The Tragic Death of István Horthy

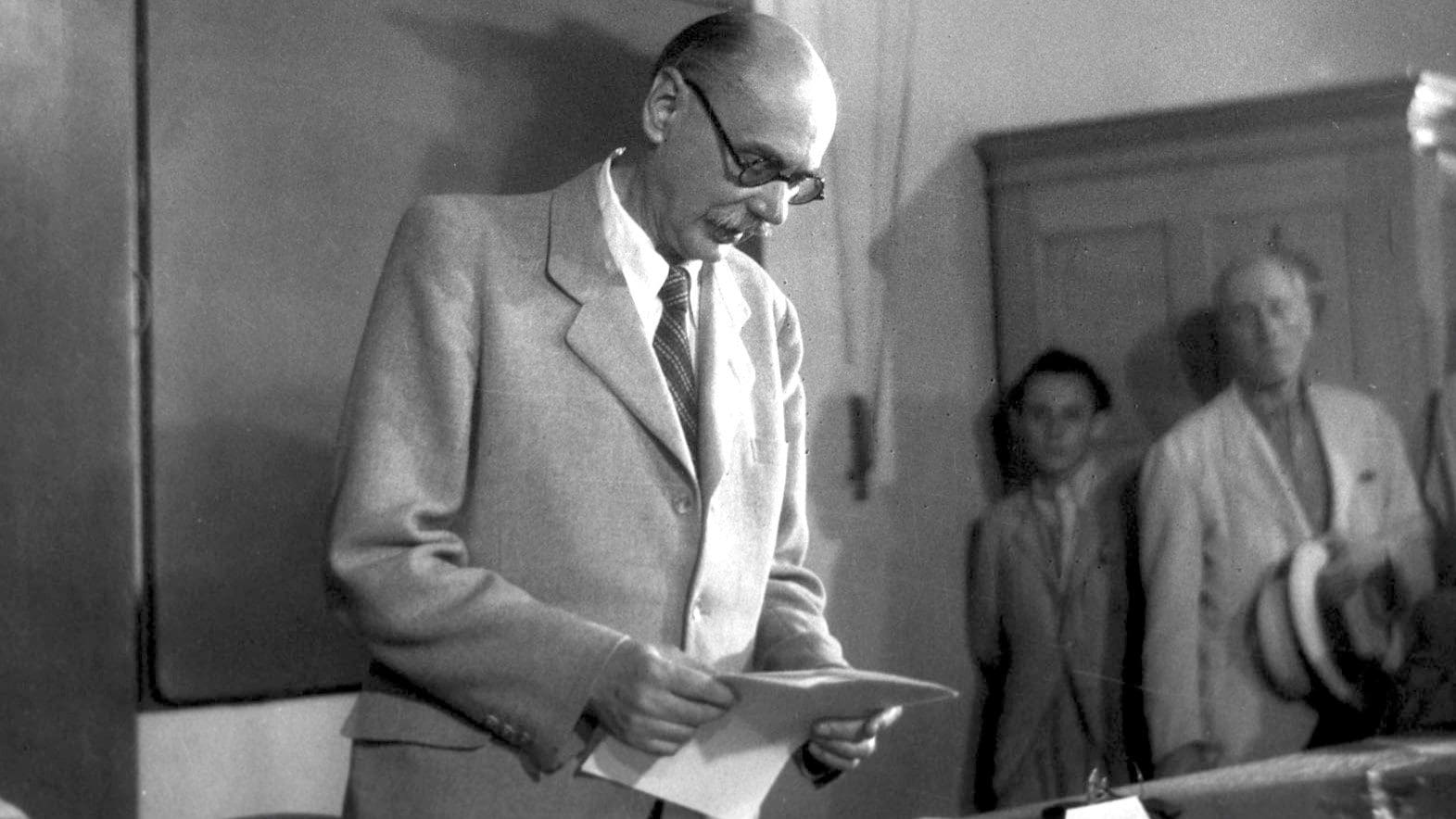

István Horthy, the son of Miklós Horthy, lost his life in a plane crash on the Russian front barely six months after he was elected Vice Regent of Hungary.

István Horthy, the son of Miklós Horthy, lost his life in a plane crash on the Russian front barely six months after he was elected Vice Regent of Hungary.

Since the regime change, we have had eight heads of government, of whom only Viktor Orbán has had more than one term. With his current term running until spring 2026, he has every chance of becoming a historical record holder after 16 years in power.

In her address marking Roma Holocaust Memorial Day, Fidesz MEP Livia Járóka said: ‘Almost 80 years later, it is still clear that what happened at the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp was genocide and a series of crimes against humanity in which innocent European citizens were exterminated on the basis of an exclusionary ideology whose only purpose was organised destruction.’

‘Szekfű described “capitalism” as “having grown in size over time, becoming a more and more fearsome monster, creating factories and cramming hundreds of thousands and millions of people into the unhealthy, immoral air of smoky cities. And the longer the unrestricted freedom proclaimed by liberalism lasts, the more freely the capitalist big business devours the little ones, the more freely it exploits the economic weaklings, especially the workers.” Szekfű’s book Three Generations, in which he also called for extensive worker protection and the regulation of industrialists by law, bears a striking resemblance to the basic tenets of socialism.’

The book’s greatest value can undoubtedly be found in its historiographical sections, which present the historical assessment of the Soviet Republic and the Horthy system. It is in these that the author utilises the largest literary material and provides the widest overview.

Nagy was a highly controversial figure in Hungarian history, whose assessment is still a source of intense debates…He did stand up for the Hungarian Revolution in 1956—for debatable reasons—; but to portray him as a convinced democrat, or a hero of Hungarian popular representation and individual freedom would be a serious distortion. His legacy must be treated in its proper place: his merits must not be denied, but his sins must not be forgotten.

Bartha highlights that it is a painful phenomenon that the non-Communist Hungarian resisters ‘have been relegated to the no-man’s land in terms of memory politics in the 21st century.’ Hopefully, in the future, more attention will be devoted to the anti-Nazism not only of Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky or Lieutenant General János Kiss, but also that of István Lendvai, István Zadravecz or even Gyula Kornis.

‘Through the gaps in the door, I saw Arrow Cross members leading people to the Danube bank to be shot to death. I also witnessed that those who could no longer walk were shot dead then and there, on the street.’

The research conducted by the Danube Institute contradicts the image of an anti-Semitic Hungary painted by many Western mainstream media outlets. Thanks to the government’s zero tolerance policy, public anti-Semitic expressions are no longer tolerated and Jewish people can freely walk in the streets and worship in synagogues without having to rely on heavy security presence.

Tibor Baranski saved the lives of no less than three thousand Hungarian Jews according to Yad Vashem in Israel, but the actual number could be as many as twelve to fifteen thousand.