The new right today faces a dilemma. It is increasingly unclear what its core mission is. Is it to try to maintain the global dominance of Western nations? Or is it to remedy the severe problems that have been visited on Western nations by late liberalism? In politics, as in engineering, the amount of energy available for any given operation is always limited—and if that energy is misspent on one project, it will not be available for another. The energy levels in Western countries today—looked at culturally, socially or economically—are very low. Any political actors looking to promote reforms must understand this.

But even beyond the simple question of energy and attention, there is a deeper one. Can Western nations hope to resurrect Western hegemony while remaining so dysfunctional domestically? Deeper still: are some of these domestic dysfunctions a direct result of their role in maintaining a liberal empire in its late stages? Viewed this way, the emerging multipolar world might not be a problem for the new right—or not only a problem. It might also present opportunities for cultural and political revitalization in the West.

Decivilization and Recivilization

At a meeting of his Council of Ministers in May 2023, French President Emmanual Macron said that there was a ‘process of decivilization’ underway in the French Republic. Macron’s speech was a response to some recent events in France, but these were just markers on a road of general chaos that France has been travelling for some time. The French press panicked when Macron used this phrase, seeing in it an echo of the infamous reactionary writer Renaud Camus’ 2011 book, Décivilisation.[1]

Perhaps, however, Macron has pointed the way forward. What may be desperately needed now is a process of ‘recivilization’. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term was put into circulation in the revolutionary 1790s. Since then, it has not received much further use. But it seems to do justice to what is needed in the West. Thomas Carlyle referred to an ‘effulgence of recivilisation’ in the 1830s, and we should work to see the same in the 2030s.[2]

The need for recivilization comes at the same time as some in Western conservative circles fret over the resurgence of an ancient civilization-state: China. Why have conservatives on the new right become so fixated on China? Some of this is rational. The United States certainly did lose significant amounts of manufacturing jobs to China—although this was effectively a joint decision between the United States and China. But much of it is questionable and appears to due to some on the new right trying to substitute China for the Soviet Union as a foe—or a spectre—against which American energies can be concentrated. One senses that deep down many on the new right do not care all that much about China but mainly see it as a chance to summon people to the ideas that they do care about. As we are seeing with the failures of the Trump administration in trying to launch a trade war with China, this is misguided even as a political strategy.

‘For the past century at least, conflict has been the main cause of decivilization in the West’

Whether conflict has ever recivilized those engaged in it is perhaps an open question. But for the past century at least, conflict has been the main cause of decivilization in the West. The steep decline of the West that we are currently experiencing can be traced back to the First World War which destroyed the old structures of Europe, led to an outbreak of nihilism in the culture, and ultimately led to the Second World War. How anyone could look at the history of the 20th century and argue that the solution to our current problems is yet more conflict is a mystery.

Estranged Cousins

The reality is that modern Western culture cannot be understood without acknowledging the profound impacts China has had on the West, especially in the early modern period.[3] Likewise, modern Chinese culture cannot be understood if we ignore the massive impact that Western culture has had, especially in the long 20th century. The extent to which China remains a socialist country is open to debate, yet it cannot be denied that China’s state structures and national mission refer to the formative influence of Marxism—and Marxism is a doctrine that cannot be understood outside of the historically Christian culture from which it emerged.[4] Chinese Marxism inculcated into modern China certain hopes and ideas that are central to Western thinking—and indeed, to Christian religion.

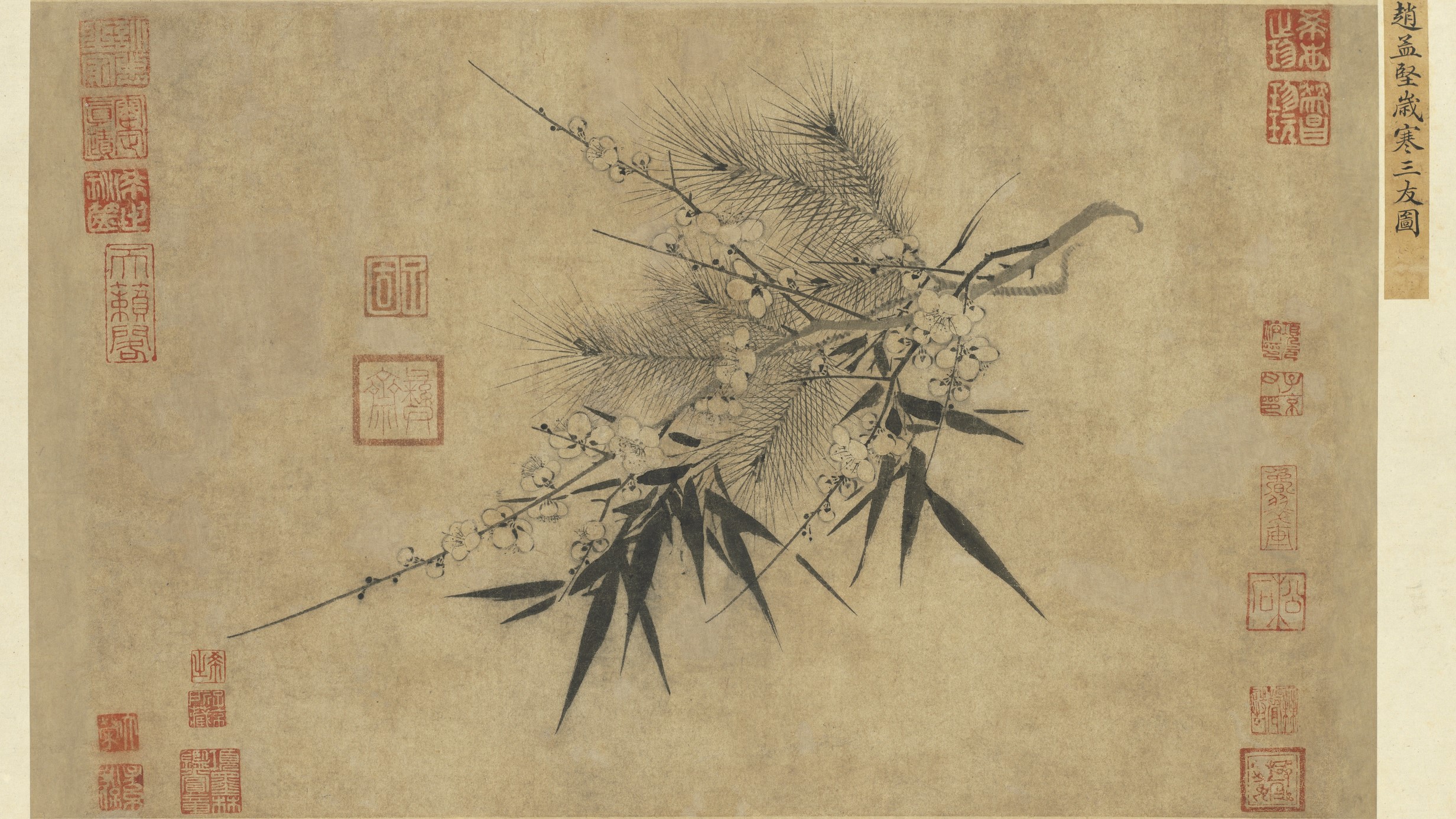

The roots of Chinese influence on Western culture antedate the Enlightenment. The main driver of this influence was a vast expansion of global trade in the 16th and 17th centuries.[5] Due to the effective control of ports like Canton (now Guangzhou) the Western elite saw a flood of Chinese luxury products appearing in salons and drawing rooms across Europe. These included Chinese silk, porcelain, and of course tea. During this so-called ‘China craze’ European elites saw owning Chinese products as a mark of sophistication and class status. Luxury porcelain products were a notable status symbol in the early modern period. It is by no means accidental that ‘china’ came to refer to fine ceramics in Western Europe—as it still does.

‘The image that most Westerners have in their minds of “high European culture” is heavily influenced by Chinese aesthetics and style’

King Louis XIV was one of the iconic figures who set these Asiatic fashions in motion. His fabulous palace at Versailles became a showcase for Chinese-inspired aesthetics, which became known as ‘Chinoiserie’, a new European style that sometimes drew upon, and sometimes played with ancient Chinese motifs. The king’s apartments and salons featured extensive collections of Chinese porcelain. As is often the case, these fashions spread from the king’s palaces to the dining rooms of the lesser nobility across Europe. The result has been that the image that most Westerners have in their minds of ‘high European culture’ is heavily influenced by Chinese aesthetics and style.[6] This was never a simple importation of Chinese culture, but rather a dialogue between Chinese and Western aesthetics which gave rise to some of the most impressive art, décor and architecture in human history.

‘Sinophilism was not a phenomenon restricted to one particular country in Europe. It was widespread and dynamic…and it left a residue of cultural and intellectual influences assimilated by the West so completely that their presence is seldom discerned.’[7]

What is more, Chinese trade flows markedly impacted modern Western thinking on economics. The excellent quality of exotic products that were arriving in Europe set minds racing about what sort of society could produce these goods and on what type of economic model it was based. Modern scholarship has shown that this type of thinking had a major impact on economic thinkers of the Enlightenment, such as François Quesnay:

‘[T]he economic impact of China on the West may be greater than has generally been supposed. Aside from the question of trade relations between East and West whose effects have been frequently mentioned, consider the effects of laissez faire economics, noticeable principally in the 19th century but discernible even today—concepts which can be traced back through Adam Smith and the physiocrats to China. There can be little doubt that China was Quesnay’s model [for a laissez faire economy]. His students openly attested to that fact, and the affinity between his economic thought and what he conceived was being practiced in China is irrefutable.’[8]

Disrupted Commerce

The impact that Chinese culture had on European aesthetics, via trade, soon started to seep into the Enlightenment mentalité more broadly.[9] Here we must distinguish between two types of influence: direct influence of China (or Chinese goods) in the West, and the influence that certain ideas about China may have had (whether or not they were accurate). As noted by an American Sinologist, Edmund Leites, ‘the influence of China upon European culture’ is not to be confused with ‘the reception of (what was taken to be) knowledge of China or Chinese philosophy by Europeans.’[10]

Much of the impact that Chinese ideas (and ideas about China) had on the nascent Enlightenment emerged out of the religious debates about the nature of Chinese Confucian culture that were introduced into the West by the Jesuits.[11] These debates focused on a problem that we might call virtuous atheism or immanent virtue. Everyone in Europe granted that Chinese society was highly advanced and yet was not based on a recognizably monotheistic religion, much less on Christianity. Jesuit thinkers immersed themselves in the arcana of Chinese thought to try to find the underlying basis of their virtue—which they found in the Chinese concept of Li, meaning roughly ‘ordering principle’ or ‘ritual’.

In both Jesuit and secular circles in the West, Li was often held to be a noble ‘combination of nature and morality’—or what we might call natural law.[12] This is most subtly explored in texts by the German polymath, G W Leibniz, who was fairly obsessed with China.[13] Yet the theistic interpretation of Li proved extremely controversial in Catholic theological circles:

‘Accordingly, the doctrine that “Li” as formulated in classical Chinese thought was derived from prisca theologia and is thus a memory, notion or premonition of the providential God of the Christians, the thesis upheld by the Jesuit Confucianists…was roundly condemned as ‘error’ by Paris’ Sorbonne University in the year 1700.’[14]

‘In both Jesuit and secular circles in the West, Li was often held to be a noble “combination of nature and morality”—or what we might call natural law’

This rejection of Jesuit thinking on the Li concept proved, like so many other decisions taken in the counter-Reformation period, to be a mistake.

By condemning the Jesuits’ sympathetic reading of Li, the doctors of the Sorbonne inadvertently sided with a rising tide of European thinkers who were thrilled by the idea that Chinese virtue might be atheistic or pantheistic in inspiration. The very subtle question of whether the Confucians were, in fact, atheists or pantheists, served to link ancient Chinese philosophy to the hotly contested modern legacy of Benedict de Spinoza—who was himself, depending on who you asked, a pantheist or an atheist. The Calvinist skeptic Pierre Bayle, for instance, ‘deliberately equated’ the views of Spinozists in Europe and the litterati in China (les Spinozistes et les Lettrez de la Chine).[15]

Many Enlightenment critics of religion seized on what they saw as the atheistic, or non-theistic virtues inherent in Chinese culture. ‘I can scarcely refrain from saying: “Sancte Confuci, ora pro nobis”’—Holy Confucius, pray for us!—as the French skeptic François de La Mothe Le Vayer once mischievously said.[16] The 18th-century direction of travel is unmistakable:

‘Sinophilism developed into Sinomania as Montesquieu, Voltaire and a score of lesser writers enthusiastically proclaimed the virtues of the great Oriental culture.’[17]

Conservatives may look at these early modern debates and conclude that Chinese cultural penetration into early modern Europe had a negative impact on the West by strengthening the philosophes’ case that a highly civilized culture could be founded on atheistic principles. First, this is historically doubtful. Skeptical writers brought similar arguments against Christianity by drawing on Greco–Roman sources and arguing that the classical world had prefigured Enlightenment ideals. These debates are well-known, and the Christian response has always been to highlight, for example, the implicit monotheism of the Platonic tradition.[18] Second, and more importantly, it was the Christian theologians who opposed a more sympathetic engagements with Chinese thought who gave the opening to skeptics and libertines. Today we can see that this Western decision led gradually to a disruption of what Leibniz liked to call a ‘commerce of light’—a high-minded interchange of thought and culture—between China and the West.[19]

As China resumes its place as a great power on the world stage, perhaps it is time to reengage with some of the arguments of the Jesuit Confucianists. We really have no choice. Once we understand how extensively Chinese culture has influenced modern conceptions of Western culture, we realize that taking its influence into account is integral to any honest effort at recivilization in the West.

[1] Renaud Camus, Décivilisation, Paris, Fayard, 2011. See further: Marc-Olivier Bherer, ‘En parlant de “décivilisation”, Emmanuel Macron utilise un concept malléable à souhait’, Le Monde, 31 May, 2023. Archived online at https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2023/05/31/en-parlant-de-decivilisation-emmanuel-macron-utilise-un-concept-malleable-a-souhait_6175507_3232.html, accessed 15 June 2025.

[2] According to the Oxford English Dictionary entry for ‘recivilization’ archived online at OED.com, accessed 15 June 2025.

[3] A classic treatment is René Etiemble, L’Europe chinoise, I: De l’Empire romain à Leibniz, Paris: Gallimard, 1988; and L’Europe chinoise, II: De la sinophilie à sinophobie, Paris: Gallimard, 1989.

[4] Jacob Taubes, Occidental Eschatology, trans David Ratmoko, Palo Alto, Stanford University Press, 2009.

[5] Donald F Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume I: The Century of Discovery, Book 1, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1994.

[6] Oliver Impey, Chinoiserie: The Impact of Oriental Styles on Western Art and Decoration, London, Oxford University Press, 1977; Anne Witchard (ed), British Modernism and Chinoiserie, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2015.

[7] W W Davis, ‘China, the Confucian Ideal, and the European Age of Enlightenment’, Journal of the History of Ideas 44, no. 4 (1983), 523–48, p. 545. (Our stress.)

[8] Ibid, p. 546.

[9] Donald F Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume II. A Century of Wonder, Book 3: The Scholarly Disciplines, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994.

[10] Cit Stefan Gaarsmand Jacobsen, ‘Chinese Influences or Images? Fluctuating Histories of How Enlightenment Europe Read China’, Journal of World History 24, no. 3 (2013), 623–60, pp. 637–38.

[11] David E Mungello, Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology, Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 1985. See further: J J Clarke, Oriental Enlightenment: The Encounter Between Asian and Western Thought, London, Routledge, 1997; David Porter, Ideographia: The Chinese Cipher in Early Modern Europe, Palo Alto, Stanford University Press, 2002.

[12] David E Mungello, ‘Leibniz’s Interpretation of Neo-Confucianism’, Philosophy East and West 21, no. 1 (1971), 3–22, pp. 20–21.

[13] G W Leibniz, Writings on China, Daniel J. Cook and Henry Rosemont (ed and trans), LaSalle, Illinois, Open Court, 1998.

[14] Jonathan Israel, ‘The Battle over Confucius and Classical Chinese Philosophy in European Early

Enlightenment Thought (1670–1730)’, Frontiers of Philosophy in China 8, no. 2 (2013), 183–98, p. 191.

[15] Ibid, p. 188.

[16] Arnold H Rowbotham, ‘The Impact of Confucianism on Seventeenth Century Europe’, The Far Eastern Quarterly 4, no. 3 (1945), 224–42, p. 230. (Our stresses.)

[17] Ibid, p. 232. (Our stresses.)

[18] Nor is this only a Christian argument: See Stephen Mitchell and Peter Van Nuffelen (eds), One God: Pagan Monotheism in the Roman Empire, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

[19] Franklin Perkins, Leibniz and China: A Commerce of Light, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Related articles: