The geopolitical term ‘Indo-Pacific’, along with the qualifier ‘Free and Open’, have quickly become widely known in international relations. But what brings together remote places like Madagascar, Taiwan, the Easter Island or Alaska? And what does ‘free’ and ‘open’ exactly mean in relations to this extensive region? A recent book edited and co-authored by two famed scholars provides a good general overview of the Indo-Pacific that has to face the challenge posed by an emerging China, while at the same time the need to maintain the existing rules-based order.

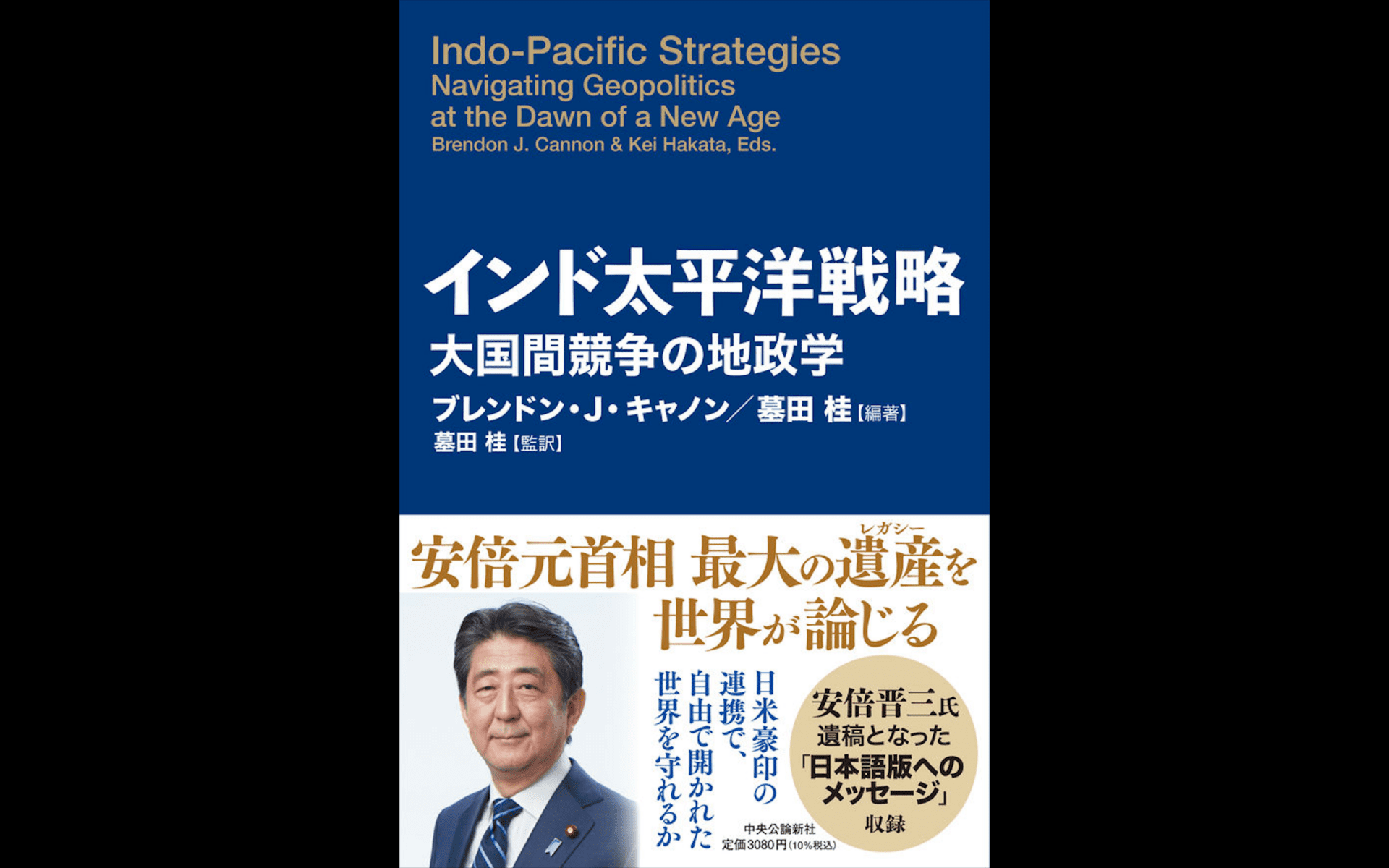

Co-edited by Brendon J. Cannon and Hakata Kei, Indo-Pacific Strategies − Navigating Geopolitics at the Dawn of a New Age was originally released in English in early 2022 by Routledge, and the Japanese edition came out in a more accessible tankobon format in autumn 2022.

The Japanese editor and co-author of some chapters, Hakata Kei may not be unknown to our readers. Hakata is professor of international relations at Seikei University, the alma mater of the late Japanese prime minister, Abe Shinzo. Professor Hakata is a frequent visitor in Europe, including Hungary. He previously lectured and did research in Budapest at the Institute of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Holding a law degree from France and an author of a book on European migration, Hakata is a well-versed scholar, who has a good understanding of the realities and challenges of Europe as well as of the volatile Indo-Pacific region that includes his home country, Japan.

The book focuses on the Indo-Pacific region’s growing prominence, as the world’s major powers gravitate toward this geographical space to expand their influence.

The term ‘Indo-Pacific’ fully replaced the previously used Asia-Pacific, and shows the growing importance of this most dynamic but at the same tumultuous region. The importance of the Indo-Pacific is well reflected in the fact that more and more great and middle powers, such as the US, the European Union, France, Germany, the Netherlands, or Canada have adopted or are working on their Indo-Pacific strategies.

As the book well presents, the Indo-Pacific is not only a geographical region but a strategic concept as well. The stability and the prosperity of the countries in the Indo-Pacific depend on the freedom and the order in the region. The elephant in the room is China. The sheer size of the ‘Middle Kingdom’, the role it plays in the region, its significance in the economies of the countries that surround it, as often the biggest trading partner for everyone, and its growing influence and assertiveness directed at reshaping the existing order have induced the birth of new strategies that help the other players, including Japan, cope with the new realities. The book offers indispensable insights into how the existing rules-based international order is affected and often challenged by China. It also provides up-to-date analyses of COVID–19-related geopolitical trends, and of the strategies of the many Indo-Pacific states from middle powers to small island states.

As its official description says, with dynamic shifts taking place in the globe’s most strategically volatile region, Indo-Pacific Strategies aims at clarifying the geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific, expounded both as a strategic concept and nascent region. The book offers indispensable insights and appropriate remedies to maintain the rules-based international order as threatened by China’s increasingly assertive and bellicose posturing. The book also gives new insights into the roles Eurasia, small island states, the Middle East and Africa, in addition to Australia, India, Japan and the USA play in the Indo-Pacific region, providing a unique mix of comparative studies.

What is the Free and Open Indo-Pacific? — A Japanese perspective

The Free and Open Indo-Pacific, or commonly known as FOIP, officially announced and initiated by then prime minister Abe in 2016, is now the major strategy or ‘vision’ of Japanese foreign policy. In reality it is not only a simple strategy but an ever-changing and adaptive umbrella term incorporating the essential foreign policy strategies of Japan. Nothing describes better the gist of the FOIP than Abe’s own words at the Sixth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD VI) in Nairobi, Kenya, on 27 August 2016, where he first talked about FOIP:

When you cross the seas of Asia and the Indian Ocean and come to Nairobi, you then understand very well that what connects Asia and Africa is the sea lanes. What will give stability and prosperity to the world is none other than the enormous liveliness brought forth through the union of two free and open oceans and two continents. Japan bears the responsibility of fostering the confluence of the Pacific and Indian Oceans and of Asia and Africa into a place that values freedom, the rule of law, and the market economy, free from force or coercion, and making it prosperous. Japan wants to work together with you in Africa in order to make the seas that connect the two continents into peaceful seas that are governed by the rule of law.

To put it simply: the existence, survival, and prosperity of the countries in the region, including Japan, depend on the freedom of navigation in the seas around them and the safety provided by the fact that navigation routes are regulated by international rules and norms not challenged by any of the countries, not least by a big power.

Now, what happens when one player, aiming for global dominance, challenging the existing US-led world order, starts making moves to replace that order with its own and one-sidedly changes existing status quos? The answer that Japan has given to this question lies in the Free and Open Indo-Pacific, which is a fluid term and eludes the easy explanation.

Although FOIP was officially kicked off in 2016, its roots go back to earlier and, unsurprisingly, just as any major strategy and pillar of the current Japanese foreign policy, it was conceived and initiated by the late Abe Shinzo, the most influential and iconic statesman of 21st century Japan. The conceiving of the idea of FOIP dates back to 2006–07, Abe’s first tenure as prime minister, when Aso Taro, later prime minster in 2008–09, and still one of the most powerful politicians in the LDP, was foreign minister. It was called ‘Arc of Freedom and Prosperity’ at the time, but it was the core of the later FOIP.

Abe, as many times during his tenure, was ahead of its time:

he realized that the ever stronger and emerging China represents not only opportunities but also poses a challenge and a threat,

and Japan has to work out the proper response and strategy to cope with the changing strategic situation around its territory. One of the oldest dilemmas of the Japanese foreign policy is how to properly address the challenge from China and adapt to the shift of the power balance in favour of China, bearing in mind its dependence, as China is Japan’s largest trading partner and Japan is the largest foreign investor in the neighbouring giant. A head-on confrontative strategy is not an option: the complexity of the Sino-Japanese relationship requires a subtle, clever, and multi-faceted approach. And a successful strategy also means you need friends and allies. One of the essences of FOIP is to make like-minded countries better engaged in the Indo-Pacific region in order to strengthen the existence of the rules-based international order and better counterbalance any challenges to it.

Abe and FOIP—and its precursors—have showed that handling the complex relations with China, burdened by historic issues and territorial disputes, requires a clever strategy and approach. Abe was able to deliver on this front and managed to normalize relations with China, but at the same time he was never shy to speak out against the growing assertiveness of its big neighbour and insist on the importance of strengthening its country’s defence capabilities. When first elected in 2006, Abe’s first visit as prime minister was to Beijing. After his triumphant return to power in late 2012, Abe visited four times in China while in office, and bilateral relations were moving towards rapprochement. A symbolic event of the improving relations would have been the state visit by Chinese President and CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping in Tokyo in April 2020, but the visit was swept away by the expanding global coronavirus pandemic. It may look paradoxical that relations with China improved under the times of Abe, who was often labelled a ‘hawk’ in the English language media and reached their lowest point and froze between 2009 and 2012, when the Democratic Party of Japan was in power, a party that was openly friendly towards China. This paradox shows perfectly that in foreign policy good intentions alone are not enough: a good strategy and the effective implementation thereof are needed, too.

After the collapse of the DPJ government and the landslide win by Abe and his LDP, the FOIP idea also made its comeback.

Shortly after returning to power, Abe spoke about the ‘Bounty of Open Seas’, a concept that formulated the five pillars of Japan’s foreign policy. The idea later took shape in the form of FOIP, introduced, again, by none other than Abe Shinzo.

The latest important development of FOIP is the revival of the Quad, or the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, between Japan, USA, Australia, and India. The roots of the Quad also go back to 2006–07 and the cooperation was spawned by the visionary Abe himself. The whole story of FOIP and its vitality shows how determining a figure Abe remains in Japan’s foreign policy even in his death.

It is not difficult to see what brings together the above mentioned four countries that are as diverse as they can be: the challenge posed by China. Although it is never openly mentioned that the Quad is a grouping aiming to counterbalance the influence by China, in fact it is. Though often labelled as the ‘Indo-Pacific NATO’ and viewed as a military alliance by Beijing, Quad is neither an alliance nor a military alignment either, and it was never meant to be such. Quad is almost as hard to grasp as FOIP itself, and for those who are more interested in what the Quad is and isn’t, I recommend reading a very good summary by Stephen Nagy of the International Christian University.

There are many ways to look at and understand FOIP which will surely remain the key foundation of Japan’s foreign policy in the coming years, with more and deeper involvement of European partners. The significance of the Indo-Pacific region therefore reaches over its physical perimeters. In fact, another way of looking at FOIP is that it is an alternative to China’s ‘Belt and Road’ strategy: a sustainable growth model based on international rules and norms.

An Unplanned Memory to the Great Abe Shinzo

The best recommendation for the book comes from Abe Shinzo, quoted many times here, whom I would call the ‘Father of FOIP’:

‘I think this book is the timeliest attempt to bring together the wisdom of eleven people to present a multifaceted view of the FOIP [Free and Open Indo-Pacific].’

The official book launch event of the Japanese edition was held in October at the Kinokuniya Hall in Tokyo, co-organized by the Seikei Alumni Association. But the event, that was supposed to be opened by Abe himself, couldn’t have been festive or celebratory. Every participant felt the gaping absence of the most important person of FOIP, Abe Shinzo, who was murdered in July 2022. Though not originally planned, the book commemorates the great statesman.

I hope this short review will increase the appetite for learning more about this dynamic and volatile region, in which this book can be a great help. This unique publication is not just a very valuable reference book for students, but also an essential read for scholars, policymakers or strategists, and in fact for anyone interested in the Indo-Pacific.