To answer the question with whom and what conservatism is typically associated with, most would cite the political pamphlet ‘Reflections on the Revolution in France’, widely regarded as the foundational text for the conservative school of thought, and its author, Edmund Burke, is often credited as one of its principal theorists. Although there is no strict criterion for determining who the other key figures within conservative political thought are, it is common for those seeking to familiarise themselves with conservative ideas to explore the works of such renowned thinkers as Joseph de Maistre, Carl Schmitt, Michael Oakeshott, or Roger Scruton, to name just a few.

There has been, however, a multitude of other esteemed intellectuals whose work is not directly related to politics or philosophy who came to the same conclusions and uncovered truths similar to those traditionally attributed to conservative thinkers. Interestingly, some compelling examples of this phenomenon can be found even in fields far removed from the traditional intellectual domains of conservatism. Take, for instance, the works of the Polish science fiction writer Stanisław Lem, a figure perhaps rarely quoted in this context. Lem’s ideas intriguingly echo conservative principles despite their originating in a vastly different sphere.

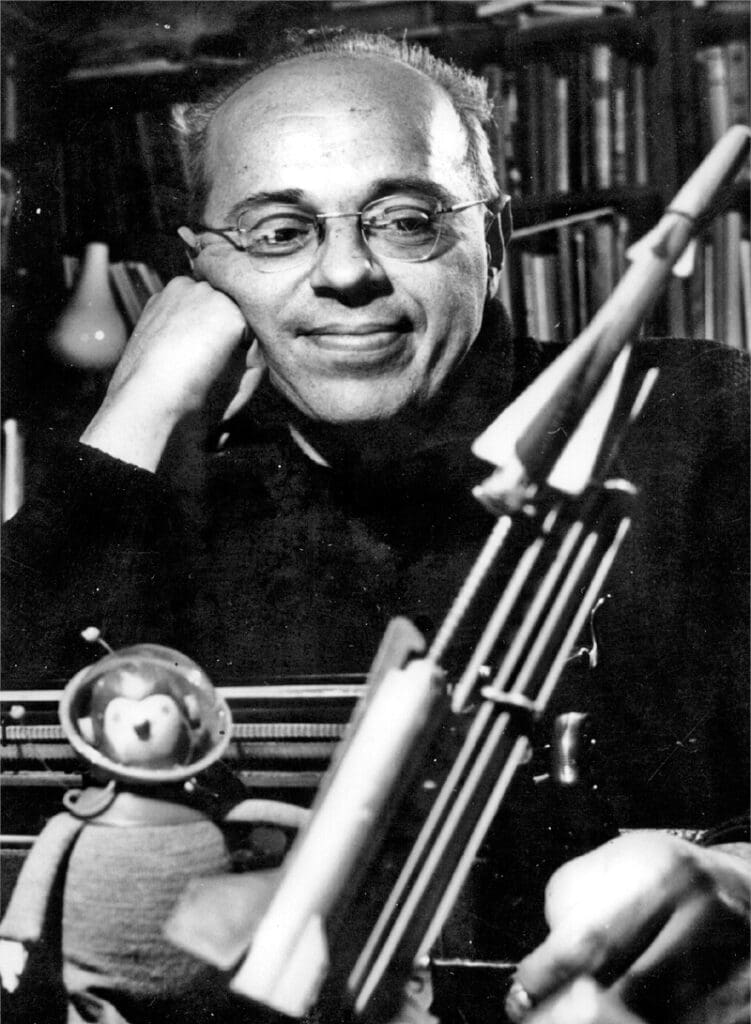

Stanisław Lem (12 September 1921 – 27 March 2006) was a Polish author who was widely known in the Socialist block and beyond for his science fiction novels, such as Solaris, Eden and Fables for Robots, Many other works of his are also classics of the genre. His enormous success is well demonstrated by the fact that his books have been translated to 40 languages and have sold over 45 million copies worldwide. He was recognised for his contribution to literature with several awards, including the Austrian State Prize for European Literature in 1986, and the Order of the White Eagle, Poland’s highest decoration in 1996.

Unfortunately, less known is the fact that

Stanisław Lem was also a prolific essayist and philosopher,

with one of his nonfiction works, Summa Technologiae (1964) being considered a masterpiece of speculative non-fiction and philosophy of technology. While the majority of the essays collected in the book is to explore potential future technologies (paraphrasing the author, to ‘examine the thorns of roses that have not flowered yet’), Lem demonstrates that he is not entirely optimistic about technological progress, especially about its ethical implications. Despite being enthusiastic, creative and thoughtful in his futurological prognoses (envisioning many technologies that later materialised, such as the Internet, virtual reality and many others), he made it clear that he is not naïvely optimistic about the technologies of the future, especially in terms of their potential effect on human morals.

To understand his scepticism, one must understand his views on societal development. According to his writings, Stanisław Lem viewed societal development, as well as biological and technological evolution, as a process towards the achievement of the state of homeostatic equilibrium. As he put it: ‘Homeostasis—a sophisticated name for aiming toward a state of equilibrium, or for continued existence despite the ongoing changes—has produced gravity-resistant calcareous and chitinous skeletons; mobility-enabling legs, wings, and fins; fangs, horns, jaws, and digestive systems that enable eating; and carapaces and masking shapes that serve as a defence against being eaten. Finally, in its effort to make organisms independent of their surroundings, homeostasis implemented the regulation of body temperature. In this way, islets of decreasing entropy emerged in the world of general entropic increase.’ Whereas animals can count only on once-in-a-millennia mutations in order to adapt to the environment, Humanity has the capability of both adapting to and transforming the environment quite quickly and repeatedly, by utilizing technologies. The very history of our civilization, that Lem describes as ‘its anthropoid prologue and its possible extensions,’ is thus seen as a process of expanding the range of homeostasis—which is a way of defining humanity transforming its environment—over several thousands years.

While technology has a remarkable effect in helping humanity transform the environment or to help it adapt to it, according to Lem, technology is nevertheless double-edged. In fact, technology is not always helpful in establishing homeostasis, on the contrary: technology often undermines it. Just as technology shifts the dynamic homeostatic equilibrium in the realm of the material (e.g. the side effect of using pesticides to kill insects is the destruction of the entire ecological structure in a given area), it is also important to recognise how technologies and the simplification of life they achieve can destroy the value of homeostasis.

Lem offers the transformation of the relations between the sexes as an example. Whereas in the past, claims Lem, people, due to the culturally-created difficulties exemplified by rituals and traditions, valued the acquisition of love more, the technologies such as contraception that ‘simplified the process’ of accessing sexual pleasures had a side effect of devaluing this feeling and, as a result, weakening the romantic emotions between the sexes. While Lem formulated this idea in the 1960s, it is hard not to acknowledge how right he was and to what extent the issue is even more aggravated by newer technologies such as free access to one-night dating apps and unlimited sexual content popping up unsolicited everywhere on the internet.

By simply calling some traditions ‘irrational’ or ‘obscure’, Lem writes, and disregarding them as unneeded obstacles, one cannot achieve any adequate solution to the existing problems in this realm. Cultural norms came into being with clear clear purposes: they awaken the passion for competition, teach how to overcome obstacles, strengthen resistance to stress and thus form the structure of the personality. This observation is not related just to the sphere of sexual relations. Free access to information, for one, has significantly devalued every piece of knowledge a human can obtain, and reduces the chance of learning anything properly. While in an jokingly ironic manner that is very characteristic of his writings Lem proposes the setting up of a ‘Ministry of Common Hardships’ whose task is to come up with obstacles for the problem-free people of the future, it is clear for the reader that the message is more than serious.

The conclusion Lem reaches is that exchanging values for comfort, enabled by technologies, will eventually shift the organically developed axiological (i.e. value-related) equilibrium, thus undermining the societal homeostasis, posing a direct threat to societal reproduction and survival. Contrary to what one might expect from a science fiction writer and futurologist, Lem decides that technology will never substitute values as a guiding light for cultures, thus, ultimately, deeming techno-optimism wrong. Technologies can be useful tools, but not the ideal nor the ultimate goal, he argues. At the same time, he believes that it is impossible to stop a technology after it has been released, warning that other means of defending the core of civilization must be developed to make it immune to the overarching spread of some invasive technologies.

It’s fascinating to discover how insights into conservative ideology can occasionally emerge from the most unexpected source, such as the complex and insightful works of essayist, philosopher and speculative fiction writer Stanisław Lem. This exemplifies that conservative perspectives can organically manifest in the thoughts of a diverse array of intellectuals, even those without traditionally conservative backgrounds. Such instances foster the optimism that conservative principles have the potential to resonate and find fertile ground within a broad spectrum of minds, despite the varied terminologies they might use to categorise their ideas.