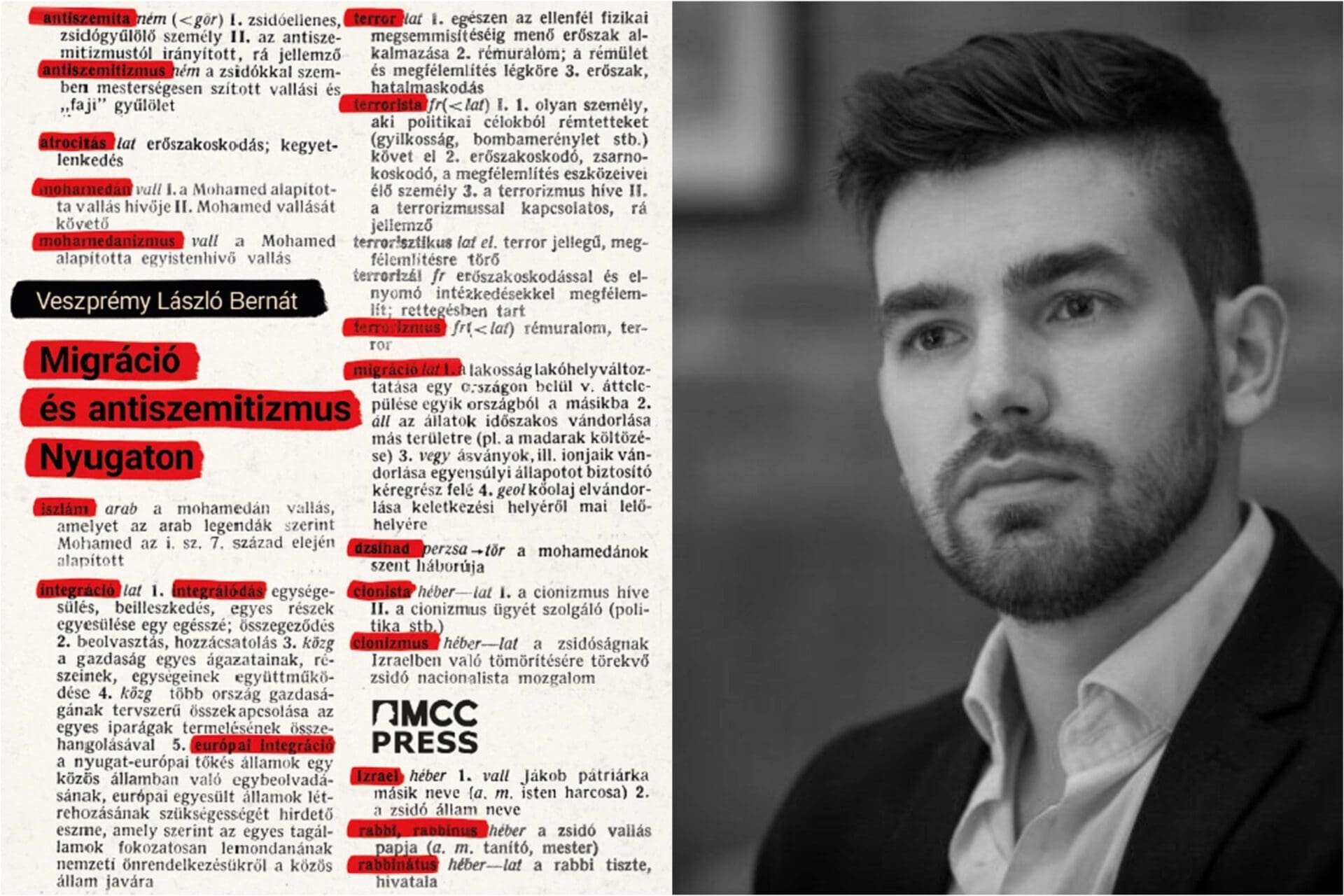

Review of László Bernát Veszprémy’s book Migration and Antisemitism in the West (Migráció és antiszemitizmus Nyugaton, MCC Press, 2021)

In October 2021, something started to move in the right direction. The European Union published its first-ever strategy to combat anti-Semitism. The study cited [in the EU strategy paper] found that 85 per cent of Jews surveyed in various Western [recte EU] countries consider anti-Semitism a serious problem, to the extent that 38 per cent were already considering emigrating because of the increasing number of incidents. But how did Europe, so proud of its tolerance and diversity, get to this point? The answer can be found in László Bernát Veszprémy’s book, which strengthens the academic facet of the Mathias Corvinus Collegium publishing house.

The subject of the book is admittedly very personal to its author, a historian by profession. As a student at the University of Amsterdam, he experienced first-hand that going to the synagogue or even talking about Israel in public is not without risk in the liberal democracy of the Netherlands, where immigrants from different backgrounds can often harass Jews or those they perceive to be Jews, amidst the complicit silence of the majority society. He has published his experiences in the Jewish journal Szombat, on the website of the Jewish Action and Protection Foundation (TEV), and in conservative weekly Mandiner, and has also conducted academic research on the subject. The result is Migration and Anti-Semitism in the West, in which the author explores what Spiegel Online called ‘imported anti-Semitism’ in a 2015 article, and

seeks to answer how mass immigration is linked to the dramatic rise of anti-Semitism in Europe

and looks at how left-wing parties are accomplices in it. László Bernát Veszprémy did not have an easy job. In his research of this narrow topic he could not rely on monographs, studies, or even articles, as Western researchers, fearing political attacks, have been reluctant to address this sensitive issue. What he was left with therefore were studies and surveys that indirectly touch on the subject but which are far from providing a complete picture. And then there is the fieldwork, during which the author had some incredible experiences. ‘During my research, I met threatened communities, worried people, and community leaders who were broken, defeatist or who enveloped themselves in silence. I did not speak to or interview a single person who had a positive view of the future of Western Jewry,’ he writes. To László Bernát Veszprémy’s credit, he does not give way to emotions in his book, neither does he draw unfounded conclusions, and he keeps to the facts and the objective data throughout. He makes it clear that his aim is not to demonize the Muslim population of Europe, nor does he claim that all Muslims are anti-Semitic, but merely to point out a phenomenon that has been swept under the carpet by the political mainstream and academia in the West.

The fact that his personal involvement does not obscure the author’s objectivity is clear from the very first chapter, in which he presents a series of authoritative surveys from 1997 to the present on how different Muslim immigrant groups view Judaism and the state of Israel. These show that, on average, half of those surveyed hold views that make their coexistence with European Jews problematic, to say the least. The available research also shows that this percentage is similar among those who arrived with the 2015 migration wave, mostly because they brought with them the narratives and tropes that are common in their countries hostile to Israel. Unfortunately, thoughts are often followed by actions. The second chapter describes the alarming trend in the number of physical atrocities against Jews. It shows, among other things, that the current conflicts in the Middle East are typically also manifested in the streets of Europe: in 2014, the year of the Gaza conflict, the number of atrocities committed against Jews by young people from immigrant backgrounds increased almost everywhere. Of course, the fact that many countries (including Germany and Sweden) do not keep records of the ethnic origin of the perpetrators makes it challenging to see clearly. But the victims’ accounts are clear: Jewish communities attribute the vast majority of attacks to Muslim extremists. Of course, incidents often go unreported, which means that their number is probably much higher than what statistics indicate. It is also remarkable that the number of right-wing perpetrators has been falling sharply.

The third chapter explores the issue of Holocaust denial. It finds that after 2005, as a result of Israel’s conflicts with Hamas in Palestine and Hezbollah in Lebanon and the rhetoric of former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013),

Holocaust denial has become more prevalent than ever before in the Muslim and Arab world.

As a result, more and more people in the Western diaspora have begun to deny the genocide of World War II, or even to praise the Holocaust, or equate Israel’s policy towards Palestine with the crimes of the Nazis. The author shares the scepticism of European Jewish community leaders and experts on whether educating young people from immigrant backgrounds about the Holocaust, as the German state is trying to do, will make a difference. The question is, of course, whether there is the political will to stop dangerous ideas everywhere. Chapter four concludes that there is little political will on the part of the European left-wing parties. They often have their eye on winning the ‘Muslim vote’, and as a result, they are reluctant to engage in confrontation. The example of the British Labour Party, whose former leader, Jeremy Corbin himself, used anti-Israel rhetoric to win votes, and failed to take action against growing anti-Semitism among his party’s members, is an excellent illustration of this. Of course, the Muslim vote is not only sought after by left-wing parties but also by groups whose base consists of immigrants. The fifth chapter uses the example of DENK, the only European immigrant party founded by Turks in the Netherlands that has managed to get into parliament, to show how incitement against Jews and Jewish organisations can be used to win votes.

However, the rise of anti-Semitism in mainstream politics is evident not only in Europe but also in the US. Chapter six looks at the career of Ilhan Omar, a Somali-born Democrat member of Congress. The author concludes that

embracing the careers of Muslim women is a combination of a progressive message and minority representation for left-wing parties.

This, in turn has led in this particular case to political anti-Semitism moving from the periphery to Congress. Moreover, in addition to her anti-Israel stance, Ilhan Omar keeps reviving old anti-Semitic tropes, questioning, among other things, the loyalty of Jews to the United States. She does all this with virtually no consequences, and the Democratic Party, for the most part, does not condemn her statements.

The seventh chapter examines the interplay between two extremisms, namely Islamist and far-right terrorism, and more specifically, how the European Jewry can be caught between two fires in a quasi-civil war between extremes. The eighth and final chapter, although it deals with an exciting topic that has been little explored in Hungarian, is somewhat out of place and breaks the well-constructed thought arc of the volume. In it, the author, moving away from Europe, looks at Israel’s migration policy, examining the legal and law enforcement measures taken by the Jewish state against African migrants that have been arriving illegally onto its territory since 2012.

László Bernát Veszprémy’s book is a much needed gap-filler, and thanks to its hopefully soon-to-come English translation Western audiences will be able to find out what is happening in their own countries. The book also confronts readers with the fact that it is not nationalism and conservatism, but liberalism and ‘open societies’ that have put Jewish communities at risk.