Evolutionism—despite the numerous challenges it has faced throughout its history—can still be regarded today as a veritable ‘absolute science’ within the realm of modern natural sciences, particularly biology.

Although philosophical and also biological movements rejecting evolution still exist (such as the Intelligent Design movement, which does not rest exclusively on a simple creationist foundations), the theory still maintains an overwhelming dominance over alternative explanations for the origin of the living world. One such sidelined alternative is the doctrine of the singular creation of immutable species, which was the accepted view of the Catholic Church and Christian denominations in general regarding biological diversity until the mid-20th century. In other words, evolutionary theory has totally triumphed over ‘old-style’ creationism. Pope John Paul II went so far as to declare that evolution is ‘more than a hypothesis.’1

Yet, the question may arise: why should this be a problem for someone who consciously identifies as conservative? Is there perhaps something in Darwinian theory that is incompatible with the doctrine of man’s spiritual origin—a central tenet not only of Christianity but of all religions?

It is difficult to give a simple and reassuring answer to this question. However, we can state that evolution—at least the form of the theory accepted by the scientific mainstream today—poses a very serious, multi-layered problem for those who refuse to accept a materialist worldview. In this context, the Pope’s statement can only be properly interpreted if we consider that the Pontiff cannot accept materialism. For convinced materialists (and atheists), however, the Pope’s statement poses no problem whatsoever; on the contrary, they welcome it as a sign of the Catholic Church’s ‘weakness’ and its ‘retreat’ (or even capitulation) before modern science. For them, accepting evolutionary theory presents no difficulty; indeed, it has become perhaps the most important fundamental thesis of their worldview from the moment Darwin began to preach it.

‘Is there perhaps something in Darwinian theory that is incompatible with the doctrine of man’s spiritual origin…?’

It is evident that Darwinism was treated as an ideological weapon from the very beginning. Darwin himself, early in his life, passing through a ‘deistic’ interlude, reached the borders of agnosticism and atheism.2 Just as the mechanical worldview derived from Newtonian physics sought to banish the ‘irrational’ element from the inanimate world to replace it with calculable material causality, Darwin, as a relatively young biologist, sought to do the same in biology: he was on the road toward pure materialism at the time his theory was being created. Although at this stage he did not openly deny the Creator, he restricted God’s role to merely setting the processes in motion.3 Perhaps he was not led by a priori atheism, but it is thought-provoking that he arrived there so quickly

His followers in the strict sense—whichever shade of the Darwinian thesis they represent—almost without exception explain the origin of life as the material and spontaneous emergence of the living from inanimate matter. Darwin was convinced by his own theory that the universe works ‘without God’. His followers draw even more radical conclusions regarding the ‘origin of consciousness’. They derive man from animals, life from inanimate matter, and matter from mechanical actions ‘occurring’ in a universe devoid of consciousness. The first Darwinists—Thomas Huxley, ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’, Ernst Haeckel, the biologist caught in scientific falsification,4 the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker, and others—exceeding the declared scope of science, almost immediately became enthusiastic advocates of atheism (not to mention the Marxist theory that later utilized evolutionism in the field of political and social ideology).

If this is the case, it might be worth reconsidering whether there is something in the entire theory that—far from being a simple ‘description’ of facts—was constructed from the outset in harmony with a materialist–atheist worldview.

Modern natural science started from the seemingly noble self-limitation of seeking answers to the question of how the world works, leaving the great questions of why to philosophy and theology. As we can see, this was Darwin’s original objective as well. But did the British naturalist remain faithful to this promise? In his tragic trajectory, arching from priestly aspirations to apostasy, do we not see a reflection of the history of the mainstream scientific worldview? Darwin’s theory transformed from a description of ‘how’ into a complete explanation of the world almost within his lifetime—a hidden ‘why’ whose ultimate answer is purposelessness. This is a symbolic fact, the consequences of which are unfathomable, and which we must not ignore today.

Theistic Evolution?

According to the concept of ‘theistic evolution’ formulated by mainstream Catholic theologians, God creates through evolution (and chance). However, this stands in sharp contrast to the warning of Pope Benedict XVI, who stated: ‘We are not some casual and meaningless product of evolution.’5 This papal statement appears to be incompatible with a ‘theistic evolution’ in which chance plays a key role.6

Critics rejecting theistic evolution argue that if God had used the Darwinian mechanism, it would mean that the Creator uses death, suffering, and waste as positive creative tools.7 Critics believe that no coherent thinker with moral sensibilities can accept this ‘cynical’ image of God. If we fail to see the absurdity of this—which is hauntingly reminiscent of the Stalinist principle that ‘when you chop wood, chips fly’—then we are closing our eyes to logic.

The most significant intellectual reason why a non-negligible number of Catholic theologians continue to adhere to this position lies, in reality, in their aversion to the notion of a ‘God of the gaps’—that is, the idea that divine action is confined to those phenomena that nature cannot (or is perceived not to) explain. The Intelligent Design movement, invoking the concept of ‘irreducible complexity’ (for example, in the development of the eye), suggests that God intervenes in nature as a kind of ‘mechanic’. Theologians object that this approach places God at the mercy of scientific progress: should science one day demonstrate that the eye could indeed have arisen gradually, God would simply be pushed out of the explanatory gap.

‘This approach places God at the mercy of scientific progress’

To avoid this difficulty, they incorporate the distinction between ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ causes drawn from scholastic (Thomist) philosophy. On this account, God is the Primary Cause who creates the laws of evolution, while evolution itself functions as the Secondary Cause through which God acts in the world. What this approach fails to recognize, however, is that chance—which constitutes the irreducible core of Darwinism—cannot ontologically serve as a secondary cause, since the very notion of ‘planned chance’ is a logical contradiction.

With this step, they practically dismantle and attempt to overwrite God’s ‘own’ logic with the logic of Darwin and materialism, while failing to notice that they are falling back into the trap of Nominalism (William of Ockham). Since God does not have to adhere to the laws of the system He created (being Almighty, Potestas Absoluta), He can do anything, even declare evil to be good if He wishes. There is no objective good and evil, only God’s arbitrary command. As the Catholic and conservative philosopher Thomas Molnar explained: this thought spawned fatal uncertainty. If God can change the rules of the game at any time, then man cannot trust his reason, nor can he trust the laws of nature.8

Modern Catholic theology, referencing St Thomas Aquinas, often argues that what appears to be chance (contingency) from a human perspective is providence from the divine perspective. However, in the case of Darwinism, this argument commits a serious category error. The argument posits that God does not act as a ‘puppeteer’ in the world but creates beings and grants them the dignity of ‘making themselves’ (the dignity of causality). They use St Thomas’s example: A farmer digs in the ground (cause 1), a robber hid a treasure there (cause 2). If the farmer finds the treasure, it is chance (because the meeting of the two causal chains was not intended by the actors), but from God’s perspective, it is not chance, because He sees and orchestrates the meeting of the chains. The argument suggests that God created the world so that mutations appear statistically random, but in reality, His plan is realized through them.

However, the Thomistic concept of chance merely signifies the intersection of already existing causal chains (the farmer accidentally finds the treasure), not the source of Essence and Information. To claim that God uses the blind chance of mutations—that is, biological noise and decay—to create the human spirit is nothing less than the transfer of creative power to entropy. This is not the ‘dignity of secondary causes’, but the degradation of the Primary Cause and the endowment of Chaos with the possibility of creation. This is theologically worse than not attempting to ‘legitimize’ chance at all, for it demolishes the primacy of Order and Reason—even if that was not the original intention.9

Materialism and Evolutionism

The doctrine of evolution is, in reality, one of the central assertions of modernity, and it is the latent ideological power of this assertion that ‘drives’ Darwinism forward despite scientific facts or logical difficulties. Darwinian evolutionism is closely linked to the ideology of materialism, as it is the only scientific theory that, in principle, would allow for the explanation of the origin of the universe and species without a transcendent source or intervention. As we have seen, it does not necessarily deny the possibility of such a source—hence Pope John Paul II’s ‘acceptance’—but it renders it superfluous for explaining the diversity of living beings (and, in a sense, inanimate things)—at least for those unable or unwilling to look beyond this. And for the vast majority, or at least the greater part of the scientific community, this seems to be a sufficient argument for materialism.

If Darwinian evolution is true, then God—although His existence cannot be disproven by the tools of science—is effectively ‘unnecessary’. Before the advent of modern evolutionism, for natural scientists and natural philosophers—even those who, like Goethe, did not believe in the biblical image of God—it was simply necessary to posit a spiritual First Cause into the system. They had to posit at least one supra-material reality, an ontological guarantee of existence, similar to Aristotle’s ‘Unmoved Mover’, if they wanted to answer the fundamental Heideggerian question: ‘Why is there something rather than nothing?’

For the ‘non-philosophical majority’, too, one of the most important arguments for God was the miracle of the created world: a world whose origin seemed impossible to explain purely from matter—let us add, the abstract concept of ‘matter’ did not exist either— not to mention the origin of conscious spiritual beings like man, whose inner experience of purpose and meaning remains forever irreducible to the blind collisions of atoms. The very existence of the world and the diversity of beings evoked the concept of the necessity of a higher, spiritual power. Once Darwin wrote his book and his followers began to propagate the theory, this solid certainty was, for the first time, called into question for vast masses—without them ever having understood the philosophical premises of Darwinism.

Although, in the sense of rigorous philosophical reasoning, the necessity of a First Cause still stands, philosophy has suffered a profound loss of authority in favour of the empirical natural sciences. As a result, Darwinian evolutionism effectively allows this fundamental question to be set aside in scientific public discourse. Since the methodological naturalism of modern science cannot, by definition, investigate the suprasensible, it must begin with what is sensible. Accordingly, ‘primordial matter’—however it may have come into being—is treated by the theory as sufficient for the emergence of all other beings.

‘Although…the necessity of a First Cause still stands, philosophy has suffered a profound loss of authority’

Although evolutionism does not directly equate to materialism, the two are nevertheless intertwined as closely as possible. Materialism still holds extremely strong positions today (even if not in the classical sense, and is often termed ‘naturalism’, ‘speculative realism’, or other fashionable names). The ‘methodological naturalism’ of the natural sciences validates this materialism appearing in various disguises, even if on the surface it distances itself from metaphysical theories and professes Carnapian positivism.10 Excluding transcendence from the explanation of existence is of paramount importance to many natural scientists. For this reason, evolutionism must be maintained at all costs; indeed, it must be proclaimed as an incontrovertible truth that becomes the very touchstone of common sense.11

This mentality is the product of an attitude independent of the individual’s conscious choice. However, at the highest levels of the scientific elite, this attitude is not merely unconscious drifting, but also a kind of militant defiance, the product of a conscious closure or resistance to the transcendent, which does not stem at all from the ‘compelling’ reality of scientific facts. No one has formulated this intellectual stance more honestly than Richard Lewontin, the world-renowned genetics professor at Harvard University and one of the pioneers of molecular evolutionary biology.

In an article, Lewontin openly admitted that scientists are not forced into atheism by facts, but by their own philosophical commitment:

‘It is not that the methods and institutions of science somehow compel us to accept a material explanation of the phenomenal world, but, on the contrary, that we are forced by our a priori adherence to material causes to create an apparatus of investigation and a set of concepts that produce material explanations, no matter how counter-intuitive…Moreover, that materialism is absolute, for we cannot allow a Divine Foot in the door.’12

This fear of metaphysical conclusions characterizes not only natural scientists but philosophers as well. Thomas Nagel, the famous atheist philosopher at New York University, reveals the modern intellectual’s fear of ‘cosmic authority’ in his work The Last Word:

‘I want atheism to be true…It isn’t just that I don’t believe in God and, naturally, hope that I’m right in my belief. It’s that I hope there is no God! I don’t want there to be a God; I don’t want the universe to be like that.’13

It is therefore evident that the defence of materialism rests not merely on scientific argumentation, but on a deeply rooted existential and worldview decision—a kind of ‘counter-faith’. A peculiar paradox emerges: whereas the dogmatic inculcation of Darwinism in communist systems was at least intelligible as an instrument of state atheism, contemporary liberal education policies—proclaiming themselves ‘ideologically neutral’—often display a similar intolerance.

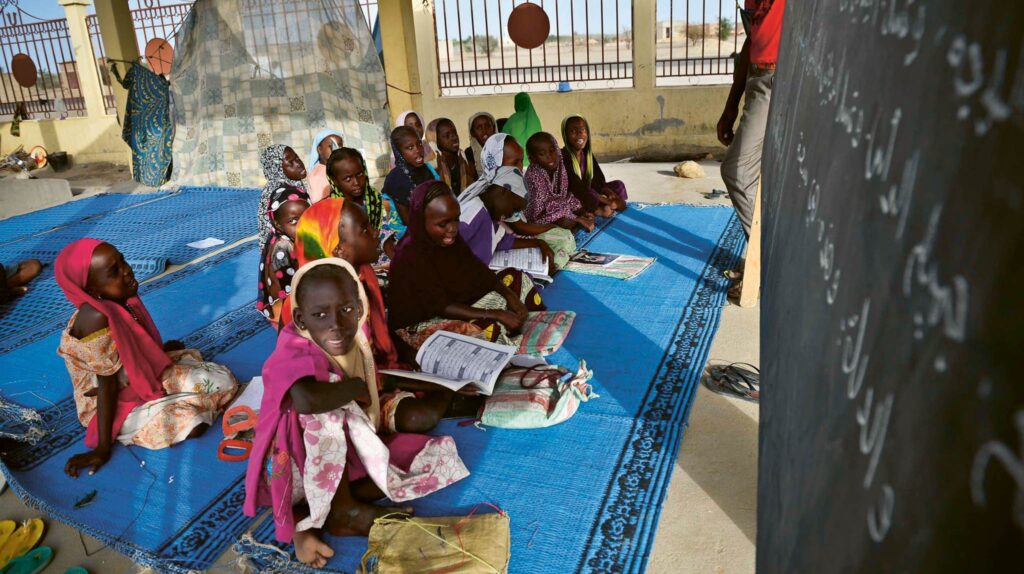

The modern state has quietly relegated religion to the sphere of ‘private opinion’ or subjective values, while elevating materialist science to the status of ‘common, objective reality’, that is, of unquestionable fact. As a result, Darwinism is presented in schools not as a theory among others, but as the only conceivable explanation of reality. The system’s tacit metaphysics thus remains materialism, which—by defining itself as ‘objective science’—is effectively exempted from criticism and from the pluralistic standards routinely imposed on religions. As the American legal scholar Phillip E. Johnson14 has observed:

‘Darwinian evolution…is the creation myth of our culture. It is the officially sponsored, government-financed creation myth that the public is supposed to believe, which creates the evolutionary worldview.’15

In his 1990 article (Evolution as Dogma), he phrases the defence even more sharply:

‘Scientific naturalism is the established religious philosophy of America…[and] the scientific establishment has found it necessary to protect the theory from criticism…’16

The capacity of the atheist–materialist establishment to ‘close ranks’ when the paradigm it upholds with near-confessional commitment is perceived to be under threat is well illustrated by the case of the biochemist Rupert Sheldrake. In his magnum opus, A New Science of Life, Sheldrake proposed the existence of so-called ‘morphic resonance’ and the morphogenetic field, which he describes as non-material in nature. Confronting the problem of ‘form’ at an early stage, Sheldrake argued that DNA—that is, matter—merely manufactures the ‘parts’ (proteins), while the Field provides the ‘plan’, determining their spatial organization and thus giving rise to the final form of a human being, a tree, or even a crystal.

The particles themselves are evidently not intelligent and do not ‘know’ where to arrange themselves. A purely random mechanism of ‘trial and error’ would, in this context as well, lead to absurd consequences: entropy would increase, structures would disintegrate, and nothing would be ‘built’. Common sense, everyday rationality, and higher philosophical logic all suggest that complex forms—such as the eye or a feather—do not arise through blind experimentation, even over the course of billions of years.

‘The particles themselves are evidently not intelligent and do not “know” where to arrange themselves’

According to Sheldrake, the morphogenetic field functions as nature’s memory, guiding cells in their development and organisms in their behaviour by reference to the ‘beaten paths’ established by previous generations. On this account, materialist biology relies on what he calls ‘hand-waving’ when confronted with its most fundamental problems: it possesses terminology for phenomena, but lacks genuine explanations.17

Sheldrake, who also verified his results experimentally, was literally ‘excommunicated’ by materialists: Sir John Maddox, the editor-in-chief of Nature, the world’s most prestigious scientific journal, wrote an editorial titled ‘A Book for Burning’. In the article, Maddox made it clear that Sheldrake’s theory could not be tolerated because, in his view, it attacked the foundations of science. Observe the pseudo-religious language of the statement! ‘His book is the best candidate for burning there has been for many years…Sheldrake’s argument is in no sense a scientific argument but is an exercise in pseudo-science…Many readers will be left with the impression that Sheldrake has succeeded in finding a place for magic within scientific discussion—and this, indeed, may have been a part of the writing of such a book.’18

Maddox, however—despite the illusion created by the authoritarian rhetoric—did not present a single experiment to refute Sheldrake’s claims. Instead of empirical refutation, he marshaled philosophical and methodological arguments, which not only constitutes a category error in empirically based science but also proves that his criticism is the direct consequence of a ‘professed belief system’.

Among his three main arguments attacking Sheldrake was the accusation of ‘vitalism’, claiming that the morphic field is merely a new name for the ‘mystical life force’ (eg, Bergson’s élan vital) and Aristotelian ‘Entelechy’, which science has allegedly ‘surpassed’—though it is unclear how. Invoking ‘more time’ is not an argument for DNA being able to assemble by chance, merely another belief. Most seriously, Maddox deployed Popper’s argument of ‘unfalsifiability’, claiming that the morphogenetic field—being invisible—cannot be experimentally disproven. This, however, was untrue. Sheldrake proposed concrete experiments, which were later tested. The ‘Hidden Images Experiment’ (Collective Learning) became his most famous and elegant demonstration, carried out in cooperation with BBC television.19

Maddox, therefore, did not attack Sheldrake because he did not experiment, but because his results were ‘impossible’ within the materialist framework. This is an open admission that he ‘would not believe it even if he saw it’—a textbook example of fanatical blindness and dogmatism extending to the denial of reality on the part of a ‘leading scientist’. Since he was a ‘member of the guild’, Sheldrake proved far more dangerous to materialism than an idealist philosopher, with whom they would not even engage in debate.

Their procedure, however, is the most obvious refutation of the materialists’ perceived truth. They themselves admit by this that the system has failed. Just to illuminate the power of the establishment: as a result of the scandal, Sheldrake was squeezed out of the academic sphere, his research fellowship was not renewed, and he has since been supported by private foundations.

‘When Maddox (and the elite of the Royal Society) said: “This cannot be true because we say so,” the Royal Society ceased to be a scientific institution’

The harshest irony of fate lies in the motto of the Royal Society: ‘Nullius in verba’ (‘On the word of no one’). This was the cornerstone of modern science against medieval scholasticism. When Maddox (and the elite of the Royal Society) said: ‘This cannot be true because we say so,’ the Royal Society ceased to be a scientific institution. It became a dogmatic church which—unlike the institutional system of medieval Catholicism—defended not a ‘higher truth’ and the meaningful, spiritual order of the universe ‘at all costs’, but an ontological and metaphysical error leading to nihilism.

- This statement was made in Pope John Paul II’s message to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences on 22 October 1996. ↩︎

- This process may be regarded as a form of negative conversion: ‘…disbelief crept over me at a very slow rate, but was at last complete’ (Darwin, Autobiography). He thus arrived at the fulfilment of his disbelief and, with it, a new and profound stage of his fate and inner conscientious struggle: ‘I was very unwilling to give up my belief;—I feel sure of this, for I can well remember often and often inventing day-dreams of old letters between distinguished Romans and manuscripts being discovered at Pompeii or other places, which confirmed in the most striking manner all that was written in the Gospels.’ Quoted in Péter Farkas, ‘Darwin istenhite’ [‘Darwin’s Faith in God’], in Az evolúció mint Isten teremtő logikája, Szent Mór Bencés Perjelség, Győr, 2022, pp. 27–41, at p. 35. ↩︎

- The young Darwin, however, was explicitly religious and prepared for the priesthood. Undoubtedly—as is evident from the numerous letters and quotations cited in the study referenced above—Darwin, although deeply engaged with theology in his youth, remained theologically untrained. He was therefore familiar only with what he described as ‘almost literal’ or ‘weakly allegorical’ interpretations of the Bible. In this process, a decisive role was naturally played by the fact that Christianity—especially in Protestant regions such as England—had, by the mid-nineteenth century, largely lost its metaphysical and symbolic modes of interpretation, becoming a form of simplified ‘moral theology’ increasingly incapable of satisfying intellectual demands. This unfortunate development demonstrates that Christianity had already begun to deprive itself of the philosophical background capable of sustaining the religious faith of the ordinary believer, even before the so-called ‘triumph’ of atheism. ↩︎

- It was Haeckel who produced forged embryo drawings to suggest that the human embryo and that of the dog were identical. Although modern science has long rejected these claims, they persisted in textbooks for decades. Haeckel was also the first to rigidify Darwinism into dogma. He invented phantom creatures—such as Pithecanthropus alalus, the so-called ‘speechless ape-man’—before a single fossil bone had been discovered. ↩︎

- Benedict XVI, ‘Homily for the Mass for the Inauguration of the Pontificate’, St Peter’s Square, 24 April 2005. ↩︎

- Cardinal Christoph Schönborn notes that, according to Church teaching, evolution understood as common descent is possible, but evolution conceived as an ‘unguided, unplanned process’—in the sense advocated by neo-Darwinian ideology—is not compatible with the faith. He argues that proponents of theistic evolution often make the error of limiting the Creator’s role to merely initiating the process, leaving room for the rule of blind chance, which contradicts the divine reason (Logos) manifest in the world. See: Christoph Schönborn, ‘Finding Design in Nature’, The New York Times, 7 July 2005. ↩︎

- According to Wolfgang Smith (Catholic physicist and philosopher), this approach is a metaphysical impossibility. He demands an account for the lack of ‘vertical causation’ in theistic evolution: in his view, God does not ‘tinker’ on the horizontal plane of random mutations and the struggle for existence; rather, living forms (substances) unfold from a timeless, spiritual dimension into physical space. Smith argues that the theological adaptation of Darwinism necessarily leads to a distorted image of God, in which waste and destruction are the engines of creation. See: Wolfgang Smith, The Wisdom of Ancient Cosmology: Contemporary Science in Light of Tradition, Oakton, Foundation for Traditional Studies, 2003, pp. 209–226. ↩︎

- Medieval thought—especially that of St Thomas Aquinas—was unmistakably realist. It recognized that the things of the world, whether concrete beings (such as human beings or trees) or abstract and ‘ideal’ realities (such as goodness or truth), possess a stable essence created by God, which human reason is capable of apprehending. This realist position was denied by Ockham and the nominalists of the via moderna. If universal concepts are nothing more than words—mere ‘empty names’—then, as Tamás Molnár argues, philosophy itself is effectively sentenced to death.

As Molnár demonstrates in his essay ‘Modernitás’ [‘Modernity’], the nominalist turn exerted a decisive influence on the emergence of modern natural science, particularly through figures such as Oresme and Buridan. If the essence of things cannot be known—either because no such essence exists or because God has concealed it—then inquiry is reduced to the examination of motion and relations alone. As Molnár warns: ‘If there are no essences, only relationships, then in dealing with people the temptation arises to develop methods of manipulation.’ (Tamás Molnár, ‘Az átmenet kora’ [The Age of Transition’], Havi Magyar Fórum, September 2002, pp. 58–59, at p. 58.) Most dangerously, this intellectual shift paved the way for scientism, which later emerged in the form of positivist natural science. In doing so, it radically marginalized the intellect (nous)—the faculty capable of grasping spiritual essence and meaning that transcend the mere materiality of things. ↩︎ - The philosophical criticism of this argument, the so-called ‘Thomist evolution’, is detailed by Logan Paul Gage, who points out: St Thomas Aquinas’s concept of chance (casus) refers to the meeting of two independent causal chains, not the creation of complex biological information. The ‘treasure in the field’ example refers to a chance event, not the origin of substances. According to Gage, applying this analogy to the chance of mutations is a serious equivocation. See: Logan Paul Gage, ‘Darwin, Design & Thomas Aquinas’, Touchstone, October 2012. ↩︎

- Carnap’s logical positivism, in principle, rejects materialism insofar as it operates with the concept of substance, dismissing it as a ‘metaphysical theory’. ¹ (Cf Rudolf Carnap, ‘The Elimination of Metaphysics through Logical Analysis of Language’.) Many leading biologists and physicists today, however, do not adhere to this position. Instead, they routinely invoke notions such as a ‘primordial soup’ or even a ‘primordial pizza’—from which life is alleged to have emerged—and speak of a ‘Big Bang’ as the origin of the universe, conceived as a singularity understood entirely in physical terms. ↩︎

- Despite this, numerous scientific and philosophical criticisms exist which Darwinists ignore or do not answer satisfactorily. These range from the observations of the German biologist Jakob von Uexküll in the late 19th century to authors such as Wolfgang Kuhn, the British ornithologist Douglas Dewar (The Transformist Illusion, 1957), or representatives of the American ‘Intelligent Design’ movement (eg, Michael Behe: Darwin’s Black Box, 1996). Also worthy of mention is the ‘organicist’ Roberto Fondi, whose works are unfortunately available almost exclusively in Italian. Although these criticisms operate on different philosophical and scientific levels, the mere fact that they deny Darwinism does not make them ‘unscientific’. A regrettable characteristic of public scientific discourse is that these works—apart from a few sporadic exceptions—are not submitted for debate but are silenced. ↩︎

- Richard Lewontin, ‘Billions and Billions of Demons’, The New York Review of Books, 44/1, 9 January 1997, 31. Richard Lewontin (1929–2021) was one of the most influential evolutionary biologists and geneticists of the 20th century. At the same time, Lewontin never hid his worldview. He proudly professed to be a Marxist. His most famous book (with Richard Levins) is The Dialectical Biologist. In it, he openly applies the principles of dialectical materialism to biology. He vehemently attacked sociobiology and evolutionary psychology (eg, his colleague E O Wilson) because he considered it ‘bourgeois science’ that seeks to justify social inequalities with genetics. ↩︎

- Thomas Nagel, The Last Word, New York, Oxford University Press, 1997, pp. 130–131. ↩︎

- Phillip E Johnson (1940–2019) was a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley. The publication of his 1991 book Darwin on Trial marks the birth of the Intelligent Design Movement. According to Johnson, every civilization needs a story to explain: ‘Who are we? Where do we come from? Why are we here?’ In Christian civilization, this was provided by the Book of Genesis. The modern, secular state (which has discarded God) needed a new, atheist creation myth to justify its existence. ↩︎

- Phillip E Johnson, Darwin on Trial, Downers Grove, InterVarsity Press, 1991, pp. 133–134. ↩︎

- Phillip E Johnson, ‘Evolution as Dogma: The Establishment of Naturalism’, First Things, October 1990, pp. 15–22. ↩︎

- ‘Morphic fields are fields which play a causal role in the development and maintenance of the form of systems at all levels of complexity…They are fields of structure…These fields are not made of matter or energy but are invisible and intangible spatial structures which impose patterns on physical and chemical processes.’ Rupert Sheldrake, A New Science of Life: The Hypothesis of Morphic Resonance, London, Icon Books, 3rd ed, [1981]2009, pp. 110–111. ↩︎

- John Maddox, ‘A Book for Burning?’, Nature 293, 24 September 1981, 457–458. When such a furious campaign (book burning) is launched against a theory, it always indicates: it is very much testable, and the result is dangerous to the dogma in power. ↩︎

- According to the test, a blurry, indistinguishable black-and-white image (eg, a bearded man’s hidden face or a Dalmatian in patches) was shown to people on one side of the world (eg, in Australia). They measured what percentage recognized the hidden figure (approx. 1–2 per cent). Then, the BBC showed the solution (where the face is) to millions of people in England during prime time. After the broadcast, the recognition rate was measured again among people (eg, in Africa or America) who had not seen the English programme. The recognition rate jumped significantly (up to 7–10 per cent). Since millions of minds ‘learned’ the pattern in England, the pattern entered the morphic field, making it easier for other people (who were attuned to the image) to ‘download’ the information. ↩︎