The following is an adapted version of an article written by Lázár Pap, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

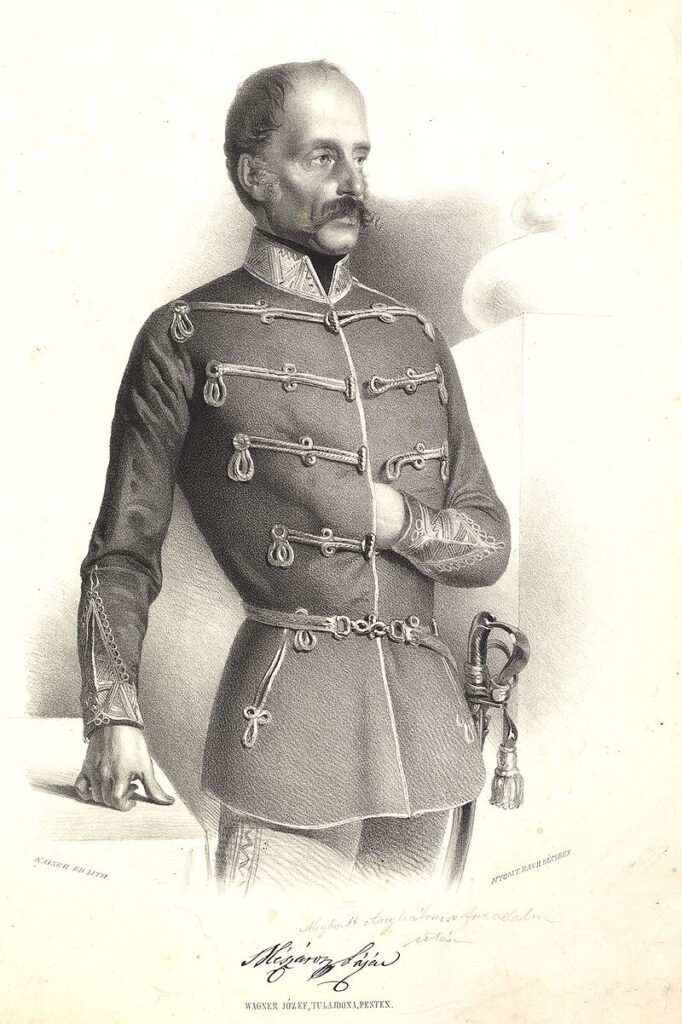

America—the new world, the land of opportunity, the land of the free. In the 19th and 20th centuries, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians left their former lives behind to cross the Atlantic and try their luck Far Far Away, that is, ‘Beyond the Óperencia’, as Hungarian fairy tales go. In its series, Magyar Krónika looks at the meeting points of America and Hungary through the Hungarian diaspora living in the US. This part will be about Lázár Mészáros, former Hungarian Minister of War, who tried to make a living as a farmer growing melons in America. However, the scholar soldier’s attempts were unsuccessful, so he eventually became a private tutor.

Few people know that Lázár Mészáros, Minister of War in the Batthyány Government, was a passionate melon grower. The highly educated soldier spoke seven languages and, in addition to military science, was also interested in history, literature, philosophy, chemistry, and agriculture. He sought to apply his knowledge in the latter field overseas, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves too much.

Lázár Mészáros was born into a noble family in Baja in 1796 and was completely orphaned at the age of four. He was taken in by his maternal uncle, who was a parish priest, and his education was undertaken by the local chaplain. He learned to read earlier than his contemporaries and was extremely interested in the sciences. However, his attention gradually turned to the Napoleonic Wars, which dominated the era. In 1813 the adventurous young man enlisted as a soldier while in his second year of law school.

Thanks to his prior training, he was able to begin his service as a first lieutenant, and after three months of accelerated cavalry training, he quite quickly found himself in the thick of the campaign against Napoleon. After the Battle of Leipzig, he took part in the pursuit of the retreating French army and then was tasked with securing supply lines in southern France.

After the war, he was transferred to Újarad (now Aradul Nou, Romania), but following Napoleon’s return, he was sent to the Italian theatre of war again, where he took part in battles and was also present at the capture of Naples. Until the outbreak of the 1848 Revolution, he served with his regiment mainly in Italy. Recognizing his talent, he was promoted to colonel and then regimental commander.

Even during his military service, he indulged in one of his favourite hobbies, pomology. Between 1816 and 1829 he was also involved in melon breeding and cultivation in Slavonia. He referred to himself as a ‘melon grower’ who ‘loved the fruit in question and grew a lot of it, and good melons at that’. He wrote with particular pride that he had successfully tried grafting Greek melons onto pumpkins in Slavonia in 1826–1827, because, exceeding half the size, he obtained Greek melon-shaped pumpkins, which were a delight to the eye. He was further delighted that ‘Captain Lázár Mészáros’s Slavonian melon variety had retained its goodness so well since 1829’.

‘Even during his military service, he indulged in one of his favourite hobbies, pomology’

News of the 1848 Revolution reached him in Italy, and the Batthyány Government had difficulty finding a minister of war, as political appointees were out of the question due to the sensitivity of the area, while Hungarian officers serving in the imperial army rejected them. At Kossuth’s suggestion, the choice fell on Lázár Mészáros, who was known for his reformist views and corresponded with Széchenyi, among others. He was also a recognized figure in the scientific field and was elected a corresponding member of the Hungarian Scientific Society in December 1844, partly on Széchenyi’s recommendation.

Mészáros learned of his appointment absurdly, from Italian newspapers, so he did not really have a chance to consider it. He finally took up the position at the end of May 1848 but had to contend with constant difficulties. Some of the imperial officers refused to obey orders, and as the war of independence progressed, the duality of loyalty to the revolution and the government on the one hand and to the emperor on the other caused increasing tension within them.

In addition to his ministerial position, at the end of the summer of 1848, he served for a month as commander-in-chief of the Hungarian army in the south in the battles against Croatian Ban Jelačić, returning to the capital only at the end of September. After the government resigned, he remained in his position and became a member of the National Defence Committee, but by then, he was increasingly torn between his loyalty to the court and the revolution, so he repeatedly submitted his resignation, which was not accepted for a long time. At the end of the year, he served as commander of the Upper Hungarian Army Corps but was dismissed after his defeat near Kassa (now Košice, Slovakia).

Mészáros, who had already been promoted to lieutenant general, did not perform any ministerial duties after the Declaration of Independence was issued. After Görgei was removed from office, Kossuth appointed him commander-in-chief, but the officers did not obey him, so he resigned from his position.

At the end of the war of independence, he continued to assist in the fighting as chief of staff to Henrik Dembinszky and was present at the final defeat in Temesvár (now Timișoara, Romania). After the Surrender at Világos, he emigrated to Türkiye with Dembinszky and Kossuth. From Asia Minor, he first went to England, then to France, and then settled for a time on the island of Jersey, which belonged to the former.

Finally, he decided to try his luck in America. Together with his companions, Colonel Miklós Katona and Captain Lajos Dancs, he bought a farm in Scotch Plains, New Jersey, where they began farming but encountered difficulties on several occasions. In March 1854, for example, their house burned down. Mészáros himself was in the house at the time of the incident, so Katona and Dancs rescued him and tried to save his belongings from the flames, but his memories of Kütahya, his Hungarian money, and the furniture he had brought from home were all lost.

‘He bought a farm in Scotch Plains, New Jersey, where they began farming but encountered difficulties on several occasions’

In his letters, he wrote the following about his time on the farm:

‘Making manure is not so much difficult as it is expensive, because here they use lime, ash, gypsum, salt, everything. Guano is the best; for four thalers, you can fairly fertilize an acre with guano.

The horse and cow have already produced fifty cartloads of manure, because a layer of manure was covered with a little burnt lime, then soil or turf, then salt, as this is cheap here…I also have mud, because I have a swamp, and when I drain it, I will use the mud to grow my melons next year.

That’s enough for now; more another time, because I’m building a house, even though it will cost 160 thalers more than was originally planned.’

He explains the following in a letter to his brother, Antal Mészáros, shortly after the fire. In it, he also mentions his plans to continue growing melons in the New World: ‘Don’t think that I am without work, because there are three of us; I take care of the chickens, the garden (I mean the vegetable garden), and milking; Miklós Katona, my old follower, takes care of the horses and cooking; and a fellow named Dants also works with us. These two are younger, so they do the heavier work. There is digging, hoeing, and plenty of farm work, so I can only write on Sundays.’

He wrote about his old passion, melon growing, in several letters, and also reported on the many circumstances that forced them to give up farming after a while.

‘Here comes the rain. It hasn’t rained since 15 July until last Saturday, 9 September. Everything has dried up so much that even if I threw myself into it, I wouldn’t get 100 thalers for it; my potatoes are like walnuts, my corn cobs are only half full, and out of 2,000 cabbage heads, there will be maybe 100 small heads. There will be no yellow melons, the Greek melons will not ripen, there will be perhaps 6 bushels of beans, and the same amount of buckwheat. Added to this is the repercussion of the Eastern European question, which has drained money from here; then there is the good harvest there, which means that no money is being sent for food, resulting in the stagnation of all factories and businesses here due to the high cost of money; and the high cost does not promise the brightest future, but promises misery, which we are already in. So, we must endure, we must suffer, and so I say Amen,’ he wrote in a letter to his brother.

After their farm went bankrupt, he became a private tutor near New York, but he never gave up gardening.

‘Although my lessons last until 4 in the afternoon, they still leave me enough time to cultivate one-eighth of an acre of garden, which they gave me. In it, I will experiment with the “Passionate Melon Grower” (Editor’s note: a reference to Gusztáv Szontágh’s book on melon cultivation), the most famous melon grower in Heves, with his yellow and Greek melons, and with a French variety called “twenty-eight days”. Here, there are only tied (Hungarian “cserhajú”) Dumlek varieties, and since they are sold according to measure, they grow small varieties, which are good but not special,’ he also reported to his brother.

Finally, in 1858 he received citizenship, so he hoped to see his homeland again. He returned to Europe, but on his way to Geneva, he fell ill in Eywood, England, and died on 25 October.

Read the previous parts of the series below:

Click here to read the original article.