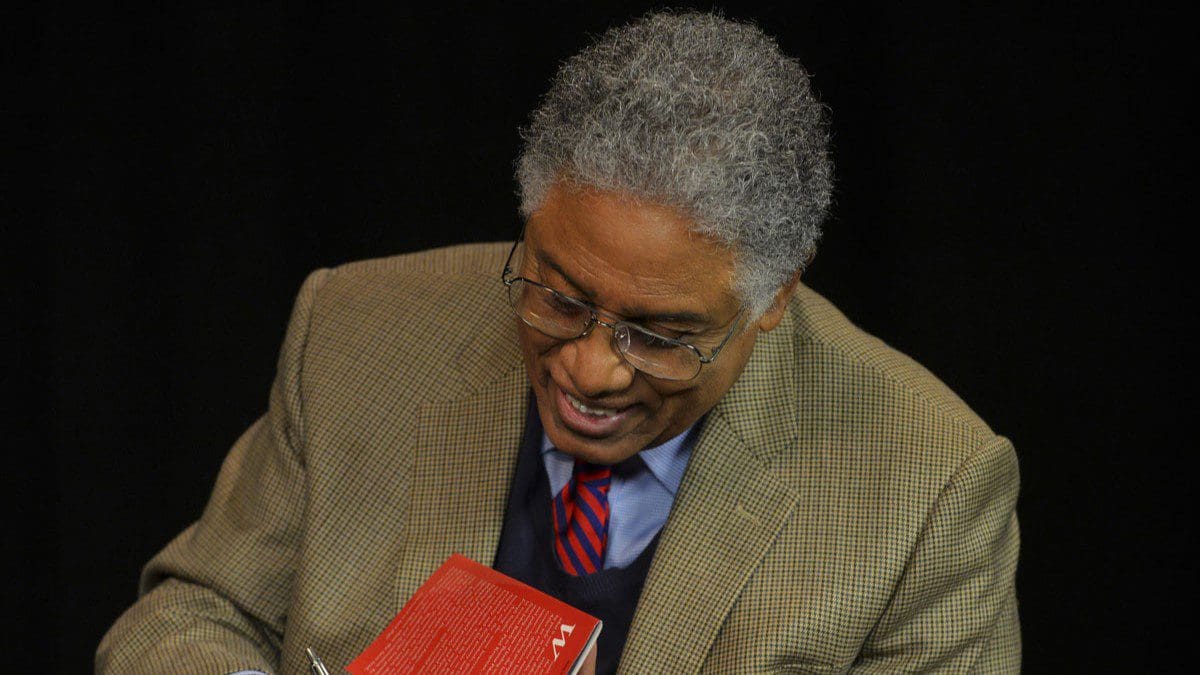

A Review of Thomas Sowell’s book titled Discrimination and Disparities.

Thomas Sowell, a member of the old neoliberal elite mentored by Milton Friedman, has explored the issues of discrimination and state intervention for decades. Sowell, currently a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, is the author of dozens of books including Charter Schools and Their Enemies, which won the 2021 Hayek Book Prize. The African American scholar and writer is the recipient of numerous other awards, including the National Humanities Medal, presented by the President of the United States in 2003.

His 2018 book titled Discrimination and Inequality, recently published in Hungarian by MCC Press, is essentially a critique of the leftist oppressor-oppressed dichotomy. Sowell, himself a former Marxist, argues that the Marxist thesis of exploitation is not an abstract concept, but a view ripe for academic criticism.

Sowell begins his book by stating that there are many explanations for inequalities, which broadly fall into two extreme categories: some believe that inequality is rooted in descent, in genetics, while others believe that the less well-off are exploited by the rich. Sowell believes in neither as an exclusive explanatory factor. Instead, he holds that success depends on a number of preconditions, where even small differences can mean big differences in outcomes.

To underpin his claim, Sowell cites a survey started in the early 20th century, which followed the careers of 1,470 people with IQs of 140 or above for nearly 50 years. The in-depth longitudinal research found that the careers of these individuals showed strong variations, despite all of them being in the top one per cent of society in terms of intelligence. While many became successful, quite a few turned out to be rather mediocre performers, and some only managed to complete secondary school. Meanwhile, two men with IQs below 140 were awarded Nobel Prizes. But there were no Nobel Prize winners among the 1470 people surveyed.

The author concludes that it is clear that other factors, not just intelligence, must play a role.

The cited research identified family background as a major factor. Yet, many continue to argue for a one-factor explanation, believing that privileged status or racial characters are the key. Sowell points out that the crimes of both communism and Nazism are the end result of these misconceptions. Contrary to these views, Sowell highlights the existence of additional factors. He, for instance, reminds that the first-born are generally smarter and more successful than the other siblings in the family—despite having received almost the same upbringing. So different people and different life paths produce very different results.

Historical context is also important: it can lead to rapid rises or falls. The Scots, for instance, did not produce a great thinker until the 18th century, but then with the spread of the English language and the rise of Protestantism this changed, and today we think of them as the nation of James Watt, Adam Smith, David Hume, Joseph Black, Sir Walter Scott and John Stuart Mill. A similar example is Japan, which for a long time was a backward nation, but this was clearly not the result of characteristics of the Japanese as an ethnic group, as they soon made up for their disadvantage. Similarly, Jews did not produce many serious scientific thinkers until their emancipation, whereas today they account for 22 per cent of Nobel Prize winners in chemistry and 32 percent of Nobel Prize winners in both medicine and physics.

Of course, there are also examples of decline: until the 15th century, China was the most advanced country in the world, extensively using iron, setting off on long voyages of discovery, using better ships than Columbus, inventing gunpowder, etc. But in the 15th century, the country started closing up, and its development began to lag behind the rest of the world. Later, the country was de facto colonised—while today, it is a leading powerhouse of economic and scientific progress, but that is a different story.

Sowell also cites the example of maritime countries: he believes that the possibility of maritime transport has always increased the chances of a civilisation’s rise. To this day, land freight transport is much more expensive than sea freight. But distance also matters. Almost all the major ancient achievements took place in the Middle East or the Mediterranean, and they reached, for example, Hellas or Rome much earlier than, say, Scandinavia. ‘By almost any standards, ancient Greek civilization became far more advanced than the societies of the British Isles or Scandinavia,’ the author points out.

But one could also cite the example of age. Middle-aged people everywhere earn more on average than the young or the very old. Sowell asks the rhetorical question: which young people have the experience to become a successful company director or military officer? So the difference in income based on age is not an injustice, but the result of logical considerations.

Although the concept of equality is very popular, surely no one seriously believes that we can all sing like Pavarotti, or be as talented physicists as Einstein.

So we cannot expect to see an equality of abilities materialise.

As for the equality of income, something that socialism experimented with, it has been demonstrated time and again that it does not work. Sowell reminds that today’s woke press incites against big business because it is easier to point to the high pay of a big company executive than to point to an artist who earns even more. But the role of artists cannot be taken over by bureaucrats or politicians, so they are not worth attacking, Sowell suggests.

Ultimately, Sowell argues, single-factor explanations have always been popular, and there have been entire books written on such worldviews. The author cites Hitler’s Mein Kampf and Marx’s Das Kapital as typical examples, although he adds that the latter is a more serious work. But these overly simplistic explanations do not stand up to scientific scrutiny, Sowell concludes.