In Israel, the resistance fighters executed by the British Mandatory Government who had fought for the Jewish state as part of the right-wing militias Irgun and Lechi are still included in the pantheon of national heroes. The collective name for the 12 members of the organizations is Olei Ha-Gardom, that is ‘those who went to the gallows’. An interesting detail is that while the majority of Hungarian Jews did not take part in the Zionist movement, three of the 12 martyrs hanged—and according to the later “expanded” list, 15—were Hungarian Jews. Most of the Zionist martyrs sent to the gallows were Mizrachi, i.e. Oriental Jews from outside Europe; however, for many of them Hungary was indicated as the country of origin.

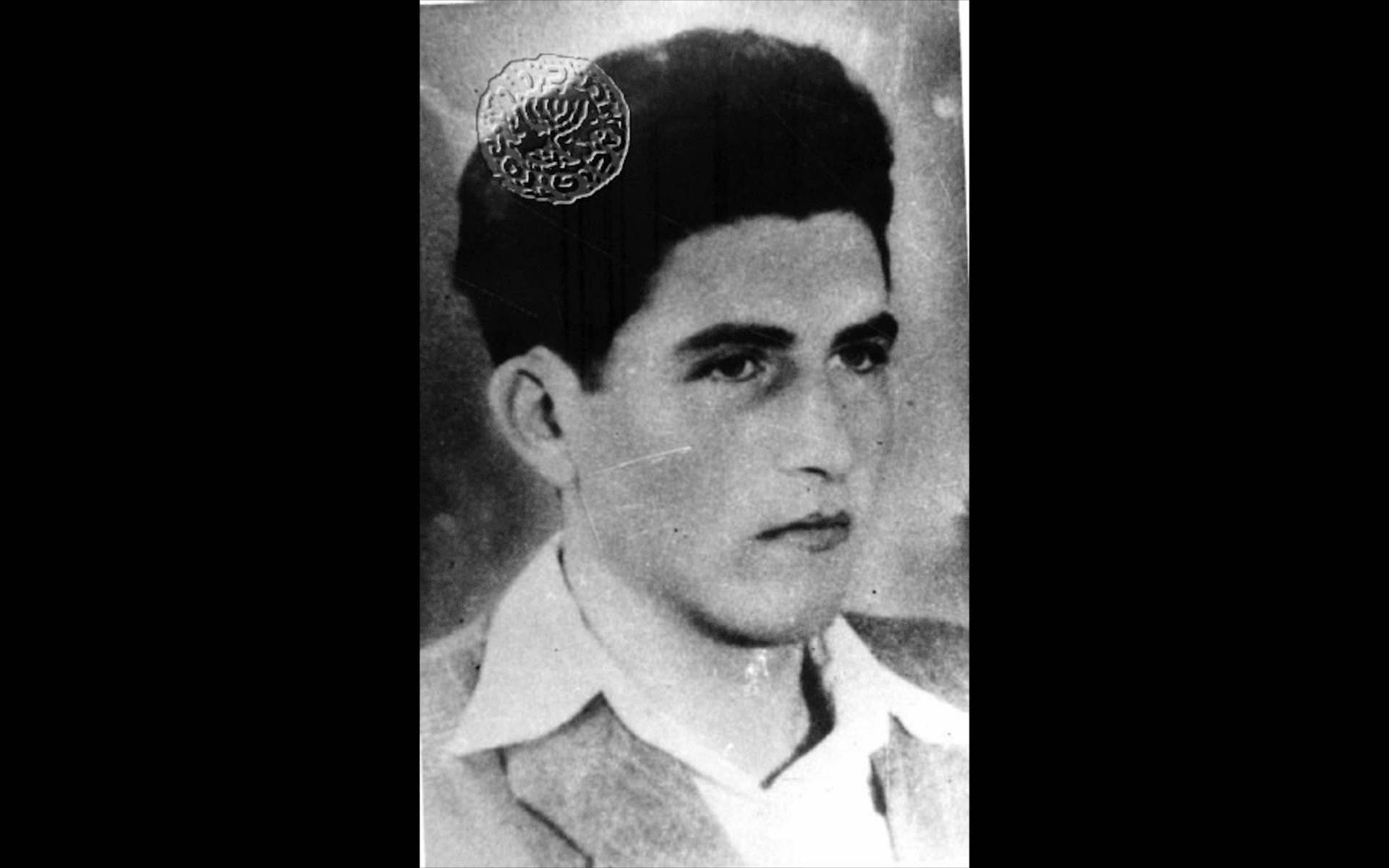

We previously wrote about Dov Grüner, who was caught by the British during an attempted armed robbery of a police station and then executed. The next Hungarian Jew who ‘went to the gallows’ was born in Érsekújvák (Nové Zámky in present day Slovakia; until 1918 part of the Kingdom of Hungary) as Imre Weiss. His father was József Weiss and his mother Heléna Reisner. Recording his name caused problems for later historiography: all of this is a common part of the life journey of Jews from the Diaspora who moved to Eretz Yisrael, the Land of Israel. There are documents, such as his Second World War Hungarian identity card, on which the pseudonym, György Kutas, is listed as his birth name. Some English-language Zionist websites inform their readers that his ‘movement name’ was Erma. This is certainly the result of Imre’s translation back from the Hebrew. However, we can read his Jewish name on his tombstone: Yakov ben Yosef.

Weiss joined the Betar Movement at a young age, which was founded by Vladimir Yevgenyevich Zhabotinsky in 1923 in Riga, Latvia as a secular, right-wing opposite of the left-wing Zionist youth movements. Betar was a discipline-oriented organization, and perhaps it is not surprising that—according to some anecdotes— even as a young boy Weiss was already preparing for the later “wartime” with the Arabs. According to the first Vienna decision, Érsekújvár was returned to Hungary, and Weiss moved to Budapest in 1943 after the death of his father. His plans included leaving the country for Eretz Yisrael, but this was thwarted by the German occupation in 1944. Weiss found himself in the ranks of the illegal Zionist resistance in Budapest, and although the history books did not deal much with the activities of the Betar, it can be said that the actions of this betari rescuer from Érsekújvár were worthy of noting.

He changed his uniform and walked the streets of Budapest, sometimes lifting people from death marches and sometimes from the large ghetto of Pest

Unlike other Zionist resisters, it is not clear where Weiss obtained his Hungarian military and SS uniforms or forged papers. According to survivors, he changed his uniform and walked the streets of Budapest, sometimes lifting people from death marches and sometimes from the large ghetto of Pest. According to an anecdote, on one occasion fake IDs fell out of his bag and this attracted the attention of a Hungarian policeman, but Weiss kept his cool and ordered him to help him collect them.[i] And according to the notes of a member of the revisionist movement, he also visited rural ghettos in disguise and took Jews from there to Budapest, where they were placed in safety.[ii]

He finally left the city on the so-called ‘Kastner train’, as part of the right-wing Zionist group which was given a place on the rescue flight composed mainly by left-wing Zionists thanks to the benevolence of the organizers. The passengers of the train spent some time in Bergen-Belsen before moving onto Switzerland. A survivor, László Löb wrote in his book that the young guards in the camp manufactured primitive weapons and practiced for the Palestinian wars. The mostly left-wing camp residents even named one of their loud, violent German guards ‘Betar’ – borrowing the name from the right-wing movement, clearly an act of mockery towards their conservative Zionist rivals.[iii] Yaakov Weiss, under the name Weiss Emerich, can be found on one of the remaining Bergen lager lists as passenger number 1640 of the Kastner train.[iv]

From the camp, Weiss moved to Switzerland, where he became a student of the University of Geneva and took part in several months of agricultural training,[v] but he soon had enough of this and tried to make aliyah. However, his ship was intercepted by the British navy, and Weiss was imprisoned in the Atlit prison camp in Palestine. The left-wing Palmach militia stormed the prison in October 1945, freeing him as well. Among his rescuers was Avsalom Haviv, who later became Weiss’s comrade in arms in the Irgun right-wing paramilitary group. Weiss moved to Netanya, where he did manual labour—diamond polishing—and attended Betar events in the evenings. It was here that he received the news that his mother and her entire extended family, about 200 people, had been murdered in Auschwitz. His sister, Edit was the only one to survive the death camp. She lived in Karlsbad at the time and was planning her own moving to Eretz Israel.

Their correspondence in Hungarian can be found in an archive in Tel Aviv. In his December1945 letter, he still tries to cope with the loss of their mother. ‘What mother’s death meant to us, I can only now understand with my mind and soul. I try not to think about the past, but you can imagine how I feel. […] I want to cry from helplessness, that I can’t help you in anything, that we are so far apart. You don’t need to explain what it means to be alone, unfortunately I feel it very well too.’[vi] And in another letter, he asked his sister for books: he wanted to read Will Durant and Antal Szerb, preferably all in Hungarian because he did not yet understand Hebrew.[vii] Nevertheless, he wanted to educate himself in order to be a useful member of the community of those fighting for the liberation of Palestine from British rule and the establishment of a Jewish state.

On June 16 1947, Edit Weiss received a letter from her brother. The last time she heard from Yakov was in April, but the letter shed light on the reason for his silence. Yakov joined the illegal Zionist militia Irgun and took part in the siege of the Akko castle prison on May 4. That day, Zionist fighters dressed in British uniforms attacked the fortress once built by the Crusaders, which the British used as a prison. By blasting a hole in the side of the building, they managed to free dozens of imprisoned Zionists, but British soldiers intercepted the two jeeps of the rescue group while they were fleeing. The Irgun lost nine of its men, and three were captured: two Mizrachi Jews – Avsalom Haviv and Meir Nakar – and Yakov Weiss himself.

In the last letter he wrote to his sister, addressed to her in Hungarian as ‘Drága Editkém!’ (‘My dear Edit!’), he explained his reasons for joining the Irgun as follows: ‘We must win, or we will perish, and the future of our entire people will perish with us. That was what put the gun in my hands. I knew this was a fight for our freedom and our future. I was no longer a “stinking Jew”, but a self-aware, fighting Jew who knew why he was fighting. I forgot the feeling when every peasant could spit on me and there was no other way but to wipe the spit and say thank you. That time has passed. We respond to a punch with a punch, and to spit with a spit.’

However, at the end of the brave text, he revealed that he was still a 23-year-old boy. ‘No matter what, I’ll try to behave as Mom would have wanted,’ he promised his sister. In addition to these, he also told Edit to be a ‘proud Jew’ and that she and her relatives should remember their Jewishness, ‘otherwise you will be bitterly reminded of it’ by the outside world. The hard copy of the letter was lost, but it was republished by an Israeli newspaper decades later. The stains on the letter, added the editor, ‘reveal an ocean of tears.’[viii]

Weiss’s case was not helped by the fact that, like other right-wing Zionist fighters, he and his comrades refused to recognize the authority of the British court over them. During the trial, they talked to each other, drew caricatures of the British in the room, or even sang Zionist movement songs. When given the opportunity to speak in his own defense, Weiss addressed ‘the officers of the occupying army’. According to his arguments, British rule in Palestine was illegal, and; therefore, he did not want to assist in the proceedings: ‘This country has been ours since ancient times and will be ours forever.’ What right do they have to condemn ‘an ancient, cultured, freedom-loving people’ who, moreover, themselves conveyed the divine truth to the world?

After that he compared the British laws restricting the immigration of Jews to Hitler’s Jewish laws, and then spoke about his own possible death like this: ‘We are happy because there can be no greater joy than giving our lives for a good cause.(…) Tell your masters: A new generation of the Jewish people has arrived to the land of Israel. A generation that loves life, but loves freedom even more than life. A generation that will overthrow the rule of the Nazi-British, even if they have to give their lives for it. The Jewish people live: and the Jewish state will certainly rise.’[ix]

His words reflect the strong national commitment surrounding the right-wing Zionist movements

His words reflect not only the war atmosphere prevailing in Palestine at the time and the self-awareness of the young man facing the death sentence, but also the strong national commitment surrounding the right-wing Zionist movements. Among the members of the Betar movement, Horace’s line was a common phrase: ‘It is good to die for one’s country’. Yakov Weiss was sentenced to death on June 16 1947.

He may have seen all of the above in a heroic way, but his sister, Edit, not so much. She applied for a visa through a Palestinian law firm and immediately traveled to Jerusalem. Her lawyer, Aser Levitski, obtained the visa on the grounds that Edit’s entire family—apart from her younger brother—became victims of the Holocaust.[x] And Edit herself wrote to the British High Commissioner for Palestine, Sir Alan G. Cunningham, regarding her younger brother: ‘I hope you will understand my suffering. My brother’s fate is now in your hands, and I beg your excellency to spare his life. […] Apart from myself, my brother is the only surviving member of our large family who lived in Czechoslovakia and who were destroyed by the Nazis in various death camps. I myself barely survived Auschwitz. My brother, Yakov […] fought against the Nazis during the war as a member of the Czech [actually the Hungarian Zionist – the Ed.] underground movement. He has many brave deeds behind him, during which he risked his life to save Jews from certain death.‘

‘My only hope in life is him’, she added to her letter, ‘and I have none left if he is lost’. As she pointed out, her brother broke the law because he wanted to help people all his life.[xi] Among the relevant archival materials in Tel Aviv, there is also an artistic petition that asks for pardon for all three Irgunists, but primarily singles out Yakov Weiss. On July 10, lawyer Aser Levitski received a letter in German from a certain S.P. Irsai who promised that he would raise Weiss’s case in the ‘entire world press’ and that the campaign could be successful, since he himself was a prisoner in Bergen, in fact Weiss’s ‘comrade’.[xii] The writer of the letter, István Irsai, was indeed among the passengers of the Kastner train. He became a famous graphic artist in Palestine under the name Pesach Ir-Shai. The drawing made for the campaign can still be read today, with the names of the signatories on it: among them were the right-wing Zionist from Kassa, Lajos Gottesman, the left-wing Zionist from Transylvania, Danzig Hillél, and Ernő Kasztner, the brother of the famous rescuer.

The letter did not affect the High Commissioner, but the fact is that the director of the Acre prison, George Charteton refused to carry out the sentence, which is why he was fired. On the evening of July 28, the three young people were told that they would be executed, and then they were led out one by one at four in the morning the next day. All three went to the gallows singing the later Israeli national anthem, Ha’tikva. Weiss was the last.

Chaim Wasserman, an Irgunist inmate of the prison, later claimed that the boys’ prison had the following inscription on the wall: ‘You can’t frighten the Jewish youth fighting for the homeland with the gallows. Thousands will follow us.’ Behind them was the Irgun crest and their names.[xiii] And among Weiss’s papers, a piece of paper with the Irgun’s coat of arms – Eretz Yisrael Ha’shlema, i.e. Great Israel, and a hand holding a weapon – and the slogan rak kach, i.e. ‘Only Thus!’ is written. Of course, the realization of Greater Israel, which includes today’s Jordan, was not set as a goal by any authoritative Israeli politician, but it sufficiently illustrates the objectives of the competing national movements of the era.

The execution sparked high tensions. On July 11, on the orders of the leader of the Irgun, Menachem Begin, later Prime Minister of Israel, two British officers were kidnapped from the Gan Vered café in Netanya, and after the execution of the three Irgunists, they were hanged in an orange grove. Begin later told journalist Chaviv Knaan that it was ‘horrible’ to sign the verdict, but even more horrifying was the lack of reaction to the execution of the three Irgunists, including Weiss.[xiv]

In any case, it caused a serious scandal in the public life of the time that the Irgun tied an explosive device to one of the bodies, so when they were found and cut down, the body exploded, seriously injuring one of the arriving British officers and depriving the kidnapped soldiers of their final dignity. After the action, the British police stationed in Tel Aviv essentially started a pogrom, to which four Jewish civilians fell victim.[xv]

After the execution, Edit Weiss settled in Cholon after her lawyer, Levicki, obtained a settlement permit for her. His brother’s memory is preserved by a street named after him in Tel Aviv, and in 1982 a stamp was issued with his portrait. Additional streets in Jerusalem and Rison Le’tsiyon, and a monument in Ramat Gan, preserve the memory of ‘those who went the gallows’. Perhaps few in Hungary know that a Hungarian Jew who helped Jews in Budapest during the Holocaust and was later executed by the British is so revered in Israel today.

[i] Jabotinsky Institute (Tel-Aviv, hereon cited as JI), K16-6/4/2, 5.

[ii] Jeshurun Élijáhu, ’Zsidó szabadságharcosok’ (Budapest: Filum, n. d. [originally 1985]), 214.

[iii] Ladislaus Löb, ’Megvásárolt életek. Kasztner Rezső vakmerő mentőakciója’ (Budapest: Athenaeum, 2009), 150–151.

[iv] List of the Bergen-Belsen prisoners who arrived on the Kastner train, 41. (among the papers of Miklós Spéter, a copy in the possession of the author).

[v] JI, K16-6/1, 20-22.

[vi] JI, K16-6/2/2, 17.

[vii] JI, K16-6/2/2. 15.

[viii] JI, K16-6/6. 2-3.

[ix] JI, K4-22/12. 77., 80.

[x] JI, HT13-3/46. 10-11.

[xi] JI, HT13-3/46. 36.

[xii] JI, HT13-3/46. 45.

[xiii] Yehuda Avner, ’Bygone Days: They Went to the Gallows Singing ’Hatikva’,’ www.jpost.com/Features/Bygone-Days-They-went-to-the-gallows-singing-Hatikva, accessed: 22 Aug. 2022.

[xiv] Élijáhu, ’Zsidó szabadságharcosok’, 215.

[xv] Four Jews Killed, Many Injured When British Police Riot in Tel-Aviv. Jewish Telegraphic Agency, 1st August 1947.