An Electoral Guide to and a Statistical Analysis of the 2022 Hungarian Elections

On 3 April, Hungary held its ninth democratic general elections since the fall of communism. Despite previous hopes from the international progressive left and a mostly united opposition ranging from ex-communist to ex-far right parties, the ruling conservative coalition won a stunning and historic victory. Fidesz and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán secured more votes than any party since the fall of communism both in percentage terms and in the number of votes cast, and thus secured a fourth consecutive term, retaining their two-thirds supermajority in Parliament as well. How did this historic victory happen, and what are the underlying social and demographic trends? In this article I will look at some of the available statistics and try to answer these questions.

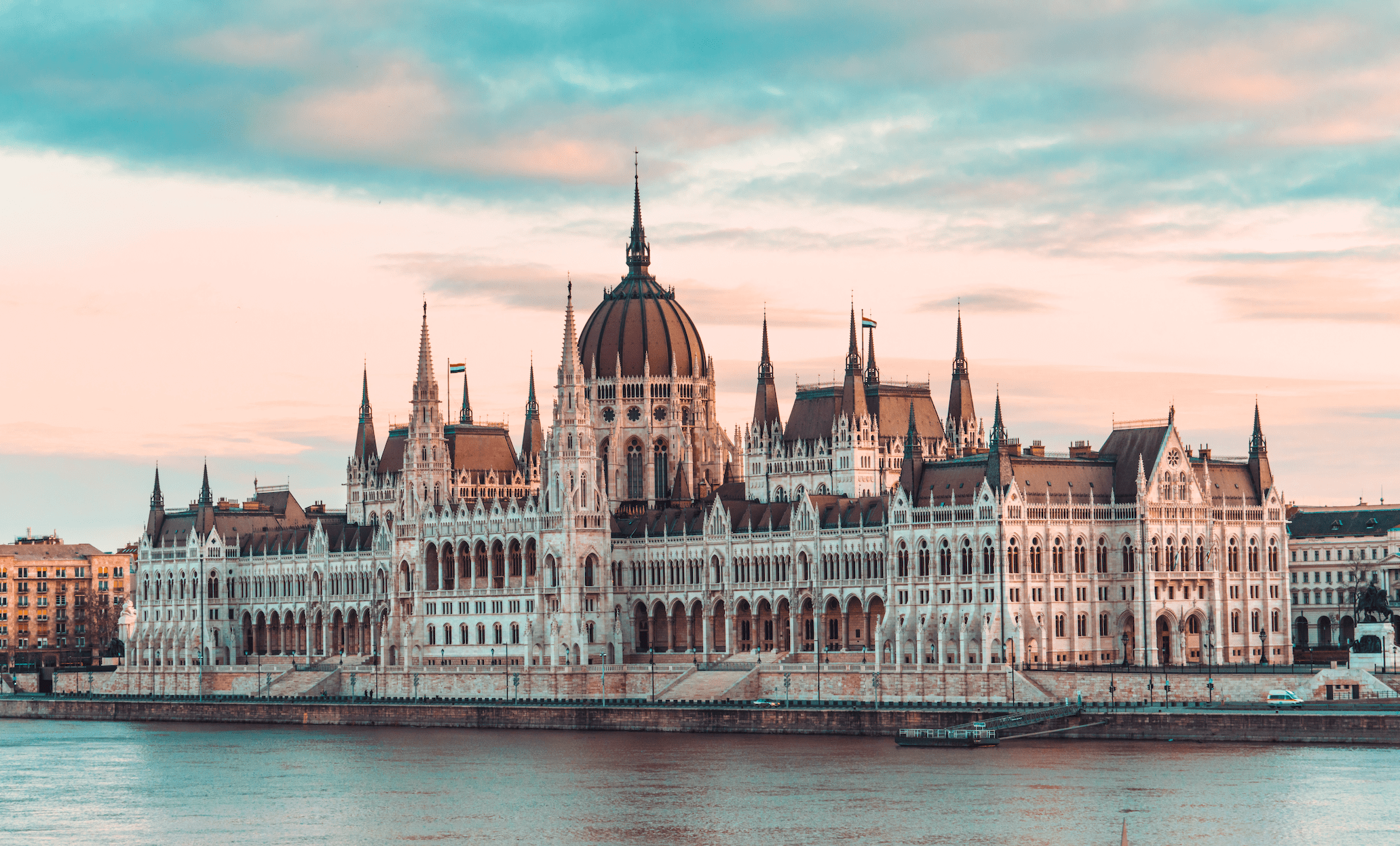

Hungary’s Electoral System

Hungary has a so-called mixed electoral system in which the 199 members of parliament are elected by two main methods.1 A slight majority of members (106 seats) are elected in single-member constituencies by a first-past-the-post vote similar to the United Kingdom or the system used in the US congressional elections. Here the candidate who receives the highest number of valid votes cast in a constituency, irrespective of the number of people present, is elected to that seat. The remaining 93 members are elected from party lists from a single nationwide constituency by proportional representation, via a partially compensatory system using the so-called d’Hondt method. There is also an electoral threshold for the party lists which is set at 5 per cent. This is raised to 10 per cent for a coalition of two parties and to 15 per cent for a coalition of three or more parties.

Since 2014, each of the thirteen recognized Hungarian ethnic minorities2 can win one of the 93 party list seats if they register a specific minority list and reach a lowered quota3 of the total of party list votes. In practice only the German and Romani minorities are numerous enough to possibly elect a member of parliament. The German minority has successfully elected a member of parliament in the previous elections in 2018, and in the current one as well. The other minorities, if they are not able to reach the lowered quota, also have the opportunity to send a minority spokesperson to Parliament, who has the right to speak and address the Parliament but not the right to vote.

In 2011 an amendment made it possible for ethnic Hungarians living abroad to vote in the Hungarian elections

The question of the citizenship and voting rights of the 2 to 2.5 million Hungarians living in the neighbouring countries has been a divisive topic since the fall of communism. Generally, the left has been against giving citizenship and voting rights to them, while the right has been more in favour of doing so. In 2010 the current government made it significantly easier for ethnic Hungarians living abroad to obtain Hungarian citizenship, and then in 2011 an amendment made it possible for them to vote in the Hungarian elections (only on party lists) as well. Since 2010 more than 1.1 million4 ethnic Hungarians have received citizenship, but usually only between 100,000 and 300,000 of them vote. Therefore, as matters stand there are essentially two ways a Hungarian living abroad can vote in the Hungarian elections. Those Hungarians who, though living abroad, still have a Hungarian official address (these are usually Hungarians working or studying in Western Europe) can vote both for one single-mandate constituency candidate and one party list at a representation abroad. Hungarians who have no address in the country (mostly Hungarians living in the neighbouring countries) can vote by post, but only for a party list.

Because the overwhelming majority of postal votes from the neighbouring countries usually go to Fidesz, the opposition has regularly criticized these voting rights, and also the practice of mail-in ballots. Still, if we look at the electoral statistics it is clear that these votes hardly influence the outcome of the elections. Firstly because these voters only have the opportunity to vote for the party list, and also because their participation rate is significantly lower than the general population; in 2014 these votes only influenced the election of one, in 2018 zero and in 2022 two members of parliament.5

The Road to the Elections and to a United Opposition

After the abysmal results of the 2010 elections, where the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) received less than half of the votes they received in the previous 2006 elections, the Hungarian left became increasingly fragmented. This fragmentation reached its peak during the 2018 elections when the country had at least seven different major parties on the left.6 After the disappointing results of that election, in which the formerly far-right party Jobbik became the second strongest party in parliament and received almost twice as many votes as the third largest party, the opposition parties of the left faced increased pressure from their voters to change their election strategy.

Also, despite becoming the leader of the opposition, the leadership of Jobbik was also disappointed by the results, as they had hardly managed to increase their voter base. It also showed the limits of the so-called ‘cuteness’ campaign followed by the party leadership, which sought to transform the far-right party into a respectable centre-right force. The leader of the party, Gábor Vona, taking the blame for the disappointing results, resigned, and the more extreme elements of the party planned to split from it (which slowly happened in the coming years). Therefore, the leadership of the opposition parties faced increased pressure for change, which was also heavily influenced by the fact that the major opposition parties, if taken together, won almost the same number of votes as Fidesz. This led certain left-wing pundits and opposition think tanks to advocate for a united opposition.7

The argument was that by running together, especially in the 106 single-member constituencies, they would have a better chance of defeating the Fidesz candidates, especially in the capital and in the bigger cities. Of course, this strategy was heavily reliant on the assumption that all the votes cast together for the opposition parties would automatically transfer to a united opposition as well. Thus, a far right voter would happily vote for a liberal or socialist candidate and vice versa.

This strategy was eventually partly tested in the 2019 municipal and local elections, with some success. During the elections, five left-wing parties ran with a joint list and in some places, especially in the countryside, even Jobbik, local parties, or independent candidates joined them. The opposition managed to win the mayoral race of the capital city Budapest and secured a majority in its general assembly as well. They also managed to win 10 out of the 23 major cities8 in the countryside. This was a significant improvement for the opposition, as during the previous local elections Fidesz had won a majority in Budapest and also won 20 out of the 23 major cities.

Building on this partial success, the main opposition parties started the negotiation process for running jointly at the 2022 general elections as well. At first, in August 2020, the main parties agreed that they would field joint candidates in all the single-member constituencies. Later that year they also agreed that they would have a common candidate for the role of prime minister, while in December, to solidify they electoral alliance, they finally agreed to not only field joint candidates but to also run on a joint list. The alliance was ultimately named United for Hungary (Egységben Magyarországért) and was made up of the following quite diverse parties and movements:

The main opposition parties started the negotiation process for running jointly at the 2022 general elections

· Democratic Coalition (DK)—a splinter party established by the former socialist prime minister of Hungary, Ferenc Gyurcsány. The party is strongly pro-European, even supporting the idea of the United States of Europe, and both socially and economically liberal.

· Jobbik—a formerly far-right, eurosceptic party, which tried to transform itself into a modern conservative people’s party. The party currently defines itself as a Christian, conservative, centre-right, socially sensitive people’s party.

· Politics Can Be Different (LMP)—the first green party in Hungary, advocating liberal, green policies.

· Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP)—the successor of the former communist ruling party of Hungary. It currently identifies itself as a centre-left, social-democratic and pro-European party.

· Momentum (MM)—a young, progressive party which came to national prominence as a political association in January 2017, after organizing a petition regarding the Budapest bid for the 2024 Summer Olympics, calling for a public referendum on the matter. It is generally a pro-European, pro-globalization, socially progressive party which supports gay marriage and the decriminalization of cannabis.

· Dialogue for Hungary (PM)—a green political party in Hungary that was formed in February 2013 by eight MPs who left the Politics Can BeDifferent (LMP) party to be able to cooperate with the Socialist Party.

· Hungarian Liberal Party (MLP)—a small, traditionally liberal party.

· New World People’s Party (ÚVNP)—a conservative Hungarian party founded in 2020 by József Pálinkás, the former Minister of Education under Viktor Orbán and a former member of Fidesz.

· New Start (UK)—a small party advocating a ‘Third Way’ political philosophy founded by György Gémesi, the mayor of Gödöllő, a middle-sized city.

· Everybody’s Hungary Movement (MMM)—a conservative political movement founded by Péter Márki-Zay, the mayor of the middle-sizedcity of Hódmezővásárhely, in 2018.

To decide on joint candidates and a prime ministerial candidate, an opposition primary election was held between 12 and 27 September 2021 (first round) and 10 and 16 October 2021 (second round). This was the first countrywide primary election in the political history of Hungary. The primary elections resulted in a few surprises. The biggest was the winner of the prime ministerial candidacy. A quasi outsider without a real political party, Péter Márki-Zay, the mayor of Hódmezővásárhely, a previous Fidesz stronghold, came in third during the first round, surpassing Péter Jakab, the leader of Jobbik. After intense negotiations which occasionally almost turned into comedy, the second-placed candidate, the mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony eventually stood down in favour of Márki- Zay. Therefore, the final round took place between Márki-Zay and Klára Dobrev, a member of the European Parliament for the DK Party and the wife of former socialist Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány. In the end Márki-Zay won a comfortable victory, gaining more than 56 per cent of the votes. With this, a self-proclaimed Christian, father of seven, former Fidesz sympathizer, and a person new to national politics, without an established party, became the opposition’s prime ministerial candidate. There were surprises in single-member constituencies as well, as several local favourites were defeated by relative outsiders or newcomers. In addition, unexpected political cooperation between the DK and Jobbik parties ensured that these two parties managed to get most of the constituencies. DK won 32 and Jobbik 29, while MSZP won only 18 of the single-member constituencies.9

Although the participation rate was fairly low, according to the opposition about 850,000 voters voted in at least one round of the elections,10 and the primary elections, together with the election of dark horse candidate Márki-Zay, seemed to give a momentum to the united opposition in the autumn. Márki-Zay was seen, especially in the Hungarian and international progressive media, as a candidate who could mobilize disillusioned right wingers and also the youth. This momentum quickly faded, however, mostly because of internal conflicts and the controversial personality of Márki-Zay. For example, only one day after winning the primary, Márki-Zay asked the six opposition parties to allow him to form a seventh parliamentary group and to accept ten candidates to be proposed by him onto the joint opposition list. Later he abandoned this plan, which in practice meant that even if he had been elected prime minister of the country he would have had no faction loyal only to him in Parliament. This, together with the successful cooperation of DK and Jobbik, caused serious friction between the parties, and threatened to unhinge the already very carefully balanced political compromise between the major parties. Later the parties had difficulty in working together and rounding up signatures for their proposed referendum initiative on the planned Fudan University campus and the extension of the jobseekers’ allowance,11 and also faced difficulties and internal strife in finding a joint presidential candidate.12

The controversial and outspoken nature of Márki-Zay also did not help. For example, he regularly advocated for more neo-liberal policies which were not even supported by most of the other parties, he called a pro-government journalist mentally handicapped,13 regularly referred to Fidesz voters from the countryside as stupid and ignorant, and even managed to tell a racist joke which he referred to as ‘cute’.14

The outbreak of war in Ukraine, however, seemed to once again mobilize the opposition, as they hoped they could use the perceived ties between Putin and Prime Minister Orbán to their advantage, and they accused the government of secretly supporting Russia. The government’s strong stance advocating for peace and non-military support to Ukraine, however, resonated more strongly with the majority of voters.

The government’s communication was clear in saying that the needs of the Hungarian economy had to come first

If we look at the polls, we can clearly see that concerns about the war often went hand in hand with concerns about its economic implications. The ultimately successful narrative of the government was twofold: it focused on its ability to preserve peace while also trying to show that it was also the only power able to protect the Hungarian economy against the increasingly dire economic fallout of the war in Ukraine. The government’s communication was clear in saying that the needs of the Hungarian economy had to come first, and while this might have irked some European politicians because of the triumph of naked materialism over ideological and humanitarian considerations, it seemed to resonate with many voters who not only saw Orbán as the guarantor of peace and security, but as the best guarantee against rising energy prices as well.15 The opposition’s firm stance advocating the delivery of military equipment to Ukraine was less popular, which was once again not helped by some ambiguous statements coming from Márki-Zay, not ruling out the possibility of sending Hungarian soldiers to Ukraine.

The Result: a Historic Victory for the Right

Despite these difficulties, the united opposition remained hopeful and approached the elections with great expectations. Most of the opinion polls showed a slight Fidesz lead but some of them, especially the more liberal ones, saw only a 1–2 per cent lead, or saw the two blocs tied.16 The minimum the opposition was hoping to achieve was to deny Fidesz another two-thirds majority, and—based on their 2019 local election result—pick up some single-member constituencies, especially in the agglomeration of Budapest and in some of the major cities in the countryside.

A site originally established to promote tactical voting between the different opposition parties, for example, predicted that there were at least 37 single-member constituencies which the opposition had a better chance of winning than Fidesz (Figure 1). In some major cities like Dunaújváros, Pécs, Miskolc, Nyíregyháza, and Szeged, they predicted that the opposition might even have about a 10 per cent lead over Fidesz. There was similar optimism in parts of the agglomeration of Budapest, such as Érd, or Dunakeszi, and they even thought that the opposition had pretty good chances in some county capitals like Békéscsaba, Kaposvár, or Tatabánya. These expectations were, however, mostly not realized in the end, and the opinion polls failed to predict how popular Fidesz really was.

Looking at the final party lists, with 54.13 per cent of the popular vote, Fidesz received the highest vote share, both in percentage terms and in the number of votes, of any party in Hungary since the fall of communism.17 Fidesz received 4.8 per cent, about 236,000 more votes than four years before. Although they lost four single-member constituencies compared to their result in 2018, they managed to retake the Dunaújváros district and all their losses were in Budapest. They still managed to win 87 out of the 106 single-member constituencies (86 out of 88 districts in the countryside), which means that, for example, in the British system, Fidesz would have an 82 per centmajority in Parliament. While losing the three traditionally conservative Buda districts in the capital is certainly a prestige blow for Fidesz, they have managed to outperform their past result almost everywhere else in the country. The party got significantly more votes in the northwestern, south-central, and eastern parts of the country (see figures 2 and 3). There were several districts where government candidates increased their lead by more than 8 per cent, and various districts where the Fidesz candidate received more than 60 per cent of the votes. The party in the end managed to secure 135 places out of 199 in Parliament, securing another supermajority.

The results were less encouraging for the united opposition. They performed 10–11 points below the result anticipated by themajor polling companies, and five points below even the most pessimistic major poll.18 Perhaps even more significantly, they lost more than 14 per cent and about 900,000 voters compared to the overall results of the 2018 elections. In 2018 these parties together received more than 2.7 million votes, which translated to 47 per cent, while Fidesz received 2.8 million votes, which was a bit more than 49 per cent. Now the opposition only received 1.9 million votes, which amounts to only 34 per cent, while Fidesz managed to increase its votes to somewhat above three million.

The only positive result the united opposition can show, and which conformed to their previous expectations, is that they managed to win a sweeping victory in the capital, getting 17 out of the 18 districts. But even in Budapest the difference between the two blocs was only 7 per cent, roughly the same as in the 2019 local elections, so most likely the opposition was unable to significantly increase its vote share even in the capital. In the countryside, they did hold on to their two districts from 2018 in Pécs and in Szeged, but lost the district of Dunaújváros. More troubling for the opposition is that not only did they fail to gain some major cities and pick up some seats in the agglomeration of Budapest, but Fidesz candidates actually managed to raise their vote share in most of these districts such as Miskolc, Nyíregyháza, or the second district of Pécs.

The success of the new far-right party called Mi Hazánk Mozgalom (literal translation: Our Homeland Movement) also surprised the opposition and most pollsters. Mi Hazánk was actually established by disillusioned former Jobbik party members and supporters who were unhappy with the left-wing turn of the party and its alliance with the other opposition parties. Mi Hazánk received almost 6 per cent of the vote, and therefore will have 6 members of parliament. This is a significant success for a party which was only established in 2018, even if they could most likely partly count on some local Jobbik organizations that switched to their side. Beside Mi Hazánk, no other party managed to reach the five- per-cent threshold. The joke party called the Hungarian Two Tailed Dog Party came the closest with 3.27 percent.

The success of the new far-right party called Mi Hazánk Mozgalom surprised the opposition and most pollsters

Aftermath and Conclusions

The most important conclusion of the election is that the rainbow coalition envisioned in the opposition party headquarters and progressive think tanks did not necessarily resonate with the wishes and expectations of the Hungarian voters. Politicians might accept compromises and accept positions which are completely opposite to their own, but it seems that voters are less willing to.

Most analyses focused on how former Jobbik voters did not show up to vote or voted for Mi Hazánk or Fidesz, but the real picture appears somewhat more nuanced. Sadly, we do not have detailed, reliable demographic exit polls, so the only verifiable data we can use is territorial data coming from the voting districts themselves. The electoral turnout was 69.54 per cent, slightly below the 70.22 per cent of 2018, but still historically high, as it was the third highest since the fall of communism. So it is very unlikely that most of the almost one million Jobbik voters from 2018 did not show up. This is also supported by the fact that while turnout was a bit lower in districts where Jobbik was the strongest opposition party in 2018, this was not a significant factor. It is also true that in these districts the opposition generally did worse than in 2018, so a significant number of Jobbik voters did turn up to vote and voted for other parties. It is estimated by experts that about 250,000 former Jobbik voters chose Mi Hazánk, while about 120,000 voted for Fidesz.19 However, we can see another surprising trend as well: the opposition lost a significant number of voters in small to middle-sized cities in the countryside, with populations of 5,000– 20,000. These cities, such as Tiszaújváros, Hatvan, or Törökszentmiklós, are mostly located in the eastern part of Hungary, and were historically strongholds of the left. In these cities, it is estimated that the opposition lost about 300,000 votes, and while some of these could have been Jobbik voters, it does not explain the total volume. Based on this, it would appear that not only did Jobbik voters refuse to vote for socialists or liberals, but some traditionally socialist voters also refused to vote for the formerly far-right Jobbik.

The election results also show that the narrative claiming that Fidesz is the party of older, poorer, uneducated rural people is simply not true

The election results also show that the narrative claiming that Fidesz is the party of older, poorer, uneducated rural people is simply not true (compare the data for the 2018 and 2022 elections in figures 4 and 5). Fidesz is currently the strongest party in basically all the major demographic categories. For example, if we look at the parties individually, Fidesz is actually the most popular party even among those under thirty.20 The strong showing of Fidesz in the agglomeration of Budapest, where some districts actually have higher living standards and a better educated populace than most of the capital, also indicates that there were significant numbers of highly educated, better-off voters who benefit from the economic policies of the current government and therefore voted for the governing party. It also shows that the perceived urban–rural divide in Hungary is mostly a Budapest versus the rest of the country divide. Of course, generally speaking the opposition received more votes in the major cities than in rural areas, and Fidesz dominated the rural areas more than the cities, but overall Fidesz is still the strongest party in most of the major cities as well.

Naturally, the opposition will find some scapegoat, from Márki-Zay to the perceived media dominance of Fidesz or the war in Ukraine, but the hard truth is that the problems facing the opposition are much deeper. Péter Márki-Zay certainly did not deliver what was expected of him, namely that he would appeal to more rural and conservative voters. Also, with the current widespread internet access in Hungary, perceived media dominance simply could not be the ultimate cause of the opposition’s weak positions outside of Budapest, a fact that was acknowledged by several left-wing think tanks as well.21

The opposition currently faces two challenges. First, they sadly do not have an appropriate organizational network and community in the countryside. This was not always the case. After the fall of communism, building on the organization of the former communist state party, MSZP had the greatest political network and capital in the countryside. It took almost two decades for conservatives to build up their networks in the countryside, which the opposition, with the fragmentation of MSZP, has simply lost over the past ten years. The primaries also did not necessarily help this process, since as so often with political compromises, people without local knowledge become the candidates. Without a real presence and community in the countryside, the opposition has no real chance of defeating Fidesz.

A second problem is more political. Sadly, after more than ten years, the leading power of the opposition is still DK, led by the discredited former socialist Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány. Gyurcsány is still popular with a fragment of the population, but most voters have highly unfavourable views of him. Several parties of the united opposition, such as Jobbik, LMP, or Momentum, were explicitly established to form an alternative to both Fidesz and the old discredited left and people like Gyurcsány. By agreeing to cooperate with him, these parties both abandoned the wishes of the electorate and gave ample political ammunition to Fidesz and the right-wing media, which they exploited ruthlessly during the electoral campaign. In my humble opinion, if the opposition wants a chance to defeat Fidesz, besides building a stronger presence in the countryside, they will also have to finally break away from the past and heavily discredited politicians like Ferenc Gyurcsány. This will not be easy, but their alternative is merely another two-thirds supermajority for Fidesz in 2026.

NOTES

1 The New Hungarian Electoral System (Századvég: 2013), www.scribd.com/document/165062712/ THE-NEW-HUNGARIAN-ELECTORAL- SYSTEM?ad_group=2250368&campaign=VigLink& content=27795&irgwc=1&keyword=ft500noi& medium=affiliate&source=impactradius#download.

2 These are the following: Armenian, Bulgarian, Croatian, German, Greek, Polish, Romani, Romanian, Rusyn, Serbian, Slovakian, Slovenian, and Ukrainian.

3 This is about one quarter of the votes required by the normal parties.

4 See the latest government statistics, https:// kormany.hu/hirek/a-cselekvo-nemzet-eve-lesz-2022.

5 Political Capital, ‘Külhoni magyar állampolgárok nélkül is meglenne a kétharmad, a győztes túljutalmazása nélkül nem’ (There would be a two- thirds majority even without the votes of Hungarians living abroad, but not without the over-rewarding of the winner), (11 April 2022), https://politicalcapital.hu/ hirek.phparticle_read=1&article_id=2991.

6 Hungarian Socialist Party, Dialogue for Hungary, Politics Can Be Different, Democratic Coalition, Momentum Movement, Hungarian Two Tailed Dog Party, Together.

7 The most important document in this regard was perhaps from the Republikon think tank. See ‘Előválasztási javaslat’ (A Proposal for the Primaries), Republikon Intézet (10 March 2020), http://republikon. hu/elemzesek,-kutatasok/200310-elovalasztas.aspx.

8 These are the so-called ‘cities with county rights’, as most of them are the capitals of the nineteen counties of Hungary.

9 Momentum won 15, PM 6, and LMP 4.

10 Based on the statistics coming from the organizers of the primary elections, https://elovalasztas2021.hu/ eredmenyek/.

11 Ábrahám Vass, ‘Opposition Has So Far Collected 170,000 Signatures for Referendum on Fudan and Jobseeker’s Allowance’, Hungary Today (14 January 2022), https://hungarytoday.hu/opposition-signature- referendum-china-fudan-jobseekers-allowance/.

12 Péter Cseresnyés, ‘Opposition Steps Back from Organizing Primary to Choose Own Presidential Candidate’, Hungary Today (22 November 2021), https://hungarytoday.hu/opposition-steps-back- organizing-primary-to-choose-own-presidential- candidate/.

13 ‘Press Roundup: Márki Zay Calls Pro-Gov’t Journalists “Handicapped”’, Hungary Today (26 January 2022), https://hungarytoday.hu/marki- zay-handicapped-press/.

14 ‘Left’s PM Candidate Cracks a Racist Joke on Social Media’, V4 Agency (17 February 2022), https://v4na. com/politika/lefts-pm-candidate-cracks-a-racist-joke- on-social-media-67349/.

15 András Bíró and Gábor Győri Nagy, ‘Hungarian Parliamentary Elections 2022’, FES Briefing, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (3 April 2022), http://library. fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/budapest/19126.pdf.

16 Závecz Research for example saw a 2 per cent Fidesz lead, while the last poll before the elections conducted by Publicus, at the end of March, saw Fidesz and the united opposition tied on 47 per cent each; see https://hungarytoday.hu/survey-pollster- predict-fidesz-mi-hazank-opposition-surprise- election-vote/; and https://publicus.hu/blog/partok- tamogatottsaga-2022-marcius-vege/.

17 All the electoral data presented in this article are from the website of the Hungarian National Election Office, see www.valasztas.hu/web/national-election-office.

18 Bíró and Győri Nagy, ‘Hungarian Parliamentary Elections 2022’.

19 Bence Stubnya, ‘900 ezer eltűnt ellenzéki szavazó, totális Fidesz dominancia – a választások eredményeit elemeztük’ (900,000 Vanished Opposition Voters, Total Dominance of Fidesz—We Analysed the Results of the Election), G7 Podcast (9 April 2022), https://g7.hu/podcast/20220409/900-ezer-eltunt-ellenzeki- szavazo-totalis-fidesz-dominancia-a-valasztasok- eredmenyeit-ertekeltuk/.

20 Krisztina Kincses, ‘Nem igaz, hogy a fiatalok a baloldalra szavaznak’ (It Is Not True That the Youth Vote for the Left), Magyar Nemzet (13 April 2022), https://magyarnemzet.hu/belfold/2022/04/nem-igaz- hogy-a-fiatalok-a-baloldalra-szavaznak.

21 See for example Méltányosság Centre for Policy Analysis, https://meltanyossag.hu/en/what-happened- in-hungary/.