In the modern world, the concept of authority has undoubtedly fallen into crisis. This phenomenon is no abstract theory but a palpable reality of our daily lives: it manifests in schools, where disrespect toward teachers occasionally escalates to physical violence; in families, where the bonds of generational hierarchy have loosened; and above all, in political life, where a significant portion of citizens can only relate to the state and its representatives with contempt or deep disillusionment.

The general disposition of the present world is such that it offers little real opportunity for finding meaning in life. A higher cohesion that would organize the social body into an ordered whole—one oriented toward some meaningful purpose beyond the individual’s existential ‘well-being’—is barely, if at all, visible. Under the present circumstances, relative discipline is either mechanical—that is, directed at the tool of work, the machine itself—or it stems from the fear of being fired and/or the hope of material gain, and the satisfaction found therein, which the so-called ‘consumer mentality’ attempts to establish as life’s sole purpose and meaning.

In this atmosphere, a pervasive and boundless individualism reigns, where everyone considers themselves the final arbiter, and where the proliferation of resonant opinions replaces genuine knowledge. In the world described by Guy Debord as the ‘society of the spectacle’, the void left by true authority is filled by ‘influencers’ who owe their success not to their achievements but to their number of followers.

The question arises: is all this merely a transient social disturbance, a symptom of a passing era, or is it the consequence of a much deeper philosophical shift encoded in the very foundations of modernity? To answer this, it is not enough to analyse the symptoms of the present; we must examine the intellectual framework that made this crisis possible—that is, the central myth the modern age has constructed about itself: the idea of ‘historical development’.

‘Is all this merely a transient social disturbance, a symptom of a passing era, or is it the consequence of a much deeper philosophical shift encoded in the very foundations of modernity?’

The idea of progress—the notion that history represents the inevitable, unidirectional advancement of humanity from an initial state of unfreedom toward a final, ideal, power-free liberty—is a cornerstone of modern thought. This narrative, though often expressed in a materialist form, is in fact the secularized and distorted heir of Christian soteriology. In the 20th century, the Russian religious philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev perhaps most brilliantly illuminated that the modern, linear concept of progress is not a product of science or reason at all, but a secularized version of Judeo–Christian eschatology.

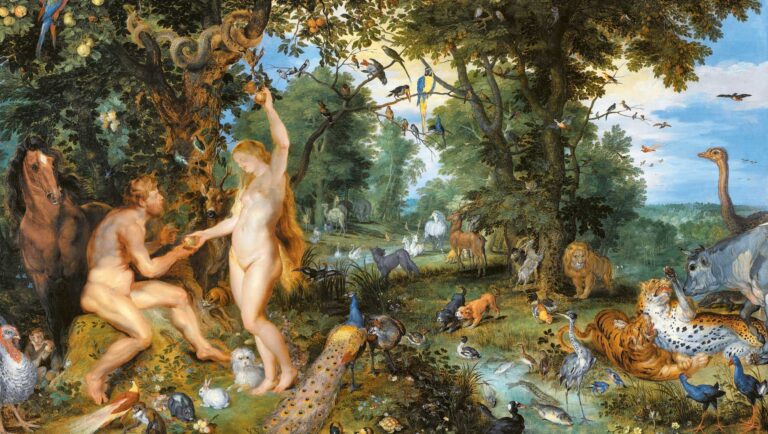

This linear model, in fact, originates in Christian salvation history; yet modern thought, while abandoning God and the otherworldly goal, retained the structure itself: the Fall of Man was replaced by ‘feudal oppression’ or ‘ignorance’, Redemption by ‘revolution’ or ‘scientific enlightenment’, and the Kingdom of God by the communist or liberal-democratic utopia. Berdyaev reveals not only the political consequences of the belief in progress but also the theological origins of the intellectual structure itself, exposing its secularized yet still faith-based nature.

And if he is correct—if the idea of progress is not the product of the modern, rational, and ‘scientific’ mind but a secularized theological construct—then modernity cannot, in fact, be separated from Christianity. It should rather be seen as its own ‘Christian heresy,’ or even more, as an inverted Christian paradigm of salvation history that has turned into a self-negating and self-consuming force.1

However, while the Christian worldview interpreted history as a divine drama between Creation and the Last Judgment, in which fallen human nature could only transcend itself through a transcendent intervention—the grace of God—the modern ideology of progress removed the concepts of Original Sin and transcendence. What remained was a boundless human optimism: the belief that humanity, merely through its own rationality, science, and institutions, is capable of creating an earthly paradise.

This essay argues that the modern crisis of authority stems directly from this progressive myth. It seeks to demonstrate how an egalitarian utopia—rejecting transcendent points of reference and natural hierarchies—has necessarily led to the destruction of genuine authority and produced an illusory order in which the democratic promise of popular sovereignty conceals a new and more pervasive form of power than any before. First, we will examine the concept of authority within the traditional order that preceded the ‘Enlightenment’; then, we will turn to a critique of the modern ideologies that dismantled it, before finally outlining the contours of the disenchanted, ‘post-historical’ condition of the present age.

The Apostles of Progress: Pinker, Fukuyama, and the Last Faith of Modernity

Of course, ‘progress’ still has its defenders today. However rare explicit progressivism may now be—as a kind of openly professed faith—buzzwords such as ‘innovation’ continue to carry overwhelmingly positive connotations, while the term ‘conservative’ is often associated with meanings such as ‘backward’ or ‘unimaginative.’ The ideology of ‘inevitable progress’ is still propagated by many widely read authors in various forms—sometimes openly, sometimes covertly, and often in such subtle ways that the reader scarcely perceives what is at stake.

From among the most influential contemporary defenders of progress, Steven Pinker stands out. According to him, any rejection of the achievements of the ‘Enlightenment’ amounts not only to a denial of fact but to a renunciation of common sense itself.2 Standing on the ‘solid ground’ of data and evidence, Pinker argues that the combined forces of reason, science, and humanism have measurably—and indisputably—improved the condition of human life. As he puts it:

‘Life before the Enlightenment was darkened by famine, plagues, superstition, childbed and infant mortality, marauding knights, sadistic torture-executions, slavery, witch hunts, and genocidal crusades, conquests, and religious wars.’3

Or elsewhere:

‘Our inability to prophesy is not, of course, a license to ignore the facts. An improvement in some measure of human well-being suggests that, overall, more things have pushed in the right direction than in the wrong direction. Whether we should expect progress to continue depends on whether we know what those forces are and how long they will remain in place. That will vary from trend to trend. Some may turn out to be like Moore’s Law (the number of transistors per computer chip doubles every two years) and give grounds for confidence (though not certainty) that the fruits of human ingenuity will accumulate and progress will continue. Some may be like the stock market and foretell short-term fluctuations but long-term gains.’4

Steven Pinker’s chapter on ‘Progressophobia’ in Enlightenment Now unwittingly provides the most eloquent proof of our essay’s central thesis. Pinker diagnoses modern pessimism towards the facts of progress as simply a cognitive error and a result of the media’s negative bias.

Although these superficial observations are valid on their own level, they ignore the real problem: Pinker psychologizes a deep metaphysical crisis. ‘Progressophobia’ is not an irrational fear but a justified existential anxiety, the soul’s instinctive protest against a spiritually hollowed-out world. The intellectual ‘prophets of doom’ whom Pinker mockingly lists—Nietzsche, Heidegger, Adorno, Foucault—were in fact the most clear-sighted diagnosticians of the age, who recognized the moral and spiritual decline hidden behind material development.

‘Pinker’s proposed solution…reveals in its purest form the fundamental error of modernity: the triumph of the reign of quantity…over quality’

Pinker’s proposed solution—mere calculation, this ‘morally enlightened’ method—reveals in its purest form the fundamental error of modernity: the triumph of the reign of quantity (René Guénon) over quality. This perspective is incapable of measuring the loss of sanctity, authority, and meaning. The ‘Optimism Gap’ he describes—where an individual sees their own life as good but the world as a whole as bad—is not a paradox but the perfect symptom of the modern condition: the diagnosis of a person who has retreated into the private sphere but is disconnected from a common, meaningful order, a spiritually homeless human being. Thus, Pinker’s work, written to refute the critics of modernity, becomes their chief evidence.

However, Pinker’s optimism is not undisputed even within contemporary thought. While he summarizes the past achievements of progress, Yuval Noah Harari, another popular author of grand historical narratives—more famous worldwide than Pinker—paints a much more ambivalent picture.

Harari likewise acknowledges the unprecedented expansion of human power—from the cognitive revolution to modern scientific breakthroughs—yet he persistently raises the question: has this power brought greater happiness? In the pages of Sapiens and Homo Deus, a future unfolds in which technological development may not culminate in the realization of freedom, but rather in the mass redundancy of human beings or the rise of a new bio-technological caste system—a trajectory toward an endgame that could transcend the liberal democracy once proclaimed by Francis Fukuyama as the ‘end of history.’

Fukuyama—perhaps the most well-known representative of the classical, ‘enlightened’ idea of progress at the turn of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—gave this narrative its clearest political telos. Drawing on Hegelian philosophy, Fukuyama argued that the engine of history is the ‘struggle for recognition’. For him, liberal democracy represents the end of history because it is the only system that provides universal and reciprocal recognition to all citizens, thereby satisfying the deepest desire of human nature.

Yet, unlike Pinker’s naïve optimism, Fukuyama is no fanatical modernist. A substantial part of his work is devoted to diagnosing the internal tensions of modern liberalism. In Trust and The Great Disruption, he identifies social capital—strong families, civic communities, and culturally embedded trust, all highly valued by conservatives—as a precondition for a successful democracy. Similarly, in Our Posthuman Future, he warns of the dangers that biotechnology poses to human nature; and more recently, he has spoken against the identity politics that fragment contemporary society.

Fukuyama’s work is perhaps the most intelligent attempt to save modernity from itself. Yet, in the end, he seeks to rationally furnish a house whose very foundations have been undermined by the loss of its transcendental anchor. His sophisticated liberalism is thus not a refutation but rather the most eloquent expression of the inherent limitations of the modern project.

Fukuyama’s model embodies a central error of modernity when it replaces the traditional, qualitative, and hierarchical concept of dignity (which was tied to virtue and one’s place in a transcendent order) with an abstract, legal, and quantitative recognition.

‘By Hegel’s account, the desire to be recognized as a human being with dignity drove man, at the beginning of history, into a bloody battle to the death for prestige. The outcome of this battle was a division of human society into a class of masters, who were willing to risk their lives, and a class of slaves, who gave in to their natural fear of death. But the relationship of lordship and bondage—which took a wide variety of forms in all the unequal, aristocratic societies that characterized the greater part of human history—ultimately failed to satisfy the desire for recognition of either the masters or the slaves. The slave, of course, was not acknowledged as a human being in any way whatsoever. But the recognition enjoyed by the master was deficient as well, because he was not recognized by other masters, but by slaves whose humanity was as yet incomplete. Dissatisfaction with the flawed recognition available in aristocratic societies constituted a “contradiction” that engendered further stages of history.

Hegel believed that the “contradiction” inherent in the relationship of lordship and bondage was finally overcome as a result of the French and—one would have to add—American revolutions. These democratic revolutions abolished the distinction between master and slave by making the former slaves their own masters and by establishing the principles of popular sovereignty and the rule of law. The inherently unequal recognition of masters and slaves was replaced by universal and reciprocal recognition, where every citizen recognizes the dignity and humanity of every other citizen, and where that dignity is recognized in turn by the state through the granting of rights.’5

By recognizing everyone equally as citizens, the system in fact recognizes no one’s particular quality; it replaces the vertical desire for recognition once directed toward God with a shallow, horizontal validation. This process leads not to fulfilment but to the hollowed-out, aimless condition of the ‘last man’ foreseen by Nietzsche—an individual concerned only with comfort and security. Fukuyama’s model, therefore, is not the consummation of history but rather a depiction of its confinement within a spiritually vacuous, administrative order: the triumph of nihilism in the name of freedom.

Harari’s vision attacks this very premise. According to him, 21st-century biotechnology and artificial intelligence could create not just new political systems, but entirely new human species. The struggle for recognition is replaced by the desire for immortality, happiness, and godlike abilities. This projects a new, post-human struggle between the technologically enhanced Homo Deus and the obsolete Homo Sapiens. In such a world, liberal democracy—built on the equality and universal rights of humans—loses its meaning. Harari’s vision, therefore, is what comes after the ‘end of history’: an era in which the satisfied ‘last man’ described by Fukuyama is not the endpoint of development, but merely a transitional phase before a complete biological and social transformation.

‘The struggle for recognition is replaced by the desire for immortality, happiness, and godlike abilities’

However, although Harari appears to question and even reject the notion of progress, in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind he ultimately revives the classical topoi of the progress narrative. He depicts human history as a linear sequence of three accelerating revolutions—the Cognitive, the Agricultural, and the Scientific—culminating in a clearly defined endpoint: transhumanism. While he moves beyond the traditional ‘humanist’ image of progress, his perspective nevertheless devalues and caricatures the past. He reduces premodern humanity to an animalistic level: ‘The most important thing to know about prehistoric humans is that they were insignificant animals.’6

Likewise, he simplifies the complex social and cultural realities of premodern life—much like his predecessors Voltaire and Condorcet—through demagogic and distorting imagery: ‘In modern affluent societies it is customary to take a shower and change your clothes every day. Medieval peasants went without washing for months on end and hardly ever changed their clothes. The very thought of living like that, filthy and reeking to the bone, is abhorrent to us.’7

In Harari’s work, this rhetoric clearly serves to render the achievements of technical civilization both inevitable and exclusive—the only conceivable trajectory of history—even as he paints a deliberately ambivalent and at times ominous picture of its outcome. At the same time, any sympathy for the past is made to appear irrational. Harari—much like the eighteenth-century materialist and deist representatives of the ‘Enlightenment,’ such as Baron d’Holbach,8 Denis Diderot,9 and Voltaire—subjects reality to a crude reductionism when he writes: ‘How exactly did Armand Peugeot, the man, create Peugeot, the company? In much the same way that priests and sorcerers have created gods and demons throughout history, and in which thousands of French curés were still creating Christ’s body every Sunday in the parish churches.’10

This passage perfectly exemplifies the unreflective materialist attitude that collapses transcendent reality and economic entity into the same ‘fictitious’ category—without, for a moment, acknowledging the constructed and ‘mental’ character of its own materialist worldview. The analysis of history thus becomes an instrument of ideology: a means of justifying the inevitability and desirability of globalization and technological utopia.

The position of the present essay, however, is more radical than all these approaches. It does not merely question the outcome of progress (like Harari) or its political endpoint (like Fukuyama), but attacks the very premise celebrated by Pinker. The problem is not whether progress has material benefits—it would be foolish to deny them—but that the concept of progress has forced upon us a materialist and quantitative worldview that is incapable of measuring, or even perceiving, what was lost in the process. This paper argues that the price paid for techno-economic development was the abolition of metaphysical certainty, transcendent meaning, and genuine, organic authority. Our diagnosis, therefore, is not that progress is heading in the wrong direction, but that ‘progress’ itself is the wrong compass.

‘[It] is not that progress is heading in the wrong direction, but that “progress” itself is the wrong compass’

This flawed compass—this mindset that reduces the world, from nature to man, to a mere measurable and exploitable resource—is what Martin Heidegger described as the essence of modern technology: the Enframing (Gestell). The Enframing is a vast, all-encompassing framework that ‘challenges’ and ‘orders’ the whole of reality as a ‘standing-reserve’. Within this system, everything—the river as potential energy, the forest as timber, the earth as mineral deposits, and man as ‘human resources’—exists from a single standpoint: as available, usable, optimizable stock (Bestand).11

The Enframing does not simply denote machines but rather a global logic that regards all things and beings as ‘standing-reserve,’ as objects to be exploited. According to Heidegger, the forgetting of Being as the ultimate horizon of meaning, in favour of mere beings—things, facts, and data—is the fundamental dynamic of Western history, which has reached its consummation in our own age.12

Pinker’s data-driven world is, in truth, a manifesto for the triumph of the Enframing; Harari’s dystopian vision is its logical consummation, in which man himself becomes data to be processed by the system—or a superfluous raw material. Within such a framework, authority—grounded not in utility but in the incalculable, the sacred, the commanding of respect—cannot exist by definition. In the logic of the Enframing, authority, too, becomes nothing more than a resource for the efficient operation of the socio-political machinery.

- ‘This idea has ancient religious-messianic roots. It is the old Judaic idea of the messianic solution of history, of the advent of a Messiah who will solve the earthly destiny of Israel and, with it, that of all peoples. It is the ancient belief in the realization, sooner or later, of the Kingdom of God—the reign of perfection, truth, and justice. This messianic and millenarian idea becomes secularized in the doctrine of progress; that is, it loses its manifestly religious character and assumes one that is worldly and even anti-religious. It is not an exaggeration to say that for many people the doctrine of progress was a religion—that the religion of progress in the nineteenth century was professed by many who had fallen away from Christianity.’ (Nikolai Berdyaev, The Meaning of History, trans George Reavey, London, The Centenary Press, Geoffrey Bles, 1936, pp. 186–87.) ↩︎

- Steven Pinker is a Canadian American cognitive psychologist, professor at Harvard University, and one of the most influential figures in 21st-century Anglo–Saxon intellectual life. While Yuval Noah Harari’s historical bestsellers are perhaps the most globally recognized examples of contemporary ‘popular science’, Pinker’s work holds particular significance within the Anglo–Saxon world. He is arguably the foremost scientific advocate—and indeed the archetype—of the modern, Enlightenment-based progress narrative.

In his two major works, The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011) and Enlightenment Now (2018), Pinker argues, drawing on vast statistical databases, that the human condition—from the decline of violence to the rise in life expectancy and material well-being—has dramatically and measurably improved in recent centuries. According to Pinker, this success is clearly attributable to the ideals of the Enlightenment: reason, science, and humanism.

He is mentioned first among the modern defenders of progress because his work embodies the purest, most optimistic, and most militant expression of the materialist, data-driven worldview that this essay seeks to critique. ↩︎ - Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress, New York, Viking, 2018, e-book, ch. 21. ↩︎

- Ibid, ch. 4. ↩︎

- Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, New York, Free Press, 1992, pp. 17–18. ↩︎

- Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Toronto, Signal / McClelland & Stewart, 2014, p. 12. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 388. ↩︎

- Baron d’Holbach’s Parisian salon was the centre of radical, atheist thought. His main work, The System of Nature (Système de la Nature, 1770), is the most important atheist text of the French Enlightenment, a kind of ‘atheist Bible’. In it, he argues on a relentlessly materialist basis that there is no God; religion stems from ignorance and fear; the human soul is mortal and a product of the brain’s functioning; and the basis of morality is not divine command but social utility and the pursuit of individual happiness. ↩︎

- As the editor-in-chief of the Encyclopédie, Diderot, hiding behind cautious phrasing, systematically undermined the authority of religious dogmas by favoring scientific and rational explanations. His famous novel, The Nun (La Religieuse), portrays monastic life as a hell of coercion, psychological terror, and repressed sexuality, which is a powerful anti-clerical statement. ↩︎

- Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, p. 37. ↩︎

- ‘The hydroelectric plant is not built into the Rhine River as was the old wooden bridge that joined bank with bank for hundreds of years. Rather the river is dammed up into the power plant. What the river is now, namely, a water power supplier, derives from out of the essence of the power station. In order that we may even remotely consider the monstrousness that reigns here, let us ponder for a moment the contrast that speaks out of the two titles, “The Rhine” as dammed up into the power works, and “The Rhine” as uttered out of the art work, in Hölderlin’s hymn by that name. But, it will be replied, the Rhine is still a river in the landscape, is it not? Perhaps. But how? In no other way than as an object on call for inspection by a tour group ordered there by the vacation industry.’ (Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, trans William Lovitt, Harper & Row, 1977, p. 16.) ↩︎

- ‘This question has today been forgotten…For manifestly you have long been aware of what you mean when you use the expression “being”. We, however, who used to think we understood it, have now become perplexed…Our aim in the following treatise is to work out the question of the meaning of Being and to do so concretely.’ (Heidegger, Being and Time, trans John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson, Blackwell Publishers, 1962, p. 21.) ↩︎

Related articles: