The following is a translation of an article written by Lázár Pap, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

His work is like an investigation: the archaeologist visits the site and then tries to put the pieces of the puzzle together based on the evidence found.

Archaeologists’ task is not easy, as they have to unravel hundreds or thousands of years of history based on fragmentary information. We have looked at the evidence and where the investigation starts when excavating an Early Antiquity cemetery.

The vast majority of excavations are done before some kind of construction or investment. These works move the earth at great depths, so archaeologists have a good chance of finding interesting sites that hide the treasures of our past, the relics of our common culture. Specialists often find cemeteries; graves first present themselves as dark spots to the trained eye. This was no different in 2021–22, when the Janus Pannonius Museum and Ásatárs Ltd excavated the site on the outskirts of the village of Babarc in Baranya County, in connection with the construction of the M6 motorway. Then, an Early Avar cemetery was uncovered on a three-hectare area of loess moorland rising from the Danube.

Archaeology has changed a lot in recent years, with the advent of photogrammetry, for example, alongside time-consuming traditional excavation methods. This means that, for example, drone images can be used to create an image-based virtual environment in which specialists can take measurements. In short, it is easier to determine the extent of the areas to be excavated, to see the topography, and, as the work progresses, to see the location and size of graves, ruins, and finds in relation to each other. In addition, the use of other three-dimensional imaging methods, geographic information systems, precision geodesy, and detection instruments is also part of the toolbox of modern archaeology. Once a pit has been excavated, detailed photography, description, and drawing documentation are carried out, followed by a geodetic survey. Only then are the contents of the graves excavated, and every detail is recorded, such as the size of the objects and their relationship to each other, as hundreds of objects can be found in a single cemetery grave.

At the museum in charge, the restoration, inventory, digitization of drawings, and the creation of an accurate map of the cemetery will begin. The investigation then enters a new phase: the ‘detectives’, that is, the archaeologists, begin the scientific work of interpreting the evidence found.

The rich and unique archaeological finds of the Babarc cemetery are very rare in the Carpathian Basin. By rich, we not only mean the gold objects buried next to the deceased, although there was plenty of that too, found in every grave, and in some places, more than one. As for coins, 13 Byzantine gold coins were found in 11 graves. Some of these were worn pierced around their necks or lying as obelisks next to the skulls of the dead. The latter phenomenon has its roots in antiquity, when payments were left in the mouth or hands of the deceased to Charon, the ferryman of the underworld. The custom was adopted in many parts of Eurasia, and in the early Avar period, coins were probably placed in the graves with this intention.

‘The rich and unique archaeological finds of the Babarc cemetery are very rare in the Carpathian Basin’

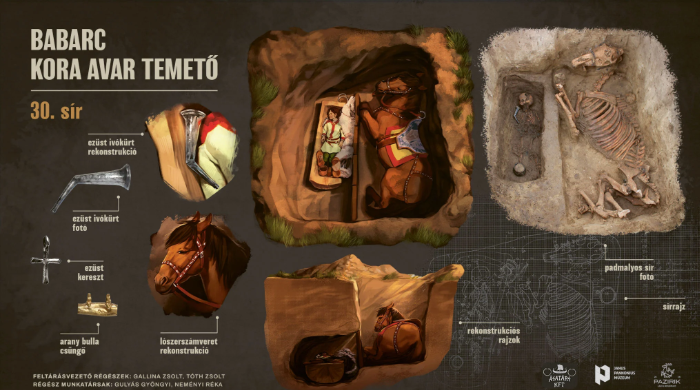

The 44 tombs excavated also yielded a large number of other precious metal objects, jewellery, weapons, and ornate harnesses. Most of the men interred were buried with weapons, often fully equipped with iron, silver, or gilded bronze belts, swords, spears, and bows. In addition to their own material culture, the artefactual material—in weaponry, costume, and jewellery—shows Byzantine, Merovingian, Germanic (Lombard), and local influences. In keeping with the custom they had brought from their native land, their harnessed horses were often laid beside them in a hollow separated by planks. This type of composite grave is called a cubicle grave, or a podmol (borrowed from Bulgarian) grave, depending on where the dead lie. If a space is made for him at the shorter end, it is called a cubicle grave; if at the long side, a podmol grave. Remains of horses, sheep, goats, poultry, and cattle have also been found next to the dead. The custom of separate horse graves may indicate the adoption of a Germanic rite.

At Babarc, the burial order shows a unique pattern, with graves not arranged in rows but scattered, in small groups or solitary. In some parts of the cemetery, archaeologists have discovered sacred spaces and traces of funerary feasts, as well as a chest with arrowheads. It is possible that these squares were used as symbolic tombs to commemorate warriors who died in distant places during the campaigns, but it is also possible that they played a role in the burial rites. The food and drink offerings, the funerary gate, and the traces of the aforementioned ‘sacred grove’ all suggest that, despite the diversity of the finds, the Babarc community had conservative burial customs. The steppe people believed that the soul of the deceased lived on in the earth, even if only for a short time, and therefore left food remains and sacrificial objects near the grave after burial. They tried to prepare the dead for the journey to the afterlife as thoroughly as possible, one might say lavishly. As a sign of this, the wealthier corpses were accompanied by whole horses, not just body parts, just as by the Hungarians, who were more practical in their approach.

Zsolt Gallina, archaeologist and head of Ásatárs Ltd, says that previously it was thought that only one or two generations had used the cemetery. On the contrary, it seems, in line with the dating of Byzantine gold coins, that at least three or four, perhaps even five generations, were buried here. It is important to note that the men always remained local in the community, while the women often came from elsewhere. Nomads did not marry relatives and sometimes brought wives from abroad. A patriarchal society with female domination is the best way to summarize the phenomenon, the expert points out. It is also possible that the Germanic influences seen in the graves may have been brought to the community by women. The discovery of female corpses buried according to Eastern European customs, but in Germanic dress, could be an indication of this. This theory is also supported by the fact that nearby, at Kölked, there were Lombards with whom they may have married for diplomatic reasons. It is assumed that they were settled near the Germanic peoples to keep them at bay. According to Zsolt Gallina, based on their burials, the Babarc community, which was subjected to the Avars, is probably related to other Eastern European nomads who settled in the Transdanubian region, but genetic studies will prove or disprove this.

The Babarc community would have undergone significant changes if its members had remained in the area until the late Avar period, as they were constantly changing in time, fashion, and were exposed to Germanic and Byzantine influences, but around the middle of the 7th century, they disappeared overnight. The period saw the upheaval of the Avar Khaganate peoples due to the Onogur immigration, so it is possible that they were resettled elsewhere. Of course, it is also possible that they were subjugated by the Onogurs and that the remains of their impoverished descendants will be found in a Late Avar cemetery, the archaeologist concludes.

Digging on the World Wide Web

The Pazirik Studio produced reconstruction drawings of the ancient tombs around Babarc in 2023. They have also created an ‘animate on scroll’ (AOS) page to explain the interpretation of the reconstruction and the background of the archaeological work, an interactive interface that can be operated with a mouse scroll. The studio’s work won the education category of the Website of the Year competition, as well as became the absolute winner.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.