécsi worked tirelessly before, during, and after their births. She drove her sports car from their Bauhaus-style villa in Óbuda to construction sites and caused quite a stir, also in the press of the time, with her unusual life path and with her bob haircut. The couple’s joint work is the villa on Bajza Street, which now functions as the Museum of Hungarian Architecture, designed for the famous singer of the time, Rózsi Walter.

‘Once I have completed the calculations and prepared the detailed plans, and the work begins, I exercise constant supervision and thus spend most of my time in the buildings and in my small sports car. I enjoy driving. I love speeding past my smaller or larger reinforced concrete children, which are scattered throughout the city, but what I love most is going home to my sons to do math homework or review Latin conjugations…Just because a person happens to be born a woman, she has to work as if life had destined her to be a man…My husband is an architect and we often work together. I love working with him; we always understand each other.’

Eszter Pécsi’s nickname was Eta, and everyone referred to her husband as Yusuf. Yusuf was an uncompromising, courageous man who, in 1944, was able to rescue several people from the Gestapo through his decisive actions. During the most difficult times, the couple became a hiding place for the persecuted, among others, for Tamás Major.

There was no need for private architectural firms in the new system that emerged after the war, so Eszter Pécsi took a job at the Design Office of the Ministry of Metallurgy and Mechanical Engineering, where she was criticized for not showing sufficient enthusiasm during the mandatory morning singing of revolutionary songs. An even greater crime was that she and her husband had participated in the 1956 Revolution, and Fischer had even played a role in Imre Nagy’s government as a committed social democrat. One of their sons was already living in America at the time, and Fischer insisted that his wife also emigrate, as he did not want her to be used to blackmail him during interrogations.

The couple was then separated for a long time. Eszter Pécsi first lived and worked in Austria, then moved to the United States. In 1965 she received the Structural Engineer of the Year award for a special procedure she developed for the foundations of the tower blocks at Columbia University on the banks of the Hudson River.

Meanwhile, her husband repeatedly applied for an emigration passport but was only able to follow her in 1964. He did not achieve the same level of success as Eszter Pécsi, but he cared for his wife, who was left paralyzed after a stroke in 1970, for five years.

Fischer moved back to Hungary in 1978, lived through the regime change, and died in 1995. His wife’s ashes had already been brought home to the Farkasréti Cemetery by then.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.