Our frequent contributor Zoltán Pető’s article in the last issue of Kommentár examines the case of Franz von Papen’s 1934 Marburg Speech. On the basis of the speech, Pető sets out to analyse the anti-Nazi feelings of a lesser known movement, the so-called Conservative Revolution (Konservative Revolution), and, more broadly, of the German conservatives of the Weimar era.

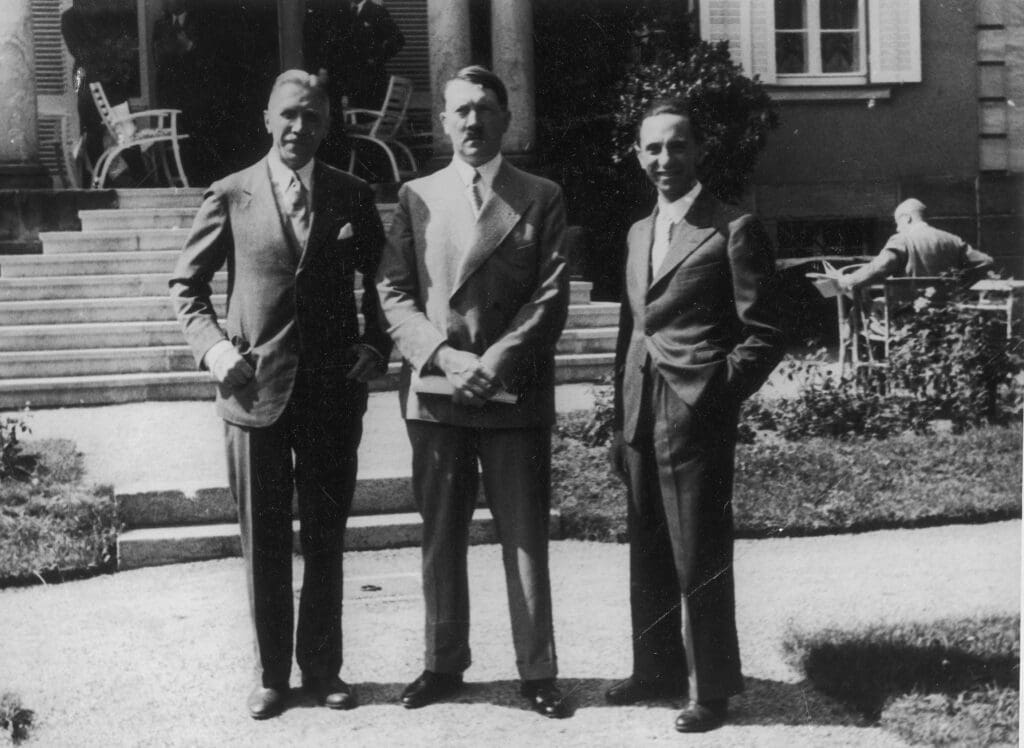

On 17 June 1937, Papen, who was the Vice Chancellor at the time, gave a speech at the University of Marburg, in which he openly criticized Hitler and the Nazis. However, the remarks were not written by ultraright-Catholic monarchist von Papen, who had also served as Chancellor for a brief period of time in 1932 and had in fact been an enabler of Hitler.

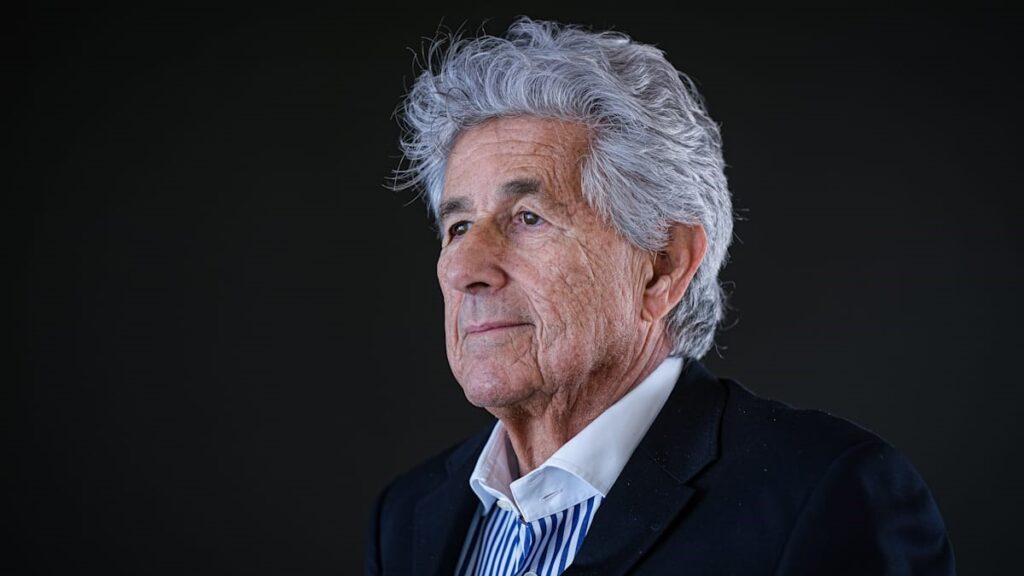

The speech was drafted primarily by Edgar Julius Jung, a German lawyer,

one of the leaders of the Conservative Revolution, who was soon afterwards murdered by the Gestapo during the Night of the Long Knives. The speech was a brave, but unsuccessful attempt to critique Hitler from a conservative standpoint.

Pető’s article begins with presenting the Conservative Revolution to the readers. Comparing it with National Socialism (Nazism), he notes that the mostly left-wing critics of the conservative movement were not entirely misguided when likening the movement to Nazism, as it indeed shared similarities with Nazi ideology. However, Pető also points out that the two ideological streams diverged on key points. According to Pető, the Conservative Revolution was an ideological answer to the Weimar Republic by the young generation, disaffected by the relativism, modernism, and liberalism of the nineteenth century. In fact, one of the main criticisms of these conservatives against National Socialism was that it was

essentially a nineteenth century movement.

According to Pető, the conservative revolutionaries described it as relying too much on, and fascinated by technological progress, furthermore, believing in anti-Christian ideas like Social Darwinism, and compromising itself by taking part in parliamentarianism. Pető also highlights the fact that the conservative revolutionaries opposed the neo-pagan and antisemitic ideas of the Nazis. While some representatives of the Conservative Revolution, for example Carl Schmitt, supported Hitler, most of them, for instance Ernst Jünger, a German novelist and essayist, and Edgar Julius Jung, the author of the Papen speech, opposed him.

After outlining the core tenets of the Conservative Revolution, and comparing it with Nazism, Pető briefly touches upon the life of Jung, focusing on his attempts to unite German conservatives, and other traditionalist opponents of the Weimar Republic into one party during the 1920s. Describing briefly how Jung failed, and Hitler took power, Pető gets to the main subject of the article, the Marburg Speech. According to Pető, this was a botched attempt by Jung and other conservatives to rally right-wing elements against Hitler, and incite their feelings against the regime, by offering an alternative to and a conservative criticism of Nazism.

Jung was disaffected by Nazism since he saw it useful only in destroying the Weimar Republic. However, he considered it unfit to rule Germany. According to Pető, Jung recognized that Hitler’s ‘revolution’ was aiming at constructing a totalitarian and collectivist dictatorship, opposed to the Christian and traditionalist ‘German Revolution’ he envisioned.

In terms of the speech itself, Pető notes that Jung tried to stage his criticism as constructive, and positioned within the system. To this end, he included quotes from Mein Kampf, and lauded Hitler himself. However, Pető outlines, the speech openly attacked certain basic tenets of the Nazi regime. It decried the capture of the free press by the Nazis, as well as the state intervention into the economy. The speech also heavily criticized the ‘vulgar’ antisemitic and racist nature of the system, as well as the fact that

Nazism tried to take the place of Christianity as a kind of ‘political religion’.

To sum, Pető outlines, Jun and Papen’s criticism was focused on the collectivist and totalitarian nature of the regime.

In the last part of the article, Pető asses the speech and Jung’s whole attempt as misplaced and miscalculated in the sense of realpolitik, however courageous in a moral sense. Regarding practical considerations, Pető points out that Jung had underestimated the power and cruelty of the Nazis, and at the same time overestimated the amount of influence conservatives still held in Germany.

Pető reminds that although Jung was among the very first victims of Nazism, his memory has faded away. In his assessment, a Conservative revolutionary hero like Jung would have been considered ‘uncomfortable’ in post-war Germany, since the movement he led had been labelled as a fellow traveller or predecessor of Nazism. However, recent historical research has re-evaluated Jung’s role, which means that he may soon take his rightful place in German historical memory.