The following is an adapted version of an article written by Lázár Pap, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

America—the new world, the land of opportunity, the land of the free. In the 19th and 20th centuries, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians left their former lives behind to cross the Atlantic and try their luck Far Far Away, that is, ‘Beyond the Óperencia’, as Hungarian fairy tales go. In its series, Magyar Krónika looks at the meeting points of America and Hungary through the Hungarian diaspora living in the US. In this section, let us go on with the story of Hungarian American newspaper owner Joseph Pulitzer, whose newspaper played a leading role in stirring up readers in the run-up to the Spanish–American War.

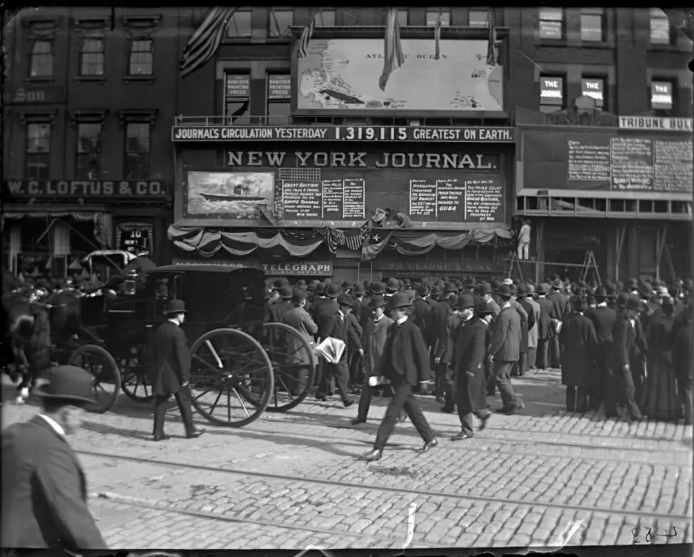

By the last decade of the 19th century, The World, led by Joseph Pulitzer, had become the largest and most important newspaper in the United States. It had 1,300 employees, operated on an annual budget of $2 million, and was the first in America to print a colour Sunday supplement. The Sunday World, the newspaper’s Sunday morning edition, had a circulation of 450,000 copies, making it the most popular Sunday newspaper in the country.

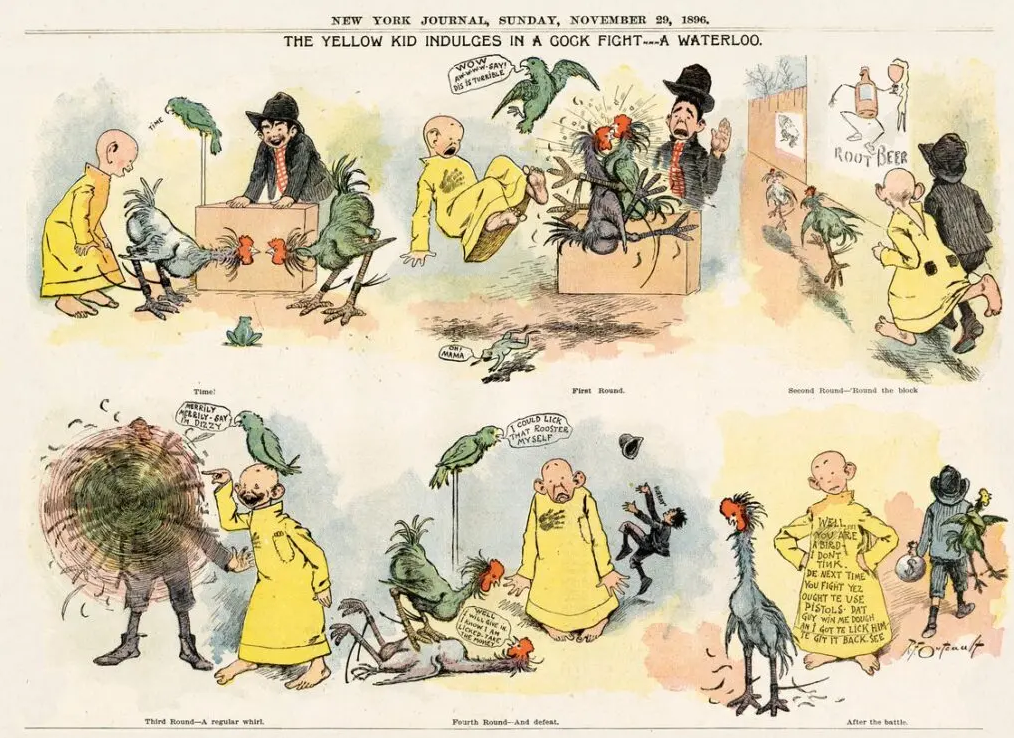

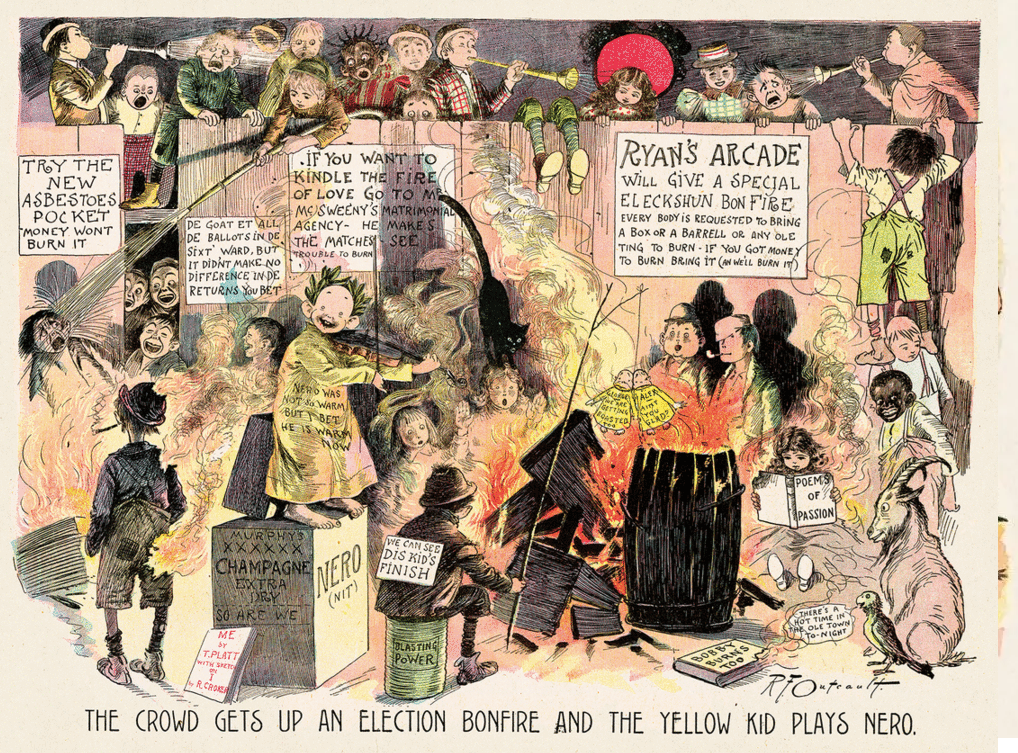

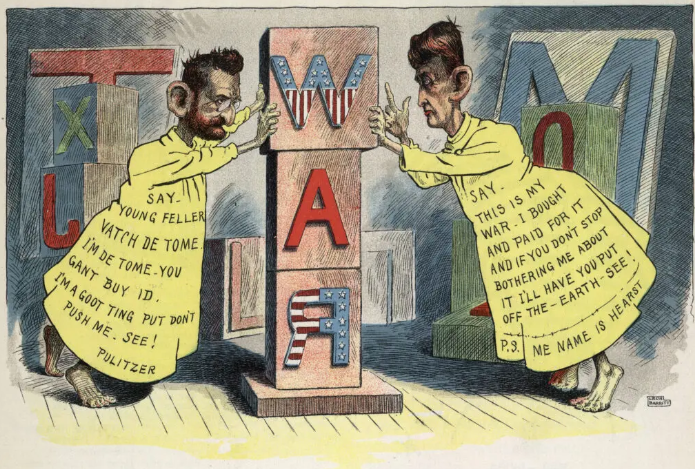

However, as the turn of the century approached, Pulitzer found a rival in William Randolph Hearst. The competition between the two gave rise to the ‘yellow press’ that defined the era, which could perhaps be most simply described as sensationalism. The origin of the term will be explained later.

Hearst came from a wealthy mining family in California. In the 1880s he worked as a reporter for The World, then took over the San Francisco Examiner from his father. Later, in 1895 he bought the tabloid Morning Journal, which he renamed New York Journal. He basically followed Pulitzer’s principles but tried to surpass him in terms of both content and form.

Unlike The World, the New York Journal wanted to appeal to the less educated, lower-middle-class workers and the poor, so it adapted its style accordingly. The press war between Hearst and Pulitzer began in the Sunday editions, with the former luring the editors of The Sunday World to his publication. Hearst’s audacity went so far as to set up his office in Pulitzer’s headquarters, in a space rented by the San Francisco Examiner. Of course, the Hungarian-born media mogul did not tolerate his challenger’s insolence for long and kicked his rival out of the building.

‘The press war between Hearst and Pulitzer began in the Sunday editions, with the former luring the editors of The Sunday World to his publication’

In any case, Hearst was determined to knock his opponent off his throne, and he stopped at nothing to achieve his goal. He unscrupulously copied Pulitzer, initially even taking some of his news stories from him, but he only followed the formal elements of ‘innovative journalism’ and did not want to meet its quality requirements.

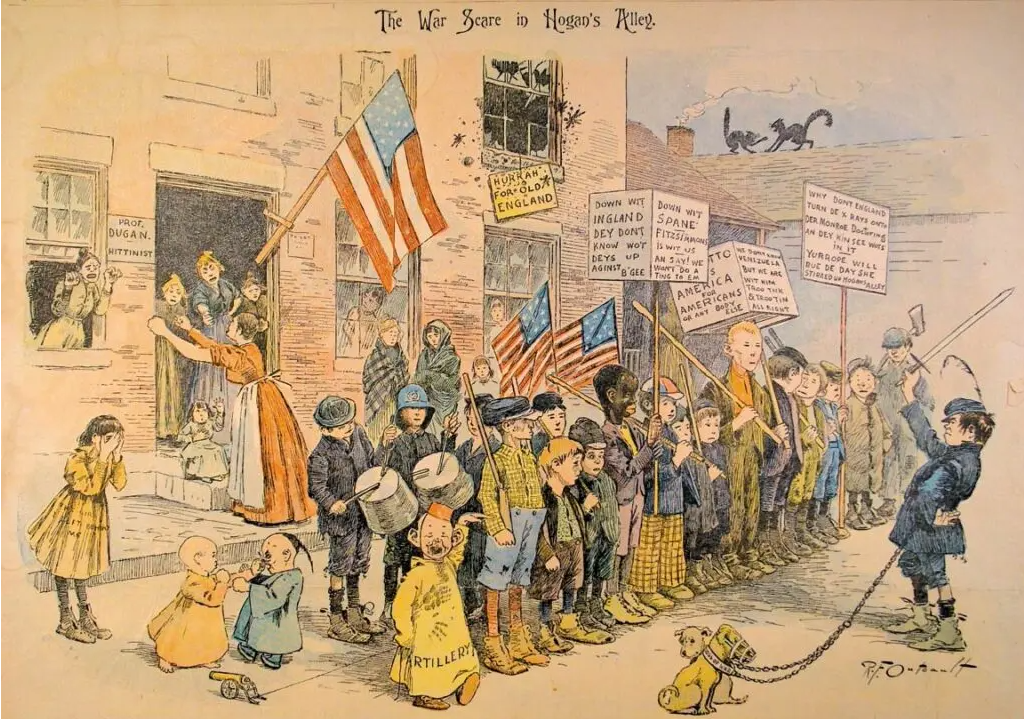

He increased the font size, used more illustrations, and his financial resources proved to be virtually inexhaustible. He sold his paper for just one cent and placed increasing emphasis on entertainment. He managed to sign with cartoonist Richard F Outcault, again from The World, who brought with him his popular character, the Yellow Kid. The stories of the suburban rascal in his yellow sackcloth clothes, which often took on a socially critical tone, became extremely popular.

Following in Hearst’s Footsteps

Pulitzer wanted to keep up with the increasingly popular Journal, so he too gave more and more space to sensationalism. Circulation increased for both papers, but the Journal’s growth proved unstoppable. Pulitzer found himself in a paradoxical situation: in order to stick to his principles (public service, education) in the future, he needed high circulation, but this meant abandoning his principles.

The result of the competition was that Pulitzer’s press lost its prestige and sank to the level of its rival. The most striking example of this was the newspaper’s activity prior to the Spanish–American War.

The basic conflict was the Cuban uprising. The Spanish government appointed the famously hard-handed General Weyler to lead the colonial island in order to quell the rebellion. The Cuban uprising was supported by public opinion and the press throughout, while the government, led by Presidents Cleveland and then McKinley, pursued a neutral, cautious, and prudent policy.

‘The result of the competition was that Pulitzer’s press lost its prestige and sank to the level of its rival’

The latter was forced to abandon this policy when the USS Maine warship exploded under suspicious circumstances in the port of Havana. After that, the leadership was unable to keep the emotions in check and, complying with the will of the people and Congress, declared war on Spain on 23 April 1898.

The Flagships of War Propaganda

Even before his rivalry with Hearst, Pulitzer had sympathized with the Cuban uprising, but in the heat of the competition, his newspaper became one of the flagships of war propaganda.

Following the path laid out by the Journal, The World also took increasingly provocative action ‘in the interests of the Cuban people’. Like Hearst, they sent reporters to Cuba, who sent back a series of unfounded but sensational reports.

Among other things, The World launched a series of articles on the background to the situation in Cuba, illustrated with dramatic images. The first part discussed the ‘horrible history of Old Spain’. In addition, famous reporter Nellie Bly announced in the newspaper that she was organizing a volunteer group of women to join the Cuban rebels.

They continuously reported on Spanish atrocities, illustrating them with drawings depicting the massacre of unarmed Cubans. Sometimes they even used iron neck braces used for executions to illustrate information from rather vague sources. President Cleveland tried to calm things down, but the press was all over him.

The turning point came with the mysterious explosion of the USS Maine, after which The World and the Journal tried to outbid each other in putting pressure on the political elite to declare war—and they finally succeeded.

The Consequences of the War

The Spanish–American War was decided before it even began. The modern ships of the United States quickly defeated the weak Spanish fleet, and the Treaty of Paris marked the end of the Spanish colonial empire. The United States thus gained control over the Philippines and, under the terms of the peace treaty, became the protectorate of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii.

The ‘yellow press’ era had a negative impact on Pulitzer both financially and in terms of prestige. He incurred enormous expenses in his rivalry with Hearst. After the war, he ordered a return to the original principles and a renewed focus on reliability and credibility. By 1901 The World had completely shed the characteristics of the ‘yellow press’, but it still had to wait to fully restore its prestige.

You can read about Joseph Pulitzer’s further adventures in Part VII.

This article is based on András Csillag’s work titled Joseph Pulitzer and the American Press.

Read the previous parts of the series below:

Click here to read the original article.