February marked the second anniversary of the coup d’état in Myanmar, when the Burmese military retook full political power and put an end to a short-lived and fragile period of democratic rule. More than two years later, the country’s longstanding civil war has become even bloodier, but the world seems to have moved on, and the focus of the free world has shifted to the war in Ukraine and tensions in the Taiwan Strait. As a consequence, nobody seems to care much about Myanmar anymore, much like how many don’t care about Afghanistan, its internal implosion, and its subsequent decay. The US, the EU and Japan, who enthusiastically embraced the ‘Burmese Spring’ ten years ago, are now left with the dilemma of whether to remain engaged with the junta tainting their own credibility, or move out and impose sanctions on the army and the country, pushing them into the arms of China and Russia.

The Burmese Spring

After half a century of brutal military rule, Myanmar’s democratic re-opening, often referred to as the ‘Burmese Spring’ came swiftly and unexpectedly. Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate and democracy activist, a revered symbol of opposition and the struggle for freedom, was released from detention. At the 2012 by-election, her National League for Democracy won most of the seats up for grabs, which was followed by a landslide win in the 2015 elections.

At that point, the attention of the world turned to Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, a large country in Southeast Asia, whose strategic importance had grown thanks to its untapped natural gas reserves and also because as a now democratic country, Myanmar became another potential ally to offset China’s influence in the region. World leaders flocked to Yangon (called Rangoon in colonial times), the capital of the country. Then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton met with Suu Kyi, ‘Burma’s Iron Aunty’ in 2011 and 2012. Foreign investors came, and while the military still exercised huge influence on political life and remained in control of large swathes of the economy, the poor country embattled under brutal military rule and continuous violence between the military and different ethnic groups, stepped onto the path of economic recovery.

A Short-Lived Democracy in the Post-British Era

Myanmar, a former British colony, regained independence in 1948. A key person of the independence movement, and the founder of modern-day Myanmar was the father of Aung San Suu Kyi, Aung San (The author’s note: There are no family names in Burmese, Aung San Suu Kyi’s name is the combination of the names of her parents), who is called the ‘Father of the Nation’ or the ‘Father of Independence’. Aung San, a shrewd politician and diplomat working for both Imperial Japan and Britain as his and his nation’s interest required, negotiated the details of independence from Britain, settled in the Aung San-Attlee agreement, in 1947.

Aung San couldn’t live to see his country’s liberation: soon after he and his party won the first general election in 1947, he and most of the members of his newly established cabinet were assassinated, shortly before the country became independent. This was the circumstance of the birth of the new country that set the tone for future politics.

Although Aung San was murdered by his political adversaries, there are theories that suggest that Britain was involved in the assassination.

Under British colonial rule, before independence, Burma was one of the wealthiest countries in the region. The former capital, Rangoon, was a thriving, bustling, cosmopolitan city with a vibrant life and economy. All this came to a sudden end when in 1962 a group of army officers led by the ruthless General Ne Win seized power and put the country on the path of the so-called ‘Burmese Way to Socialism’. We in Hungary know, many of us from first-hand experience, the success rate of socialism. It wasn’t much different in Burma either. Foreign-owned private businesses got nationalised, there was a mass exodus of foreigners, mostly Indians, who were often the target of hate campaigns throughout history in many parts of the world in Asia and Africa. The country became impoverished and isolated, and to make matter worse, sanctions on the regime introduced continually from the mid-1990s onwards further deepened economic woes.

The Years of Aung San Suu Kyi

Aung San Suu Kyi, who returned home in 1988 got immediately involved in politics and was a key figure of the peaceful democratic movement, which later became known as the 8888 Uprising. Suu Kyi founded the National League for Democracy (NLD), which is still the main party of the pro-democracy camp. She was quickly arrested by the military junta unwilling to cede power. She was offered freedom if she leaves the country, but she chose to stay and became the symbol of the freedom movement. In 1991 she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Suu Kyi, who spent 15 of the 21 years since her return to Myanmar under house arrest was released in late 2010, after another shady and rigged election held by the junta. After her release, her popularity became visible, with large crowds accompanying her everywhere. Foreign leaders like Hillary Clinton and William Hague, the foreign secretary of the UK, still the largest donor of the country, rushed to Yangon. Suu Kyi went on a European tour, and negotiations started between the junta and her and her party, NLD. In 2012, Aung took her seat in parliament.

Later, in 2012, President Obama welcomed the superstar of Burmese democracy in the White House.

Embracing the young democracy and increasing US influence in Myanmar fit well into Obama’s pivot to Asia foreign policy strategy.

In the 2015 elections Aung and her NLD won a sweeping victory, and she became the country’s de facto prime minister. Because of constitutional constraints, as Suu Kyi was married to a foreign citizen, she formally couldn’t become president; but it was more like a good excuse for the military not give her a proper title. But Suu Kyi, a politician and activist hardened in battle, made sure she would hold the real power in any NLD-led government.

The country broke out of isolation and foreign investment poured in. The Western world stepped in the same river again and believed that democratisation is a one-way street and Myanmar is on the road to full democratisation.

And yet, there were many signs that things were not as simple as that. The military still wielded significant power and the persecution of the Muslim Rohingya minority, described as one of the biggest ethnic cleansings and refugee crises since the Second World War, tainted Suu Kyi’s image.

The Coup Everybody and Nobody Expected

Myanmar held a general election in November 2020, where Suu Kyi and the NLD won a landslide victory, giving her enormous political power and credibility. The military, which never actually retreated from political life and remained a key player in domestic politics, never planned this. The release of Suu Kyi was a gesture to the outside world and a tool to release the tension, but the generals realised they not only released a symbolic and popular politician, but also a genie from a bottle. The truth is, the military junta never planned for Aung San Suu Kyi to have significant power, but to play a symbolic role, a fig leaf of democracy while they retained control over the country. Her landslide win was dangerous for the Tatmadaw, and they moved to stop it.

Retrospectively, one can say it had been in the making. But how unexpected the coup was is plainly demonstrated by an epic video on YouTube, in which a fitness trainer is holding a public dance workout session, totally oblivious to the motorcades of military vehicles roaring in the background, later capturing strategic buildings and institutions. Tom Andrews, the United Nations special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar spent his time assuring people that a coup was not actually going to happen during the days leading up to the coup. He admitted to Foreign Policy Magazine that he argued that the military won’t be likely to stage a coup because they had just too much to lose. Interesting how history can repeat itself: we heard the same argument many times running up to Putin’s military campaign against Ukraine.

The generals, with the new leader of the country, Min Aung Hlaing, thought that things were just back to normal: nothing to see here. The official reason for the military power grab was that the elections were rigged and there were major frauds, which is an obvious charade. The military didn’t take into account the fact that a decade had passed since the Burmese spring, and millions of young Burmese experienced the liberating climate of, albeit limited, political freedom and the economic freedom and prosperity that followed. What the military junta achieved were large pro-democracy protests, and widespread violence throughout the country to a scale unseen before (the history of modern Myanmar is riddled with armed violence, mostly between the central power and ethnic minorities.)

One could rightfully ask why Myanmar is special when a military coup is more or less a common phenomenon in neighbouring countries such as Thailand and democracy is generally in short supply in the broader neighbourhood. Take for example Vietnam, a country embraced and approached by many, including the USA and Japan, which is a communist country, where the Vietnamese Communist Party is busy centralising power and although there are elections, voters can only choose from candidates approved by Vietnamese Fatherland Front—an ersatz electoral process very familiar to any Hungarian who was an adult before 1990. Laos is also a communist country with a one-party system; Cambodian elections are sham, and everyone knows that the next leader of the country will be the son of the current prime minister, Hun Sen.

A Brutal Dictatorship Cozying Up to Russia and China

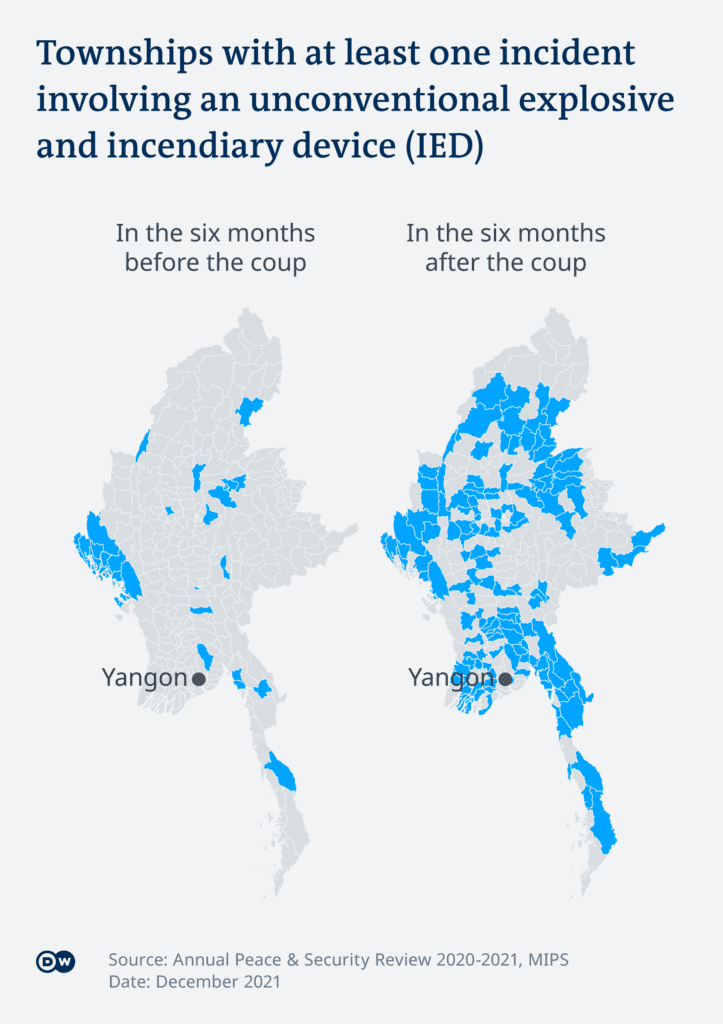

So why the fuss about just another military coup in a region where democracy by Western norms is hard to find? The answer lies in the level of brutality. The map below gives a glimpse of how different the level of violence in the country is compared to the time before the coup.

Since the coup more than three thousand people, including civilians have been killed by military crackdowns,

and more than fifteen thousand have been detained, and more than 1.5 million people remain displaced across the country due to insecurity and violence. A recent leaked memo from the Tatmadaw admits that resistance to the military rule is growing beyond control, which has prompted he military government to allow civilians it deems ‘loyal’ to carry guns to help in its crackdown against armed resistance.

The other aspect is the challenge of Chinese and Russian influence. As the world returns to a bipolar system with the USA, NATO, G7 and their partners on one side, and the new axis of evil with Russia and China on the other, it is not an easy choice to write off investments and efforts of a decade and let the vacuum be filled by China or Russia, two big powers not having second thoughts about internal problems or democratic deficit. The new military leader, Min Aung Hlaing, is a big admirer of autocratic strongmen and dictators, including Vladimir Putin. During his trip to Moscow in September, he praised the bloody Russian dictator for ensuring global stability and making Russia number one in the world. Though the Tatmadaw has always looked on China with suspicion and managed to decrease military dependence on China, the Burmese army might not have second thoughts about turning to Beijing for help if further sanctions should make it necessary. Beijing, which cynically described the coup as a ‘cabinet reshuffle’, will be definitely happy to help to push US and Western influence out of the region and of its immediate neighbourhood.

Furthermore, there is always a humanitarian aspect to the bloody conflict, which is technically the longest running civil war in the world. If the so-called West or the democratic world moves further to isolate Myanmar and punish it with sanctions, it would trigger an even worse humanitarian crisis and make life more miserable for the masses who have been protesting at and opposing the military dictators during the past two years, risking their freedom and lives.

The military junta has extended the nationwide state of emergency by another six months, drawing outrage from the international community. Myanmar is supposed to hold a general election within six months, but the fact is that due to the widespread conflict spanning vast areas of the country, the central military government is not in full control of the country and obviously incapable of holding a normal election. Moreover, even if the junta does manage to hold an election, it will be a rigged one, a simple fig leaf to cover the brutal nature of their rule.

The West Is Focused on Ukraine

There is a high probability that the military junta will remain in place, while the country slides into an even bloodier civil war, as the attention of the international community is wearing thin and the political will to intervene has waned. The last two years of Myanmar is another good example of the limits of the ASEAN to solve problems, or to become an effective mediator. In neighbouring Thailand, the regional middle power, control of the country still rests with General Prayut Chan-o-cha since his successful coup in 2014, and Thailand has traditional friendly ties with Myanmar. Just a month ago, in late January, Thailand’s chief of defence services paid an official visit to Myanmar and met with General Min Aung Hlaing – not a sign that ASEAN were planning any pressure on Myanmar to bring peace closer in the civil war ridden country.

The Western powers, the USA, the UK or the EU are obviously focusing on Ukraine, a bloody war in Europe, fearing that the aggressor, Russia will not stop there and will launch an attack against other countries, escalating its war. It doesn’t help the case for Myanmar that Ukraine is a sovereign country invaded by its big neighbour, while seeing from afar, the present situation in Myanmar looks like just another episode in the country’s many decades of internal conflicts.

Japan, holding the G7 presidency this year, has historically friendly ties with Myanmar,

and has taken a traditionally more favourable stance towards the country compared to Western powers even before the Burmese Spring. After 2012, Japanese investments poured into Myanmar and Japan played a significant part in helping the country from institution-building to modernising the military. While it is therefore understandable that Japan remained hesitant to sever ties with the Yangon regime, it is very telling that it took four months for the Japanese lower house to condemn the military takeover.

The end of the Tatmadaw is not in sight. On the contrary, despite the escalating civil war, the military is still stronger, richer, better equipped and more capable than the rebel fighters. As there seems to be no real appetite from outside powers to get involved, for example by arming pro-democracy forces, the international community should do the minimum in the long term: reject the result of the charade of an election held by the junta. There is no way that any free and fair election could be held when it is a crime to criticise the junta, which is detaining, torturing and killing the opposition.

The situation of Myanmar and the chances of the pro-democracy forces are a lot more hopeless than they were before 2010, as there is no such powerful and symbolic ally as Aung San Suu Kyi. Although there are calls for her immediate release, there was also a petition a few years ago to revoke her Nobel peace prize. Aung San Suu Kyi’s image got seriously tainted as Myanmar’s elected leader when she oversaw the atrocities against, including ethnic cleansing and persecution of the Rohingya minority by the army in the late 2010s, and today, she is more or less isolated internationally. She is no longer the human rights icon she once was, thus she can no longer be the catalyst for human rights pressure from abroad. It is not clear if Aung San Suu Kyi is still the solution, or more of a burden, or just an icon of the past.

There is no visible strategy as to how to handle the tragic Myanmar situation by the so-called West. The most likely scenario is that the United States and its allies will start the usual cycle again: sanctions and then the easing of sanctions in return for concessions by the junta. First, it is not sure the old playbook will work again. Second, as already noted above, there is a chance that sanctions would just increase the burden on the Burmese population and would do less harm to the military junta itself. Third, the Tatmadaw couldn’t care less about the suffering of the people, especially not when it is them who have been committing violence against their own populace.

What we can learn from recent history of the country is that as a rule, the Tatmadaw make concessions when they want something in return: the easing of sanctions, international recognition, or something to that effect. The military junta will only yield to outside pressure if they have no other choice. As long as they can rely on Moscow or Beijing, two major powers happy to counter US influence anywhere in the world, there is little chance in the short term to have the country turn back from this road to hell.