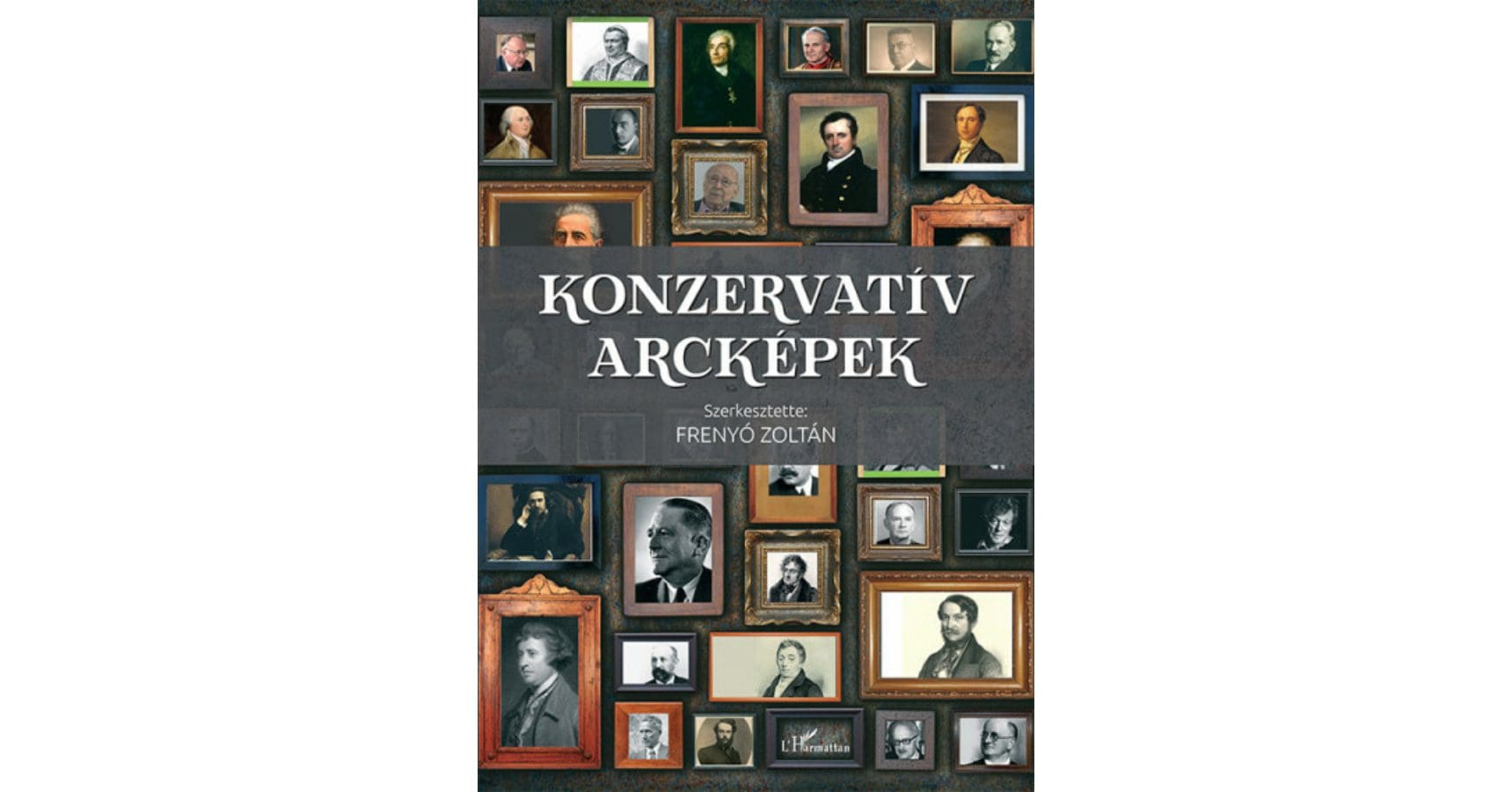

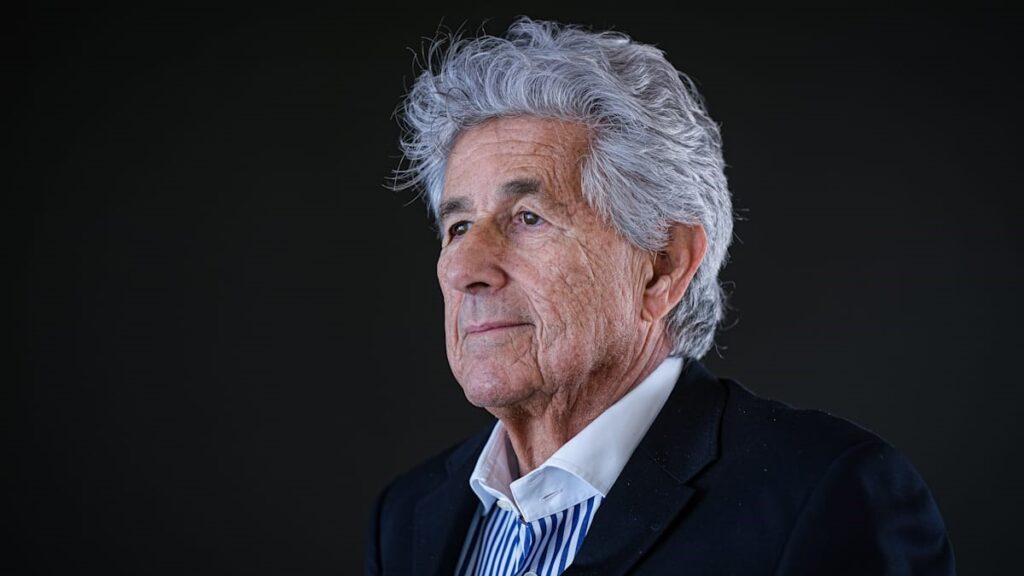

Zoltán Frenyó is a former senior research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. He received his degrees in history and philosophy from Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest and earned his PhD in Philosophy in 1997 an in History in 2002. His research interests include philosophy of religion, early Christian thought, and twentieth-century Christian philosophy, including the history of Hungarian ideas. Many of the thinkers included in the volume have strong Christian ties, from Ottokár Prohászka (1858–1927) through László Ravasz (1882–1975) to Pope John Paul II (1978–2005). In terms of distribution, two-thirds are foreign and one-third is Hungarian, while the universals are all European or American, and thus all come from the Euro-Atlantic civilization. The volume should therefore be of interest to readers from across the ocean and beyond.

He rejects the conservative classification of American neo-conservatives as being logically liberal in basis, conservative in name only

At the beginning of the volume, Frenyó attempts to define conservatism, mostly in the light of Anglo-Saxon authors, but he also includes the problem of the German conservative revolution, pointing out that some currents of conservatism have distinctly different characteristics from that of the Anglo-Saxon trends that are generally known. The volume also includes several German thinkers who can be classified as conservative revolutionaries (Ernst Jünger (1895–1998), Hans Freyer (1887–1969), Edgar Julius Jung (1894–1934), in order for the Hungarian readers to get to know these people, since not many of their works have been translated in Hungary. The editor’s basic thesis is the irreconcilable opposition between conservative and liberal ideas, in contrast to the Western European trend that conservatism can be liberal. He rejects the conservative classification of American neo-conservatives as being logically liberal in basis, conservative in name only. But it is not only neo-conservatives that one would look in vain for in the volume, as some other thinkers who are considered conservative by popular opinion, such as the Hungarian Gyula Szekfű (1883–1955), are not included either, since, according to Frenyó, Szekfű always sought to legitimize a political system (usually the existing one) and changed his position accordingly in his works. According to the editor, the final organizing principle was the idea of striving for normality, that is to include the persons to be presented in the volume along the lines of political and value conservatism.

The individuals included on the basis of the above criterion are often not mainstream thinkers. Some of them have been “forgotten”, as a result of the change in values in the 1960s, such as the historian-sociologist Christopher Dawson (1889–1970), who had a major impact in the first half of the twentieth century, or T.S. Eliot (1888–1965), whose literary work could not be ignored, but whose role in political thought was neglected. But the aforementioned German conservative revolutionaries, or the French radical conservatives like Charles Maurras (1868–1952) or François-René de La Tour du Pin (1834–1924) are not part of the mainstream either. It is for this reason that the publication of this volume is welcome, as the editor not only briefly describe lesser-known or misrepresented figures, but also their works and the literature on them. This feature makes the volume suitable for students in higher education to choose a research topic, while the language of the studies makes them easily accessible to readers with non-academic interest, as well. The only minor flaw of the work is that it presents the leader of the Hungarian conservatism during the reform era (1825-1848) Count Aurél Dessewffy (1808–1842) as a reformer of feudalism together with the conservative camp, whereas Aurél’s brother Emil Dessewffy (1814–1866) was talking about the necessary end of feudalism, and his work was mainly concerned with trade, monetary and infrastructural issues. In his articles Aurél Dessewffy himself did not argue about the necessity of self emancipation, but about how to achieve it.

Among the 74 conservative thinkers included in the volume, anyone can find a movement or person that interests him or her, whether French counter-revolutionaries, Russian Slavophiles, German Christian Socialists, Italian Christian Democrats or Hungarian noble conservatives. The “protagonists”of the collection are the natives of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the two centuries that have most influenced our present. Thus, the views, debates and aspirations of the thinkers in this volume are also relevant from an ideological-historical point of view. Although by the end of the twentieth century, the view had emerged that liberal democracy had won a definitive victory, the ideas of the characters in this volume demonstrate that there are always alternatives and that history is full of them.