The second volume of Oswald Spengler’s (1880-1936) great work, The Decline of the West, was published almost exactly a century ago, in 1922.[1] Spengler’s book has not lost its relevance at all in the past century, and has even retained its importance to this day. Although many people, historians and philosophers alike, attacked Spengler’s work—for example, for its strongly speculative and non-scientific nature—The Decline of the West preserved its appeal.

Although the book undoubtedly contains exaggerations and historical inaccuracies, many of his predictions about the fate of humanity, made a hundred years ago, can be quite well applied to global society and to the conditions of today’s world of politics. In connection with the present topic, especially the observations that Spengler made in relation to culture and civilisation are of interest to us, even if we can only talk about certain analogies here, not ‘prophecies that have come true.’

In today’s general use of language, the concepts of civilisation and culture can even be substituted: since there is no uniform definition, culture and/or civilisation ‘mean too much and too little at the same time.’ (T. S. Eliot.) However, we can say that if they are used in a sense related to the philosophy of history, then the concepts of culture and civilisation obtain a range of meanings that represent the uniform development of different countries, parts of the world, or human communities according to a linear approach to history. The European Union was born on 1 November 1993 precisely in the spirit of such principles of unification and development.

The European Union is an organisation that—at least according to the optimistic premise of European politicians—will eliminate the blocs of the Entente and the Axis formed during the 19th and 20th centuries,

thereby ensuring that a new ‘European World War’ (John Lukacs) is avoided. At the same time, at least according to the optimistic plans, the Union also creates a balancing power factor between the USA and Russia that prevents the continent from being colonised by non-European powers, while ensuring the free flow of capital and goods in the spirit of free competition capitalism.

The European Union was organised in the spirit of a political idea that viewed the future with a fundamentally optimistic attitude. One of its immediate predecessors, the International Pan-European Union, was established in 1924, two years after the birth of the second volume of The Decline of the West, and right after WWI. Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, in his Pan-European Manifesto, a pamphlet written in liberal spirit, outlined the image of Europe unifying itself against the threat of the communist Soviet Union for the sake of ‘peace and progress.’

‘The fragmented Europe is therefore approaching a triple catastrophe: the annihilating war; submission by Russia; towards economic collapse. The only escape from this looming catastrophe: Pan-Europe; the political and economic union of the democratic countries of continental Europe.’[2]

In the same pamphlet, Coudenhove-Kalergi called for the realisation of the ‘United States of Europe’ and emphasised that pan-Europe is not a utopia, but a programme for the realisation of which all Europeans who love their country must fight.

In the same years that Kalergi proclaimed the fight for pan-Europe, Spengler proclaimed a much more pessimistic vision of the future. He emphasised that the different viewpoints of the idea of historical progress are all utopian, since history itself is a phenomenon of life, its processes cannot be determined based on abstract criteria and preferences and ‘secured’ in this way. Spengler contrasted the concepts of culture and civilisation in The Decline of the West. While in the Anglo-Saxon world the distinction between the two was not, or was not willing to be made, Spengler emphasised that culture is of a higher order, more essential and more important than civilisation, which is merely the externalisation, solidification of the former. If he would have lived longer, in the global unification processes after the Second World War, he may have seen the disappearance of diversity, the exhaustion of creative impulses and the arrival of the world of uniformity, greyness, and following global patterns rather than the fulfilment of freedom.

According to Spengler, culture—like history—is a phenomenon of life, i.e. it stands before us as a kind of living being, an organism, which, like physical organisms, has some kind of specific spirituality, essence, and individual nature. The birth of a culture cannot be traced back to purely material processes, or even decisions of the will, just as the birth of humans, animals and plants requires an act of conception that assumes a non-rational, spiritual starting point. This cannot simply be derived from material processes and calculations.

As Spengler writes:

‘A Culture is born in the moment when a great soul awakens out of the protospirituality [… ]of ever-childish humanity, and detaches itself, a form from the formless, a bounded and mortal thing from the boundless and enduring. It blooms on the soil of an exaccly-definable landscape, to which plant-wise it remains bound. It dies when this soul has actualized the full sum of its possibilities in the shape of peoples, languages, dogmas, arts, states, sciences, and reverts into the proto-soul.’[3]

However, in the eyes of the philosopher, European culture, which Spengler connected above all with the ‘Faustian man’, from the beginning of the 19th century transformed itself into a European civilisation which gradually loses its creative, living spirit and is subordinated to the ‘bureaucratic authority’ (Max Weber) and the growing processes of technical rationality. From small towns big cities and finally metropolises emerge, giant cities where all political, economic and industrial complexes are concentrated, and which are practically the centre of life and people’s work.

The ‘Pan-European plans’ of the creation of a unified European culture suggested that the periods preceding modern civilisation, which has now practically become global, can be evaluated in the history of mankind from the point of view of the extent to which they helped humanity develop the most suitable form of political modernity, ‘liberal democracy.’ Just as the words democracy and democratic feature prominently in Kalergi’s Pan-European Manifesto, other efforts to unify Europe also sought to defend and strengthen Europe’s freedom against various tyrannies such as the Soviet and later the National Socialist dictatorships.

In The Decline of the West, Spengler specifically contrasted democracy with the concept of culture and described it as a typical political crisis phenomenon of civilisation.

According to Spengler, democracy – as seen by the great political philosophers of antiquity, Plato and Aristotle, is an unstable-transitional political form that gradually transforms itself into various kinds of ‘Caesarisms’—the unlimited rule of certain oligarchs of the ruling political-economic complex.

Looking at the processes of modern European politics, Spengler emphasised the role of propaganda, i.e. the press, in a prominent place: according to him, this is the army with the help of which the democratic parties determine ‘what is the truth’ and what the ‘democratic’ mass should believe. The press—as in Soviet totalitarianism or in the later Third Reich—is also not free in democracies as the objectivity of communication is questionable.

The German philosopher had a very similar opinion about the constant sea of stimulus and advertising of the modern metropolis, one of the most characteristic features of modern industrial civilisation, and also of the technical apparatus of modern European cities. This influences ‘free’ individuals in the specified directions, who in the final state of civilization are actually under the strict control of the ‘guardian state’ of Tocqueville, (compare to the programme of ‘the complete digitisation of the world’) where the possibilities of free opinion formation and thinking are constantly manipulated and limited. As he writes:

‘Formerly a man did not dare to think freely. Now he dares, but cannot; his will to think is only a willingness to think to order, and this is what he feels as his liberty.’[4]

Among Spengler’s analyses and ideas about the ‘end of history’ and cyclic nature of culture and civilisation, of which are related to the current situation of Europe—in addition to its speculative aspects—we can still find plausible and adequate elements. Although, of course, no thinker can provide a perfectly accurate description of state and society or predict processes with complete precision, in the light of the historical experiences of the past and present, Spengler correctly pointed out that the naïve optimism of the Enlightenment, Condorcet’s ‘rational society’ and the idea of linear progress are hardly sustainable ideas.

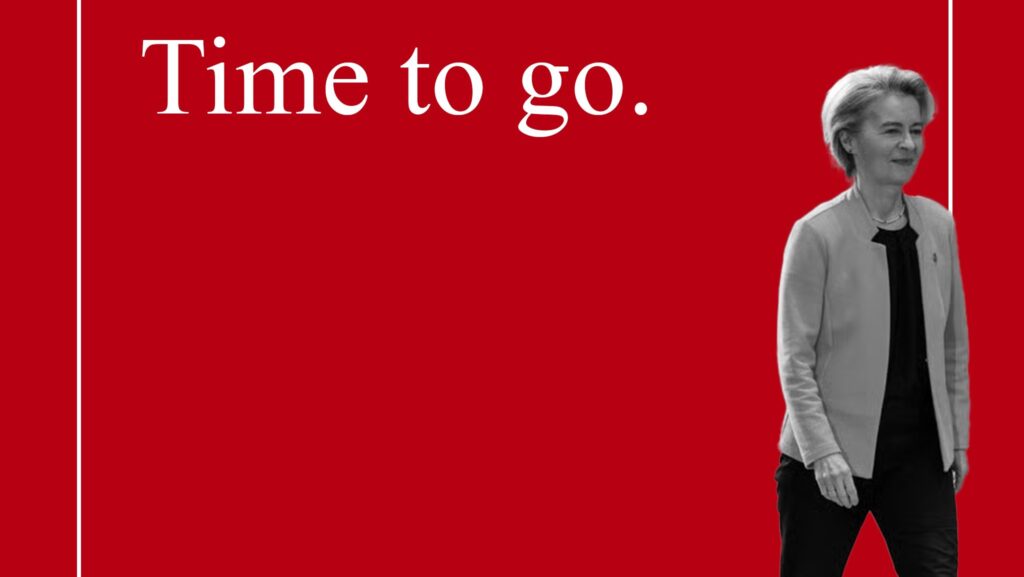

Europe’s contemporary society, the current system and operation of the European Union, its political, social and more deeper tensions—affecting the whole of human existence—all prove that the still popular phrase ‘progress’ is losing its catchword character just as more and more people become disillusioned with the ‘big projects of globalism.’ Today, the question is not primarily whether a united Europe can act as a great power against the great powers outside Europe, as Count Kalergi hoped a century ago. He wrote: ‘If Pan-Europe wins, then the way is clear for the solution of all social and cultural issues.’[5] The question is today, much more is whether something from the traditional values of European culture can be preserved and saved for the second half of the 21st century against waves of cultural decline.

[1] The first was published four years before: in 1918 – the last year of The Great War – which considerably shaped the politics of West in the 20th century.

[2] Richard N. Coudenhove-Kalergi, Páneurópai kiáltvány (1924), Grotius, http://www.grotius.hu/doc/pub/FXSWNI/2013-05-03_coudenhove-kalergi_paneuropai-kialtvany.pdf, accessed 30 Jan. 2023.

[3] Oswald Spengler, The Decline of The West, Volume I., New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1926, 106.

[4] Oswald Spengler, The Decline of The West, Volume II, London, George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1926, 463.

[5] Coudenhove-Kalergi, Páneurópai kiáltvány