To the young voter in Hungary today, the domestic politics of the 1990s is not a personal experience, but history. This period is a childhood memory for the millennials; while the older generation can already draw up the balance sheet of the third of a century that has passed since the fall of communism in 1989–1990.

One of the vividly preserved childhood memories of the author of these lines is, at age eight, watching on television an elderly man standing on the balcony of the Parliament in Budapest in October 1989, who proclaims the Republic of Hungary after the fall of the Communist dictatorship. ‘What is a republic?’, I asked my parents, who seemed to be deeply moved, and I may have even seen some tearful eyes, too.

The 1990s brought Hungary a real rollercoaster in terms of society, economy, and politics, just like in any other post-communist nation. Instead of the rose-coloured utopia of rapid development and immediate prosperity, the country witnessed structural crises and the impoverishment of large layers of society, while some rose fast. Hungarian society, which had gone through a lot in the 20th century already, was simultaneously hoping for things to take a slow turn for the better, while also doubting the plausibility of realising the grand promises of the new system.

The First Conservative, ‘Kamikaze’ Government

Hungary’s first freely elected government was the cabinet led by Prime Minister József Antall. It included the right-wing people’s party MDF, the Smallholders Party, which could boast a long tradition, and would most likely be called ‘populist’ today, as well as the Christian Democrats, who had a revival after the fall of communism. PM Antall, a well-educated, well-informed scholar coming from an upper-middle-class family, was a devout Christian and democrat. He had to face the challenge of his life: entering the politics of Hungary after the regime change, he had to step up to be the head of government for a country facing a complex crisis.

Although he was heavily criticised by his opponents, and many kinds of social tensions arose in those years, Antall’s integrity was never in question.

However, during his time in office, which was described by some as ‘kamikaze’ governing, he suffered from cancer and passed away in 1993.

After the 1994 election, the post-communists got back into power under the banner of the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP). While they did get a clear majority on their own, they formed a coalition with the party of the urban liberals, the Free Democrats’ Alliance (SZDSZ). Thus, the two parties together secured a two-thirds majority for their term. The right-wing conservative parties of Hungary had fallen apart, and their supporting base had to sadly accept the fact that the ‘communists’, as the left was colloquially still called at the time, got back in power after just four years through a democratic process.

The Gyula Horn-led liberal–socialist government showed the face of a technocratic administration to the outside world. However, domestically, the administration was privatising public property at a fast pace, mostly selling it off to foreign investors to make up for the loss in revenue due to the economic downturn. They sold large state-owned enterprises, and even the strategically crucial utility service providers, such as the public water and gas companies.

On top of all that, due to the acute economic crisis, then-finance minister Lajos Bokros implemented harsh neoliberal reforms in 1995. Although this did improve the fiscal balance, it also pushed the already weak middle class closer to the poverty line, while the untrained, unemployed strata of society survived on minimal welfare, without the need to find employment. In the meantime, on the surface, the ‘culture war’ continued between the liberal intelligentsia in power and their conservative counterpart out of power, on a less-than-level playing field.

The 1998 parliamentary elections took place in this milieu, under the two-round electoral system in place at the time. Truth is, the support for the left-wing liberals was not as small going into the election as many expected. On the other hand, the right-wing parties were occupied with infighting.

Viktor Orbán’s Path to the Right

After the 1994 loss, complex political manoeuvring started on the right, trying to determine who the leader of the camp would be after the death of József Antall and the weakening of MDF. This is where the opportunity arose for Fidesz, a party which once started as appealing to liberal intellectuals, to open towards the conservative right. After many years of organisation,

Viktor Orbán emerged as the new leader of the Hungarian right.

However, in order for that to happen, many large-scale events had to take place first, independently of Fidesz’s actions. First, Fidesz, which started as an anti-regime movement during the socialist era, had to unequivocally disassociate itself from the post-communist powers and from entering any sort of alliance or coalition with them. This opposition had always been stronger between Fidesz and the left-wing parties than the one between the liberal-rooted party and the conservative base.

In the early 1990s, the larger liberal party at the time, SZDSZ, tried to create a liberal pole along with Fidesz, in opposition to the right and the post-communist socialists. However, in a move that has had an effect on Hungarian politics to this day, SZDSZ teamed up with MSZP, and the two made various efforts to ‘grind down’ Fidesz.

The Fidesz presidency, and especially Viktor Orbán, guided by a long-term political vision, were able to counteract these efforts. Despite all the luring and threats from the liberal intelligentsia, Fidesz kept itself away from the coalition of the Socialists and the liberals. This resolute stance had a significant impact on the future history and principles of the party.

While in the 1994 elections, Fidesz found itself in a sort of political and ideological ‘vacuum’ and thus performed badly, the party, led by Orbán, had since turned towards the right, and was seeking to offer a viable alternative to oppose the post-communists.

After multiple years of rebuilding the organisation, forming new political alliances, and inner conflicts, the conservative side, which ended up becoming attractive for older intellectuals as a result of all of this, eventually accepted the leadership of a young Viktor Orbán. By early 1998, the Orbán-led Fidesz, the Socialists, and the Smallholders’ Party competing with Fidesz on the right, had a real chance for victory.

1998: The Year of Generational Shift in Politics

The first round, held on 10 May 1998, was won by the Socialists, to the surprise of many. MSZP got 33 per cent of the popular vote, Fidesz received 29 per cent, while the Smallholders got 13 per cent. SZDSZ, which had weakened along with MSZP, shrank into a seven-percent party. The far-right nationalist MIÉP also passed the parliamentary threshold with five per cent .

Despite the left-wing victory, however,

the results clearly showed that with a reasonable agreement between Fidesz and the Smallholders Party, they could obtain the majority after the second round.

The two parties managed to agree on withdrawing certain candidates in favour of each other, thus, typically, one Socialist and one joint right-wing candidate faced each other in the second round—and the right-wing coalition won.

In order for that to happen, however, a televised debate, memorable to many, had to take place between the then-35-year-old Viktor Orbán and incumbent PM Gyula Horn. Horn was a generation older than Orbán and started his political career in Stalinist Hungary, then went on to achieve international fame as a technocrat in the 1980s and 90s.

The famous TV debate ended up becoming a clash of generations, worldviews, characters, and ideologies—which only helped build Viktor Orbán’s reputation as the accepted leader of the Hungarian right, and as the next Prime Minister of Hungary. That is because, in this open and honest debate, Orbán could present an alternative to the post-communist, technocratic view of the world. Although he did not espouse the same conservative values as he does today, this debate was a true milestone leading him to a moderate, civic right. This was later appreciated by the voters.

After the 1998 election, a three-member coalition consisting of Fidesz, the Smallholders, and MDF (which survived as a small party) was established. The Hungarian conservatives side managed to form a government again.

The famous TV debate ended up becoming a clash of generations, worldviews, characters, and ideologies—which only helped build Viktor Orbán’s reputation as the accepted leader of the Hungarian right, and as the next Prime Minister of Hungary. That is because, in this open and honest debate, Orbán could present an alternative to the post-communist, technocratic view of the world. Although he did not espouse the same conservative values as he does today, this debate was a true milestone leading him to a moderate, civic right. This was later appreciated by the voters.

After the 1998 election, a three-member coalition consisting of Fidesz, the Smallholders, and MDF (which survived as a small party) was established. The Hungarian conservatives side managed to form a government again.

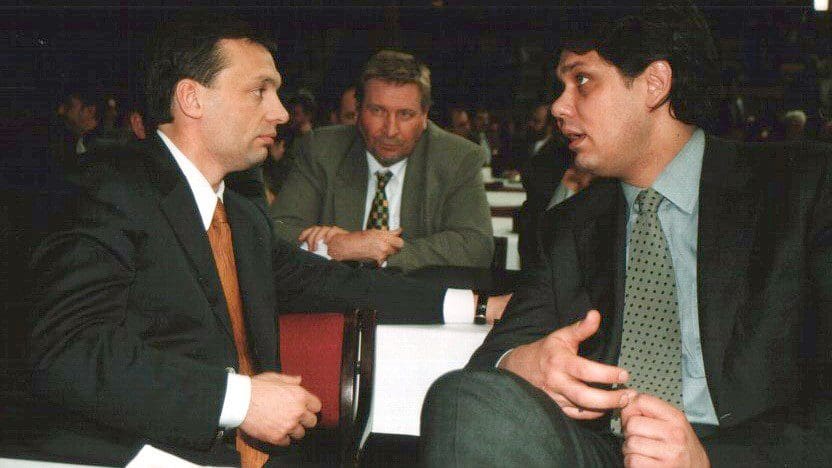

PM Orbán talks to the press following his meeting with Bill Clinton on 7 October 1998. PHOTO: Alamy

Hungary’s accession to NATO happened during the first Orbán administration. Initially, many believed that joining the EU would soon follow: originally, the quick and joint accession of Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland was planned. However, ultimately, a decision was made at the international level that these three countries would join the Union, along with seven other countries, only in 2004.

Thus,

while it was Viktor Orbán who took Hungary to NATO, he only got to lay the groundwork for EU accession.

During his time in office between 1998 and 2002, Orbán put Hungary on a fast track of development, and was also able to decrease the national debt that had been amassing at an alarming rate since the last years of communism. The curbing of the crime wave that had started in the early 1990s brought more peaceful times. Society could prosper once again, and could turn their focus to the future again by the turn of the millennium. Hungary became a part of Western alliances, while the country also celebrated its 1,000th anniversary in 2000. Although many scandals erupted in the ranks of the smaller coalition partner, the Smallholders, and the party completely collapsed by 2002, Fidesz only gained from that, and became a people’s party enjoying the support of nearly half the country.

Many on the right were hoping, or outright took it for granted, that the conservative administration could continue its work after the 2002 election. However, that didn’t happen. Instead, MSZP and SZDSZ managed to squeeze out a narrow victory. Viktor Orbán’s party was forced to take an opposition role again.

For Fidesz and the right-wing base, this election loss was another breaking point. However, it also inspired Fidesz to engage in further political innovation, and develop new strategies in organisation and communication—which later became the basis for the new era of governing starting in 2010. But that is a story for another day.