László Ottlik (1895–1945) was one of the defining figures of Hungarian political thought between the two world wars. His oeuvre covered not only political science, but also sociology, aesthetics, jurisprudence and political journalism. He was concerned with issues like the philosophical meaning of the term ‘politics’, the concept of majority and minority, the relationship between mass society and modernity, the question of the origin of sovereignty and of state power, as well as a specific interpretation of democracy, a critique of liberalism, or the new types of dictatorship. In fact, he spoke about all the questions of his time that had only a loose relationship with politics: such was the English labour question, American capitalism, German legal philosophy, Hungary’s foreign policy, or the development of international power relations. Despite the large body of work he left behind, there is very little awareness of him in today’s Hungarian culture. (Géza Ottlik, Hungarian writer much better known than him, was his cousin.)

For this reason, the enterprise of József Szabadfalvi is to be welcomed, since from the early 2000s, he began to systematically publish articles on Ottlik’s oeuvre, and during the course of last few year, he also published a short monograph.[1] As Szabadfalvi also points out: from the point of view of the Hungarian tradition of political thought, perhaps Ottlik’s greatest merit is that he was among the first political scientists who tried to open up the 19th century approach of political science (represented by such figures as Gyula Kautz, Ignácz Kuncz, Győző Concha), creating a new one.

It can be argued that, as result of the interplay of several different factors, political philosophy that is clearly separated from legal philosophy could not really take root in Hungary either in the Renaissance or in the 18th–19th centuries. Outstanding experiments such as certain writings of Count István Széchenyi or Aurél Dessewffy, the ‘Ruling ideas’ of Baron Eötvös,[2] or some excellent political essays by Zsigmond Kemény did not really enter the scientific circulation and remained isolated experiments. Ottlik can be considered

one of the first Hungarian practitioners of political philosophical thought, who can be integrated into the Western traditions of political thinking.

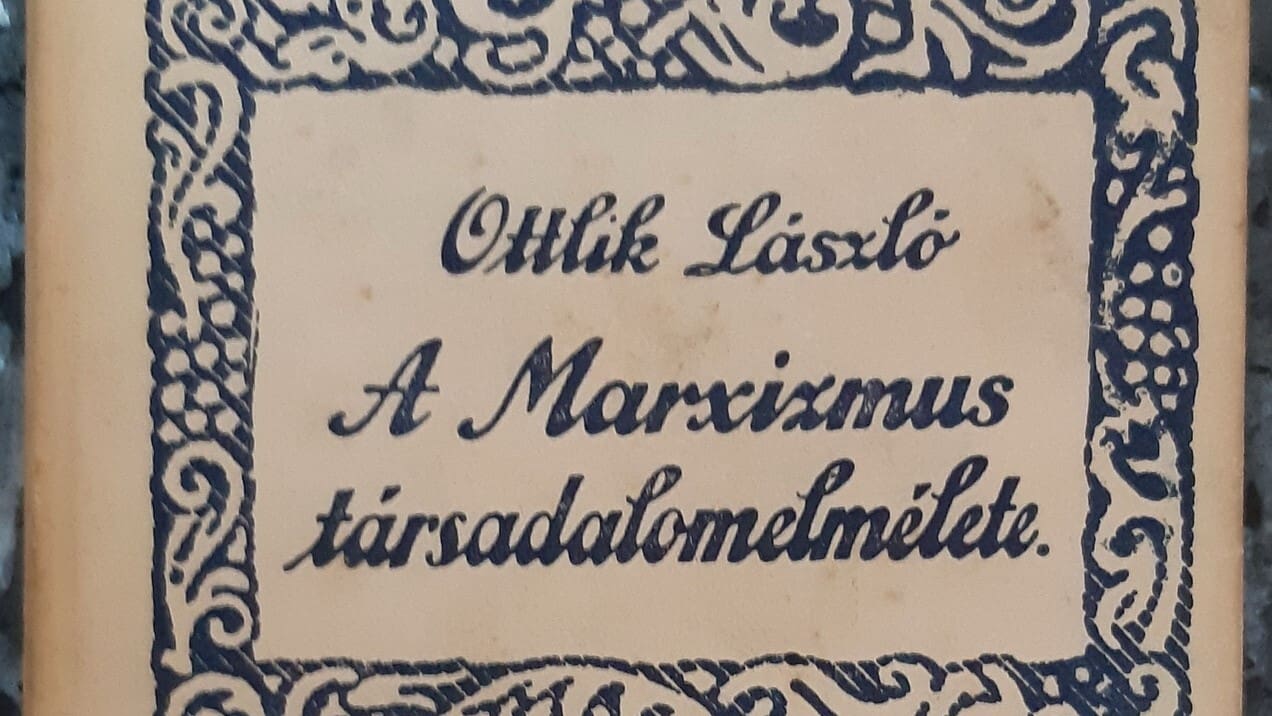

Ottlik in Hungary is among the first who attempted (within a university framework) to inculcate a way of speaking that also carries on a dialogue with the most important political authors of his time. His biographer, József Szabadfalvi, calls László Ottlik a conservative social scientist. Ottlik himself did not use the term ‘conservative’ and the name ‘conservatism’ to characterize his ideological position—rather, the term ‘conservative’ appears for Ottlik in the literal sense of ‘preservation’ and with no implications of a definite political ideology or worldview. It is obvious from his references that the development of his Weltanschauung was strongly influenced by modern natural scientific thinking: positivism and Darwinism play an important role in the formulations of the thought of the young Ottlik. However, there is also the strong reference to the authority of the ancestors instead of the ‘authority’ of ‘Enlightened Reason’ in an early work written against Marxism,[3] which practically opened his career as a social scientist; the work is undoubtedly an element that can be related to conservative thought.

As he formulated:

‘[All] authority in knowledge, experience, and age are the elders: the ancestors, so the authority of the past. God is also “father”; his authority is the very first ancestor: the authority of a being older than all existence. The past…is an integral part of the present: what is memory in the individual consciousness, is tradition in the social consciousness.’[4]

It seems obvious: like many thinkers characterized as ‘conservative’ by critics, the literature, or his reviewers, Ottlik also did not think that ‘conservatism’ is a political ideology similar to socialism or liberalism, which had dogmatically graspable and descriptive ‘articles of faith.’ At the same time, he is definitely a conservative as he criticizes the ideas that developed in the wake of the Enlightenment.

Ottlik thoroughly debates such notions as ‘necessary progress’ associated with the material development of human civilization, materialistic atheism, rational epistemological optimism, forced egalitarianism, or the belief in the constantly ‘developing’ human nature, or the economic ‘redemption’ of society. Ottlik’s knowledge and extraordinary grounding are immediately apparent even from the references in his writings. Among the authors he likes to quote we can find Oswald Spengler, Robert Michels, Vilfredo Pareto, Eduard Spranger, Carl Schmitt, Max Weber, Max Scheler and Arnold Toynbee.

As Hungarian political scientist Ervin Csizmadia puts it in his essay on the political science of the ‘Horthy regime’: ‘[I]t’s enough if I refer again to, for example, László Ottlik’s political “debate theory”, in which he tries to characterize the concept of political public opinion, and characterizes the “dialectic” of party struggles, or rather—well ahead of Dahl—the concept of polyarchy.’[5] Ottlik’s works describing the political systems of the time—believed to be the most lasting and could hold the most important messages for the profession—can be found in the following longer studies and books: Dictatorship and Democracy (1929), Parliamentarianism and Dictatorship (1932), The History of Political Systems. The Middle Ages and the Modern Age until the World War (1940), The Political Systems (1939) and Introduction to Politics (1942).

In his works related to political systems, he described and interpreted the history of English, American, French, Italian, German and Russian political development, in terms of methodology, in some places using more analytical political scientific approaches, in others with essayistic contributions. His ‘classical’ categorization of state forms also revives the basic state theoretical ideas of Greek philosophy, going back to Plato’s and Aristotle’s state forms. In order to establish his conclusions, the political scientist separated and distinguished the concepts of ‘form of government’ and ‘form of state’: according to him, only two forms of government are possible: monarchy or oligarchy. The form of government is determined by who or on whose behalf the monarchical or oligarchic exercisers of power control and govern the state: if for one person, then the form of government is autocracy, if for the ‘best’ then aristocracy, if for the ‘great mass as sovereign’ it is a democracy. According to Ottlik, the different combinations of the two basic forms of government and the three forms of state have created extremely complicated combinations through the course of history, and in fact

we cannot talk about such ‘pure forms’ that would allow political systems to be classified according to the simplistic categories of ‘dictatorship’ or ‘democracy.’

Different attitudes may prevail in a given political system, and these may determine the purpose of the state, creating or even destroying the conditions for political freedom or justice.

As we can see: in contrast to state theories of the liberal contract theory tradition, represented by thinkers such as Locke, which make the enforcement of the abstract principle of ‘freedom’ (justice, good governance) dependent on the limitation of state power, for Ottlik, the possibility of ‘good order’ is hardly, or not at all, dependent on the form of the state. In his view, similarly to the Platonic-Aristotelian tradition, it is primarily the attitude of the ruler(s) that decisively influences the existence of the political good order. It should be noted, nevertheless, that Ottlik highly praised British parliamentarianism before the outbreak of the Second World War, although he did not consider the English ‘insular’ form suitable for ‘continental’ parliaments even then.

From the middle to the end of the 1930s, what brought his world view drew closer to the conservative-liberal position represented by Count Bethlen and his circle. This is definitely the case, for example, regarding his clearly favouring ‘free competitive capitalism’ in an article penned in 1931, where Ottlik attributes ‘the higher cultural and social development of humanity’ to capitalism.[6] His reference to the ‘classic English proverb’ that states ‘democracy is self-government’ can be linked to this approach when he called the essence of the ‘new Hungarian state ideal’ a ‘self-governing democracy’ in his essay ‘Pax Hungarica’ .[7] In his 1932 study titled ‘Parliamentarianism and Democracy’, he characterized British parliamentarianism as a ‘veritable high school of aristocratic governance in a good sense’: at that time, he believed that the line of English governance successfully detached itself from the political currents of the day. The British Parliament so fortunately combines the aristocratic and democratic principles that in it ‘the aristocracy of birth increasingly gives place to a purely intellectual and moral aristocracy, which, however, has preserved all the virtues and traditions of an old aristocracy of birth,’ he wrote. Like Tocqueville, Ottlik traced back the uniqueness of English development to the preserved independence of the English aristocracy against the growing centralization of state power in the early modern age. This is how, according to him, the institution of the British Parliament could become the balanced government body that ‘Unifies the advantages of aristocracy and democracy: it provides aristocratic governance on the broadest democratic basis.’[8]

[1] See József Szabadfalvi, Egy konzervatív állam és politikatudós. Ottlik László (1895–1945), Dialóg Campus-Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó, Budapest-Debrecen, 2019.

[2]See Baron József Eötvös: Influence of the Ruling Ideas of the 19th century on the State

[3] See László Ottlik: A marxizmus társadalomelmélete – Elméleti kritika és történelmi tanulságok. Franklin-Társulat, Budapest, 1922.

[4] Ottlik, A marxizmus társadalomelmélete, 54.

[5] Ervin Csizmadia, ‘A magyar politikatudomány tradíciói a két világháború között. Munkabeszámoló’, OTKA. http://real.mtak.hu/2695/1/69072_ZJ1.pdf. (acessed: 2023. 12. 13.)

[6] László Ottlik, ‘Kapitalizmus, szocializmus és világválság, Magyar Szemle, 1931 XIII/3. 201-209.

[7] László Ottlik, ‘Pax Hungarica’, Magyar Szemle, 1934. XXII/ 3. 289-299.

[8] László Ottlik, ‘Parlamentarizmus és demokrácia’, Magyar Szemle, 1932 XIV/4, 391.