This article was originally published in Vol. 5 No. 3 of our print edition.

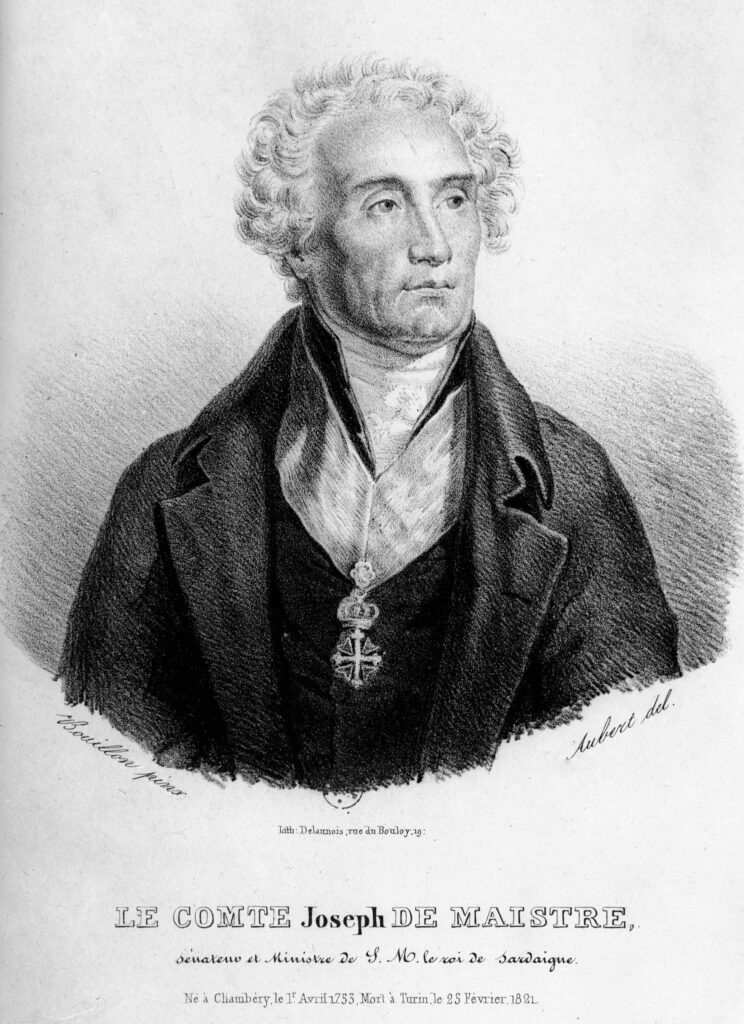

Joseph de Maistre (1753–1821) is a characteristic representative of the Catholic theological view of man. In his works, this perspective is interwoven with his critique of the French Revolution and of republicanism, as strikingly exemplified by his scattered but recurring critique of America. Fundamentally, by the end of the eighteenth century, the New World had failed to win over the natural scientists of the Enlightenment. According to the most common observations, it offered too wild and dismal a picture—whether of its people or its wildlife. Belief in the possibility of full civilizability seemed to diminish, with most attributing this to America having a harsher climate than Europe’s. Tellingly, however, de Maistre does not trace his deeply pessimistic view of the New World entirely back to this cause. Rather, he concludes that the continent’s savage peoples suffer from an incurable state of moral decline, brought about by a grievous crime committed long ago by some unknown tribal chief.1

When de Maistre takes a stand and denies the prosperity of the New World, he does so for several reasons—of which the era’s prevailing atmosphere of scientific scepticism towards America is the least interesting. On the one hand, he seizes the opportunity to undermine the anthropological optimism of the philosophes. On the other hand, he links the American and French Revolutions in a tragic context: ‘After 15 years of peace, the American Revolution involved France anew in a war the consequences of which all human wisdom could not foresee. The peace was signed in 1782 [1783 Treaty of Paris]; seven years later, the Revolution began. It still continues, and it has cost France perhaps 3 million men so far.’2

As for his critique of anthropological optimism, de Maistre’s chief target was Jean-Jacques Rousseau; in this spirit, his reflections on the American natives are in truth only a superficial pretext. These peoples serve him well as a convenient refutation of the ideal of the ‘noble savage’.3 De Maistre regarded Rousseau’s attempts to describe man in a ‘state of nature’ as absurd, insisting instead that man is by nature a social being. The foundations of his argument lie in Greek mythology and the Christian biblical tradition, drawing on figures such as Homer and Saint Paul.4 It is important to stress that behind de Maistre’s remarks on America, there lies a constant concern with defending Europe’s natural social order. As Joseph Eaton has pointed out, de Maistre had no wish to present a coherent picture incorporating all of his contemporaries’ knowledge of the New World. As a widely read and sophisticated thinker, he certainly could have done so, but his interests and aims pointed far more toward safeguarding the Old World against the revolutionary tide. For this reason, he deploys the supposed barbarism of the American natives primarily as a weapon, rather than as the subject of genuine scientific inquiry.5 Moreover, the behaviour of the ‘savages’—if not entirely misinterpreted, then certainly at least understood superficially—fitted conveniently into de Maistre’s doctrine of social and political revelation through sin and punishment. Original sin pervades every human society, and any human community that had not reached the European model of civilization, he suggested, must also have committed some unknown ‘second original sin’. Thus, de Maistre imagined that, at some point in the past, an unnamed tribal chief’s grievous offence had cast the natives back into a ‘de-socialized’ state of confusion and violence.

Yet this is not a fully developed sociology, but rather the clever stroke of a political pamphleteer, in which the ‘second original sin’ of the overseas barbarians emerges as an allegory of the French Revolution. European societies, despite—or rather under the moral weight of—the first original sin, had built up Christian civilization. But the revolution that began in 1789 was itself a kind of original sin. Read in this light, de Maistre’s conclusion is clear: France, collapsing radically in the realm of public morals (like every European country in which revolution held sway), had engendered a new barbarism, in which violence and unrestrained suffering replaced natural society. ‘It suffices for me,’ writes de Maistre, ‘to indicate the falsity of the argument that the republic is victorious, therefore it will last. If it were absolutely necessary to prophesy, I would rather say that war keeps it alive; therefore, peace will kill it.’6

According to this view, the republic born in blood would eventually be brought to an end by a new era, one bearing the name of peace. De Maistre undoubtedly believed that the turbulent period of revolution would be followed by a purer world; indeed, it was in this context that he made his famous proposals regarding the qualities of a true counter-revolution. He accepted that humankind was capable of progress and improvement, and in this respect, his outlook shows affinities with Rousseau. This, however, is less surprising, for among scholars of de Maistre it has by now become a certainty that he was a secret admirer as well as a fierce rival of the Genevan.7 In Rousseau, he saw above all a metaphysical philosopher who had lost his way—one who, by the end of his life, had mistaken a wrong path for the right one.8

Humans or Celestial Bodies?

De Maistre, bearing the undeniable influence of Rousseau among others, maintained a constant interest in certain aspects of anthropology. Although his superficial and fragmentary critique of America was excessively self-serving, it nevertheless fitted into the polemical intellectual climate of the 1790s.

In a short, unpublished piece—regarded as the last of de Maistre’s works to be discovered—he grapples with serious dilemmas concerning the relationship between man and progressive science. The manuscript, ‘Essai sur les Planètes’ (‘Essay on the Planets’), was written in 1799 during his exile in Venice, after the French revolutionary troops had occupied Turin. In the city of the doges, de Maistre had no remunerative position.9 Despite its brevity, the essay is deeply critical in tone and offers noteworthy insights. It becomes apparent very quickly that his intention is not to discuss astronomy as such, but rather the image of man in modern natural science and philosophy. The key sentence appears right at the outset:

‘Among the ridiculous traits that characterize modern philosophy, one can distinguish its contradictions on the dignity of man. When it is a question of arming pride against traditional truths, nothing is above our grandeur: man is made for the truth; he must look for it by his own strengths; no authority has the right to hamper his thought. They give us the most pompous and detailed account of his knowledge and his discoveries; they make a God of him. But if, from the true grandeur of man, one wants to draw arguments about his future destiny, they quickly change the tune; they lower man by all possible means. They speak only of his ignorance, his vices, his weakness, and his ridiculousness; he is an animal, he is a worm.’ 10

The essay develops this guiding idea further under the aegis of classical and Christian reasoning, with claims such as ‘everything has been created by and for intelligence’, and ‘the world is only a system of invisible things manifested visibly’. Although fragmentary, the text—while its conclusions belong more to the genre of apologetics—can nonetheless be seen, in terms of content, as an early critique of scientism. According to de Maistre, the enlightened representatives of natural science hold mutually contradictory conceptions of humanity. They deify man, viewing him as the crown of existence, a being created for truth, whose freedom of thought no power has the right to suppress. And yet, paradoxically, they also look down on him, for they do not believe he is capable of complete knowledge. Scientists employ modern astronomy as their instrument, pointing to the infinitude and unknowability of the universe as proof. In comparison with these incomprehensible infinities, man is reduced to a mere unknown point—or, if one prefers, a worm.

‘The necessity and significance of sacrifice…lies in voluntariness’

Although de Maistre does not name the scientists he criticizes, there are clues as to whom he had in mind. One candidate is the materialist naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1707–1788), to whom he briefly refers in De l’état de nature (On the State of Nature): ‘Rousseau treated politics like Buffon treated physics.’11 De Maistre undoubtedly disliked him. The antipathy is well-founded if we consider Buffon’s encyclopaedic collection Histoire naturelle (Natural History), in which he rejects the idea of man’s central place in nature. In Buffon’s view, man essentially belongs among the animals; he does not rule over nature but merely exists within it as a participant.12

Whomever precisely de Maistre had in mind, his stance amounted—save for a few exceptions—to a rejection of the entire progressive scientific discourse of the 18th century. Yet the Enlightenment’s counterproductive, overly detailed conception of man was broad enough to allow for polemics even among the philosophes themselves. The radical materialist Julien Offray de La Mettrie and his ‘man-machine’ theory, for example, drew vehement criticism from contemporaries, as did, to a lesser extent, the later writings of Rousseau. In de Maistre’s eyes, of course, such disputes among the philosophes were nothing more than ridiculous infighting—when set against the outcome, which culminated in the Revolution and its destructive effects.

The most important ideas of the ‘Essai sur les Planètes’ point rather toward the future. Above all, they show that de Maistre understood the problem of unconditional trust in science. The Enlightenment persuaded man that he could rise to divine heights, question everything, and rely solely on his own reason—that his childhood was over. The scientific revolution established a strong sense of self-respect, which, with the political revolution, degenerated into arbitrariness. In the process, that which was most essential was lost: human dignity. It was above all as the defender of this that de Maistre raised his voice. The mentality of the philosophes—exalting man to the place of God, and at the same time debasing him among the reptiles in light of the universe’s infinity—remained an influential outlook even in the centuries that followed. One of its most expressive motifs can be found, for instance, in the phrase ‘pale blue dot’, or in the emphatic assertion that man is, in the end, nothing but stardust.

These late 20th-century observations likewise draw on the findings of astronomy. Their conclusions, however, incorporate critiques of anthropology, theology, and politics, conveying simplified world-view messages in an enigmatic fashion. In this way, an unofficial canon links the philosophe society of the Enlightenment with the most popular scientific authors of postmodernity, such as Carl Sagan, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and Richard Dawkins. Scientism—if we take this to mean the extension of the methods and assumptions of the natural sciences into the social sciences and, through them, into morality and public life—represents an important rupture in the history of European thought grounded in metaphysics. Its naturalist presupposition is that there exists only a single reality in the world, which can be known solely by immanent means, namely, physical perception and scientific methodology. Consistently bound up with this is therefore the desacralization of religion and the sacralization of science.13

‘Sacrifice is in fact adoration…which sanctifies both the individual and society’

De Maistre’s brief, unpublished essay of 1799 can, in fact, be regarded as one of the earliest critiques of scientism. The count was among those who—though they could not see the ultimate outcome with crystalline clarity (we must remember that de Maistre’s polemic primarily aimed at the liberal-minded bourgeoisie of his own age, while socialism and a politicized working class were products of later decades)—nonetheless, with something of a prophetic instinct, touched upon a very important and central problem. This was, simply put, nothing less than the dominance of the scientific perspective over human nature, and above all over human dignity itself.

The Universality of Sacrifice

It is a broadly accepted commonplace within anthropology and adjacent scientific disciplines that every society possesses a fundamental fabric encompassing its basic norms and forms of thought and behaviour. If we dig down to its deepest level, this fabric is revealed in the manifold diversity of sacred rites. According to de Maistre, what underlies all of these is the act of sacrifice.14 Sacrifice is at once the founding rite of society, and in later ages a commemorative act recalling that foundation. In de Maistre’s interpretation, its purity is manifested in two interconnected ways: first, in the crucifixion of Christ, which redeemed all humanity from its sins;15 and second, in the self-sacrifice of mortal men.16 The former, in its unrepeatable uniqueness, attains universality by extending to all peoples. The latter, repeatable in nature, acquires its universality in the founding or purification of particular societies.

The shed blood of Jesus Christ washed away the sins of the entire universe—a claim de Maistre does not intend as mere poetic exaggeration.17 If God, possessing the highest degree of reason, was capable of filling the Earth with beings who bear within themselves the spark of reason, then the same must hold true for other planets and the life forms presumed to dwell there. Yet as far as the planet of human beings is concerned, sacrifice takes different forms.

The work On Sacrifice is remarkable not only because it is among de Maistre’s most fully developed writings. In it, he undertakes nothing less than to identify the most fundamental, society-shaping rite of human civilizations. Why is it, precisely, that sacrifice—and more specifically, the offering of blood—provides the elementary cohesion of societies? He sought to answer this in three chapters. In the first, apologetics once again seems to come to the fore: ‘I cannot approve the impious maxim: It was human fear that first engendered the gods.’18 Every festival is rooted in the sacred and is joyful. People at once worship and praise the deities because they are gracious and all good things can be obtained from them, but they are also just, and in that respect, wrathful. They know that mortals are sinful, and accordingly, they must atone. The most effective means of propitiation, as Maistre puts it, is sacrifice.19

As the following two chapters also testify, only man is capable of this: ‘Animals received only a soul; we have been given both soul and spirit’, de Maistre asserts.20 Yet according to the testimony of history, men capable of sacrifice have practised the appeasement of the gods in ever more terrible ways. De Maistre devoted the second chapter of his work to examining this claim. Here, for the first time, there emerges an anthropological learning that had previously appeared mostly grafted onto political pamphlets, serving no other purpose than to attack the philosophes. The barbarism of the ‘savages’ of the Americas now appears as a more concrete justification than as the consequence of some primaeval sin committed by an unknown tribal chief. De Maistre presents past and contemporary societies with non-Christian civilizations as a whole as devotees of a misunderstood rite of sacrifice. These societies, by practising human sacrifice, had corrupted—and continue to corrupt—the sacred ritual.21 Alongside archaic peoples,22 he makes mention of the peoples of the Americas23 and of the Indians.24 In de Maistre’s reading, cruel sacrifice serves to equate the various cultures—all primitive in comparison with Christian Europe. Their societies are bound together by blood, or more precisely, by bloodshed. But a society that kills members of its own community in order to appease the gods is, in fact, sacrificing in error, and in doing so forfeits precisely the favourable destiny it hopes to achieve in the future. In de Maistre’s anthropology, human dignity held a place among the highest qualities; he took this into account both in shaping the ideal of a pure counter-revolution and in his writings criticizing early scientism. This is, in fact, what he upholds when he recalls the bloodthirsty rituals of human sacrifice among vanished and existing tribal societies. The necessity and significance of sacrifice, he believed, lies in voluntariness, and it is in the spirit of Christianity that this achieves its full purity.

Sacrifice becomes the cornerstone of the most sacred human acts because of blood. In blood is contained everything that pertains to life: both the sins of the body and the greatness of the immortal soul.25 Among de Maistre’s archaic examples, Egypt holds a prominent place, as, before embalming and mummification, the internal organs of the body were removed and ritually destroyed.26 Yet for all its virtues, the pre-Christian world misunderstood the truth of sacrifice. It grasped its reality, but carried it to excess—even to mass slaughter. De Maistre never denied that paganism contained moral lessons; indeed, he personally admired the greatest thinkers of the Greco-Roman tradition, among whom Plato perhaps stood closest to him. But he was certain of one thing: within the practice of sacrifice, ritual killings carried out by the community were, as we might now put it, evolutionary dead ends.

Up until the crucifixion of Christ, the most acceptable form of sacrifice, arising largely from the biblical Jewish tradition,27 was considered to be the shedding of the blood of animals most closely resembling man.28 Although de Maistre does not mention it, the story of Abraham’s sacrifice provides the origin of the prohibition against the shedding of innocent human blood. The case of Abraham and Isaac also carries the sanctifying assurance that God substitutes the appeasement achieved through animal blood for the sacrifice of human beings.

The absolute, however, is embodied in Jesus Christ, the Lamb of God. His crucifixion is the beginning of the new man, and thus the cornerstone of a new society—the summit that stands above all sacrifice. At the same time, it caps the ceaseless zeal for propitiation that lay behind human sacrifice. This is no mere sacrifice, but Redemption itself. The path of the sinner who seeks forgiveness leads to Christ, and de Maistre, as a Catholic believer, naturally saw in the rites of the Roman Church the pure preservation of that path.

As Joachim Wach points out, every original religious intuition or experience always contains within it a theoretical expression. This intuition often takes symbolic form and encompasses the elements of a central idea or teaching.29 Sacrifice, accordingly, becomes integrated into Europe’s Christian-centred worldview, and de Maistre both stresses and commends the correctness of this. Among mortals, the highest place is occupied by the martyrs who follow Christ, since they voluntarily and innocently shed their blood for a higher good.30 Next, in de Maistre’s understanding, come those who dedicate their lives wholly to God, renouncing most earthly joys in the process. The renunciations that arise from sacred vows also count as sacrifices. Finally comes the ordinary person, who, having taken up his cross, gives up various things for the preservation of his community.

Summary and Conclusions

If we examine all of de Maistre’s writings in which the outlines of a more coherent anthropological perspective appear, it becomes clear that he was engaged in a lifelong search for the great common denominator that binds human societies together. He treated the presence of Providence—and its invisible yet perceptible workings in the processes of history—as self-evident. In this spirit, he sought to identify elements of the isolated cults of pre-Christian or non-European societies. For de Maistre, the connecting link between Christian and pagan, ancient and contemporary, European and non-European forms of society and politics lay in blood sacrifice. Sacrifice, however, can also be understood as an activity of underlying, de facto metapolitical significance. In this sense, sacrifice is in fact adoration—specifically, the Catholic rite of Eucharistic adoration, which sanctifies both the individual and society. It is the mystical operation, the quasi-socialization, of Providence’s all-pervading power. De Maistre himself develops this line of thought in the third chapter of Éclaircissement sur les sacrifices (Clarification on Sacrifices), thereby demonstrating the superiority of Catholic political theology over Protestantism. His metapolitical orientation, however, is expressed still more clearly in other important works, among them the Considérations and Du Pape (On the Pope).

Éclaircissement sur les sacrifices, with its attempt to understand the role of differing cultural values and norms in shaping politics and society, becomes above all a precursor of political anthropology. Yet this ‘understanding’ must not be defined in the modern, fieldwork-oriented sense of the word. The cultural and intellectual milieu of de Maistre’s era was still far removed from the definition of tolerance that would develop in the 20th century, and that still prevails today. The Enlightenment, as a movement, was itself intolerant and elitist, as Robin G Collingwood has pointed out. At the same time, Collingwood also acknowledged that the philosophes’ long-term intentions nonetheless showed the way toward new forms of socio-scientific inquiry and perspectives.31 This claim may be extended even to the theorists of the Counter-Enlightenment. In the case of de Maistre, the note of natural intolerance in his writings likewise contains the germ of a novel—if not fully self-conscious—perspective belonging to the fields of social and political science.

The most comprehensive conclusion of political-anthropological significance that can be drawn from the content of Éclaircissement sur les sacrifices is essentially the recognition that ritual forms of sacrifice retained considerable importance even after de Maistre’s time. The road that led to the establishment of political democracy in the modern sense was paved with sacrifices—and thus, more often than not, with blood—just as in earlier eras, which de Maistre, without claiming to be exhaustive, had sought to illustrate. As an example, we may point to the immeasurable bloodbath of the Second World War, on whose altar new (or drastically altered) states came into being. Not least, the victory of the Western powers served as a catalyst for the full liberalization of Europe, with the attendant welfare state and social peace, and for their long-term preservation.

Another component of de Maistre’s outlook, one that approaches political anthropology, is his early critique of scientism. The break of modern politics with the traditional carried with it ruptures in the world of science as well. The desire to erase traditional problems and presuppositions and to replace them with new ones may be regarded as a general aim of the moderns.32 This was pointed out by Hannah Arendt, Leo Strauss, Eric Voegelin, Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, and many others. At the end of the 18th and the dawn of the 19th century, de Maistre sought to formulate precisely this problem. Nor was this an altogether unique endeavour for the time, since even the most iconic thinkers of the time, including Immanuel Kant, were concerned with questions of scientism and technocracy. De Maistre’s most interesting writing on the subject, his fragmentary ‘Essai sur les Planètes’, nevertheless shows that he feared for the ancient and Christian roots of Europe’s anthropological tradition in the face of these developments.

Taken as a whole, then, each of the works discussed here contains within it the roots of the discipline of political anthropology. De Maistre was not a practitioner of political anthropology, but rather its instructive forerunner. As such, his writings may provide extremely important and useful contributions to its expansion and reinterpretation.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon

NOTES

1 Joseph Eaton, ‘“This Babe-In-Arms”: Joseph de Maistre’s Critique of America’, in Carolina Armanteros, and Richard A Lebrun, eds, Joseph de Maistre and the Legacy of Enlightenment, Voltaire Foundation, 2011, pp. 31–32.

2 Joseph de Maistre, Elmélkedések (Reflections), Századvég, 2020, p. 80.

3 Joseph de Maistre, ‘Essai sur les Planètes’ (‘Essay on the Planets’), Venice, 1799, Archives de Joseph de Maistre et sa famille, 2J20, 653–672, in Richard Lebrun, ed, The Works of Joseph de Maistre, Charlottesville, VA: InteLex, 2008.

4 De Maistre, ‘Essai sur les Planètes’, p. 23.

5 Eaton, ‘“This Babe-In-Arms”: Joseph de Maistre’s Critique of America’, p. 43.

6 De Maistre, Elmélkedések, p. 127.

7 Carolina Armanteros, ‘Maistre’s Rousseaus’, in: Carolina Armanteros, and Richard A Lebrun, eds, Joseph de Maistre and the Legacy of Enlightenment, p. 79.

8 Armanteros, ‘Maistre’s Rousseaus’, p. 102.

9 Richard A Lebrun, Joseph de Maistre: An Intellectual Militant, Kingston, 1988, p. 163.

10 De Maistre, ‘Essai sur les Planètes’, p. 20.

11 De Maistre, ‘Essai sur les Planètes’, p. 22.

12 Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, L’Histoire naturelle, générale et particuliére, avec la description du Cabinet du Roi (Natural History, General and Particular, with a Description of the King’s Cabinet), Vol XIV, ‘Nomenclature des Singes’, ‘De la dégénération des Animaux’ (‘Nomenclature of Monkeys’, ‘On the Degeneration of Animals’), Paris, 1766.

13 Attila Károly Molnár, A jó rendről (On Good Order), Barankovics István Alapítvány, 2010, p. 34.

14 De Maistre wrote his work Éclaircissement sur les sacrifices (Clarification on Sacrifices) in 1809, while he was in St Petersburg as the ambassador of Savoy (Attila Károly Molnár, ‘Hang a forgószélből’[Voice from the Whirlwind], in: Attila Károly Molnár, Idealisták és realisták [Idealists and Realists], Századvég, 2023, p. 124.)

15 Joseph de Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések (St Petersburg Discussions), Századvég, 2021, p. 585.

16 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 580.

17 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 584.

18 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 539.

19 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 540.

20 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 540.

21 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 557.

22 ‘Is it necessary to cite the Tyrians, the Phoenicians, and Canaanites? Must we recall that the Athenians, in their best period, practised these sacrifices every year? That Rome, in urgent danger, sacrificed Gauls?’ De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 559. However, de Maistre also previously specifically discusses the human sacrifice rituals of the Gallic druids. (De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 557.)

23 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 559.

24 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 560. ‘Every time that an Indian woman delivered twins, she had to sacrifice one of them to the goddess Gonza by throwing it into the Ganges; some women are still sacrificed to this goddess from time to time.’ De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 562.

25 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 549.

26 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 546–547.

27 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 551.

28 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 550.

29 Joachim Wach, Sociology of Religion, University of Chicago Press, 1944, p. 19.

30 De Maistre, Szentpétervári beszélgetések, p. 586.

31 Robin G. Collingwood, The Idea of History, Clarendon Press, 1946, p. 81.

32 Gábor Megadja, ‘A demokrácia politikai vallása’ (‘The Political Religion of Democracy’), in: Gábor G Fodor, and András Lánczi, eds, A dolgok természete (The Nature of Things), Századvég, 2009.

Related articles: