‘The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt.’[1] This strikes me as one of the fundamental problems of the human psyche: the smarter you become, the more you realize how much you don’t know, ideally fostering a sense of humility. This is reflected in the so-called Dunning-Kruger effect: people with greater skill tend to underestimate their abilities, while those with less skill tend to overestimate them.

I emphasize the word ideally here, as research[2] as well as common experience suggest that more intelligent people are often not humbler (or moral) to begin with. Intelligence often also comes with a (false) sense of pride and arrogance about your own intelligence. I believe this is primarily because people attribute their innate talents to themselves, rather than to God (or the universe).

Even though all societies are tempted by arrogance and pride (not for nothing one of the worst cardinal sins), Western society has a natural magnetism to it. This is somewhat understandable, as the West has contributed disproportionately to many of the world’s modern developments, especially through its pursuit of morality (for example, dignifying every human being as created in the image of God, the abolition of slavery, and so on) as well as scientific and technological advancement.

That is not to say that other great civilizations have not contributed significantly, or that the West has not committed many atrocities (for example, the Holocaust). Yet just as an intelligent person who should know better often fails to live up to that calling, so too does the West struggle with its own pride.

It is not for nothing that the Western story is often (most famously by Oswald Spengler) associated with the classical Germanic legend of Heinrich Faust, which was popularized by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Spengler in Der Untergang Des Abendllandes even goes as far as to call the Western culture in essence Faustian. Spengler thereby compares the Western way of life with that fictional story of Faust. Western society has, like Faust, great strength that also turns into its biggest weakness, and for Spengler this is what will lead to the inevitable downfall of the West. Pride comes before the fall.

‘Western society has, like Faust, great strength that also turns into its biggest weakness’

To summarise the story of Faust: he is one of God’s favourite creations, and so pride is not difficult to imagine on Faust’s part. Mephistopheles (Satan), seeking to prove to God that even His most gifted creation can fall—and that humanity is therefore doomed—makes a wager that he can lure Faust away from his god-given path, his actualization of potential, his telos, and lead him into darkness.

Faust is an intelligent and inquisitive man who longs to understand as much of the world as humanly possible. For him, this pursuit of knowledge offers the delight of grasping more of God’s creation and thereby drawing nearer to God Himself. Yet this noble aspiration becomes his undoing. Filled with pride, Faust is seduced by Mephistopheles’ promise of unlimited knowledge (and therefore power). Eating from the symbolic tree of knowledge proves irresistible. In the end, he trades his soul for this power and loses his way, descending into sorrow and damnation—a fall echoing that of Adam and Eve in the original sin.

The story of Faust is strikingly powerful for the modern person, for it speaks not only to our present societal condition but also to our inner demons. There is a sense of recognition in it: our contemporary world has become one-dimensionally obsessed with a reductionist rationality—an impulse toward ‘unlimited knowledge’—that expands for its own sake. We build faster internet to enable larger files, which in turn demand even faster internet, and so the cycle continues.

In earlier essays, I focused mainly on what has been lost (the vita contemplativa, family and community life, the transcendent) and on the forces that have replaced these goods (consumerism, nihilism, and so on). Yet one crucial part of this equation has been missing: the role of the infocracy.

As human beings throughout all of history have struggled to find proper ways to live together in a way that enables flourishing individuals, communities and societies, and therefore spend a great deal, with trial and error, to explore different ways of cooperation, our modern times provide their own set of challenges. Some of these are universally human, as with the danger of arrogance and pride, and others have to do with our modern form of technocracy, disenchantment and meaninglessness.

Although consumerism and nihilism serve as modern coping mechanisms for our ‘disenchanted society’, their primary effect has been to leave behind a profound void—one in which new ideologies and modes of social organisation can take root. Much of this void has been overtaken by one-dimensional rationality, or what I call ‘zombie-rationality’, as it is not truly rational to reduce the complexity of life to one dimension. It becomes life’s mindless purpose—meaning that it is not a conscious purpose, but an aimless push towards an endless abyss of more one-dimensionality—which I have described before in relation to Friedrich Junger’s work on technology.

Yet, the final piece of the puzzle is that some of the aimless one-dimensionality has actually been channelled into a new ideology. This ideology, called dataism, is in a dialectical struggle with the ‘general technocratic impulse’ that has no desire to abolish itself.

The Destructive Nature of Dataism

Dataism, in essence, is the ideological and modern belief that data or information is the most important resource for understanding and organizing reality, including human societies. In short, dataism holds that the universe and everything in it can ultimately be understood as flows of information—if only we could find a way to process all the data efficiently enough. ‘Dataism absolutizes information. It equates truth with information. Information is taken to be an absolute value, which renders interpretation and reflection superfluous.’[3]

General technocracy, in contrast, holds no fundamental belief and does not want to be held back by any thoughts of ultimate reality. It only ‘mindlessly’ seeks to continue its task as efficiently as possible, no matter what it is, whether there is a need for it, or even if it might cause harm to the individual performing the act or to others. ‘Technique knows no aim beyond its own further perfection. It progresses without regard for ultimate goals. Its movement is one of aimlessness, for it advances solely for the sake of advancing.’[4]

Both technocracy and infocracy (dataism) share, however, that they psychologically derive their power from a source different from previous ‘regimes’. In early modernity, power and order in society were established through top-down prohibition, repression, and surveillance of many aspects of people’s lives. The virtues that the state instilled in its citizens were discipline, obedience, and adherence to rules. This way of organizing society has its roots in Protestant ethics, in which the primary societal dignity of the individual is found in hard work and discipline. This is what Byung-Chul Han calls ‘biopolitics’. The discipline primarily focuses on regulating the body and creating obedient ‘factory workers’ who, in a physical sense, obey the ‘rule-based order’.

This is not what the infocracy that has risen in late modernity uses. The infocracy, by contrast, gains control by promoting indulgence and seduction, thereby making people voluntarily part of the information flow. Instead of saying no to us, the dominant forces in society flood us with choices, stimuli, and data. In this way, we become actors in our own self-exploitation and actively choose to give up our own freedom. This is what Han calls ‘psychopolitics’. ‘Unlike the disciplinary regime, which worked through prohibition, the regime of information operates through indulgence. Instead of denying, it permits. Instead of suppressing, it inundates. This is precisely how it exerts its power.’[5]

‘We become actors in our own self-exploitation and actively choose to give up our own freedom’

A good example of this is witnessed in how social media operates. Social media is based on algorithms that aim to keep us ‘engaged’ on the platform for as long as possible. It uses increasingly novel stimuli to create dopamine hits that are highly addictive. A recent study indicates that 54 per cent of adolescents in the US admit that it would be difficult to give up social media, while 36 per cent admit that they spend too much time on social media, yet continue to do so. Here, dataism once again kicks in. The responses to the increasing information flow make it possible for algorithms and AI to create behavioural profiles that increasingly optimize engagement, making the platform more addictive on an individual level.

Unlike biopolitics, which at least created a shared reality in which people were disciplined in similar ways and therefore had a shared sense of identity, the infocracy fragments and atomizes the individual to optimize the information flow per person. Moreover, dataism is not concerned with truth. As it does not have to deal with physical reality, it is not directly constrained by physical truth. Therefore, the infocracy has been able to create a post-truth society in which the information flow is oriented primarily toward circulation, speed, and visibility rather than truth. This increasingly undermines a shared basic notion of reality, now commonly described as ‘fake news’. ‘Infocracy does not abolish truth; rather, it corrodes it. In the regime of information, truth gives way to transparency, to speed, to circulation. This is how infocracy creates a post-truth society.’[6]

As truth is no longer a core aim of infocratic society, communicative action, one of its principal champions as powerfully described by Jürgen Habermas, has also been forsaken. Habermas’s ideal is that communication aims at mutual understanding, deliberation, and truth-seeking through rational discourse. One could say that this has been a fundamental principle behind the success of Western culture, from the antiquity of Plato and Aristotle all the way through the Enlightenment and into early Modernity.

In its place, we have what Han describes as ‘digital rationality’. This is a mode of communication in which deliberative depth and truth-orientation are stripped away. As a result, it produces digital communication that is fast, fragmented, and optimized for clicks and circulation. Whereas communicative action creates a community of ideas and people engaged with them, digital rationality produces communication without community.

In a way, this completes the post-modern artist’s ideal. Post-modern artists, who also do not believe in concepts such as reality or truth, aim to create nonsense and play whose sole purpose is to demonstrate the demolition of art, which once embodied metatruth itself. A famous example is Comedian, a 2019 ‘artwork’ by the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan. The entire ‘piece of art’ consists of a fresh banana duct-taped to a wall. The artwork was created three times: the first two bananas were sold for $120,000 each, and the second was later resold for $6.2 million to cryptocurrency entrepreneur Justin Sun. The third was donated to the Guggenheim Museum.

Although impressive in some ways that Cattelan was able to pull off this daring insult to art as an institution, the dataist doesn’t have to work so hard. The infocratic playground—the digital world—has already exploded the limits of rational, ordered discourse and increasingly deconstructed it. Thus, even the post-modern impulse is neutralized in the infocratic society. The digital world has already done what Cattelan and his like-minded ‘artists’ could never have dreamed of doing: creating a fully fragmented, post-truth communication landscape.

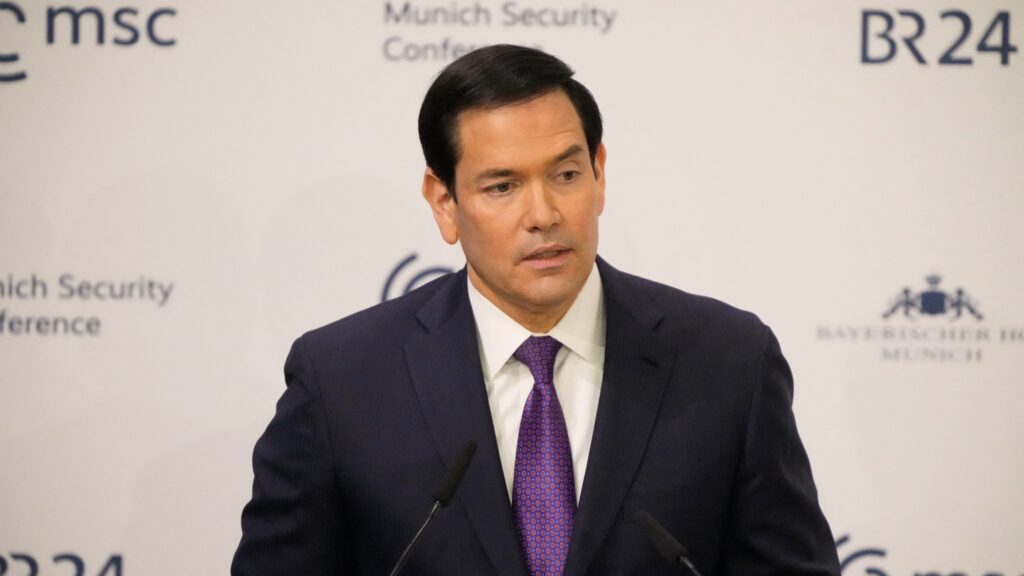

Another verbal example of this—one of many that can be encountered online daily—is a recent conversation between public intellectual, podcast maker, and author Konstantin Kisin, and Ann Coulter, a prominent American conservative political commentator, columnist, and author. The entire conversation exemplifies how the infocracy produces influencers who are not selected based on truth-seeking or expertise, but on how much information flow they can generate by ‘engaging’ a large audience, often through unnuanced one-liners.

Yet, there is one crucial moment that exemplifies is this more than any other. In the interview, Kisin and Coulter at some point discuss the war in Ukraine. The key point for me is the following part of the conversation:

Coulter: ‘He definitely wants all of Ukraine. It is historically part of Russia.’

Kisin: ‘Not all of Ukraine is historically part of Russia, but fine. I am from Russia, so...So Western Ukraine used to be part of Poland. Eastern and most of Southern Ukraine was part of Russia.’

Coulter: ‘Okay, I am not believing you.’

Kissin: ‘You are not believing me? No, why not?’

Coulter: ‘I want to look it up.’

For argument’s sake, let us not dwell on one’s appraisal of Coulter’s stance on the Ukraine war, as it is irrelevant to this essay. What matters is the fact that a prominent public figure like Coulter, who frequently comments on the war in Ukraine, is unaware of some of the most basic facts about the country and is unwilling to acknowledge them. This demonstrates, beyond cognitive dissonance, something crucial: Coulter’s ability to build a credible reputation as a public intellectual while discussing such a sensitive and significant topic—despite lacking fundamental knowledge—is not solely her fault.

In a sense, she has become a victim of the infocracy herself. As noted at the beginning of this essay, less intelligent individuals often display greater certainty in their convictions. Infocratic algorithms exploit this tendency, elevating less-intelligent but sufficiently engaging individuals to become influential nodes in the information stream.

‘In the end, the Dadaists’ play with nonsense, their destruction of sense, has been realized by digital communication itself. Digital rationality no longer serves communicative understanding; it produces information without meaning, communication without community.’[7]

The Interpersonal Health Paradox

As the infocracy itself has fundamentally changed the cultural psyche of people, they have had to reinvent the dynamics of their social relationships to fit the new cultural reality. During early modernity, collective and communal social relationships have fragmented as people became more socially independent and individualistically focused. The progressive social emancipation further made it possible for relationships to primarily form on the individual level.

Yet, as late modernity has increasingly fallen under the spell of the infocracy, the social fabric of these individual relationships has eroded in turn. As a result, so-called ‘experimental individualism’ has emerged as the new dominant form of social relationships. This new kind of social dynamic has emerged as a response to the influence of a newly dominant few, who see intimate relationships as a threat to the self-fulfilment that the infocratic society promotes: self-indulgence.

‘As late modernity has increasingly fallen under the spell of the infocracy, the social fabric of...individual relationships has eroded in turn’

In this new social reality, to be committed means to lose opportunities that constantly arise in the fragmented society, as well as to create a burden of commitment that becomes unbearable to the ‘free and hedonistic individual’. Thus, the experienced advantages of committed relationships are outweighed by their cons. When people do still engage in human relations, this is increasingly marked by this ‘conformist consumption’ lifestyle, in which the totality of life revolves around overworking together to overconsume ‘together’.[8].

In line with the rise of the ‘digital consumer society’, people increasingly view interpersonal relations through a hedonistic, consumerist lens. Practically, this means that other people must compete with algorithms optimized for one’s pleasure. It is therefore unsurprising that, with the rise of ‘AI dating chatbots’, adoption is rapidly increasing. The ultimate relationship according to these infocratic norms is the most self-indulging relationship imaginable. Whereas this ideal used to be sought in other human beings, increasingly narcissistic relationships—often ending in break-ups or divorce—have begun to fall short.

AI technology, by contrast, can fulfill this egocentric ideal to an extent that no human ever could. As people seek entities that provide the illusion of reciprocity without the commitment, vulnerability, or intimacy of a real relationship, they find a new ‘freedom’ in abandoning the challenges of human connection. For some, this trend seems inevitable, and they fully embrace AI dating bots. It should therefore not come as a shock that one in four people worldwide report having formed a romantic or emotional bond with an AI bot—and among Gen Z, this number rises to nearly 40 per cent.

Intimate and local social connections have simultaneously become part of a competitive ‘market’, in which interpersonal, local relationships must compete for time and resources with online activity as well as interactions ‘with’ people across the globe. These global digital relationships lack the embodied intimacy of traditional connections. To compensate for this qualitative deficit, a voyeuristic style has emerged, in which the whole world becomes one’s ‘family’, dominating the social landscape on a neurotic scale.

‘These global digital relationships lack the embodied intimacy of traditional connections’

This pattern aligns closely with the infocratic stimulation of a continuous information flow. The ultimate exemplar—and the person with status—in this infocratic society is the influencer, who embodies all of these principles. The influencer is not social in the traditional sense of forming meaningful connections with others, but magnetic to a global, anonymous audience, drawing attention through an indulging flow of communication-entertainment.[9]

This new social order has also come at a serious cost to our mental health. Although much could be said about our eroding mental well-being, as I have described in part in my previous essays, the most obvious example of infocratic social dynamics can be found in the prevalence of social phobia. While causality is difficult to empirically determine, it is logical to assume that the alienation of local relationships has at least in part contributed to the so-called ‘epidemic of social phobia’. Over the last 20 years, social anxiety disorder (social phobia) has increased worldwide, particularly in the West. In the US, the prevalence has doubled from 5 per cent[10] to 10 per cent[11] of adults. In Europe, the 12-month prevalence has risen from 2–3 per cent[12] in the early 2000s to 4–6 per cent today.

Another striking consequence of the erosion of local, individual relationships has been the rise of petism. Petism is a predominantly Western phenomenon in which an increasing number of people—primed by the infocracy to seek low-commitment relationships—attempt to scratch the intimacy itch from a distance with pets.[13] In the end, no matter how dominant the social norms of the infocracy may be, we remain social creatures at our core, even if we collectively forget it.

Where Do We Go from Here?

As we begin to see the severe downsides of the infocratic age, more and more people are seeking a path forward, away from our dataistic present. For now, much of societal attention is focused on the symptoms of the infocracy (eg, the impact of social media on mental health and the social fabric). This is already a good first step toward creating greater societal awareness of the drawbacks of our time.

Yet, without intellectual and political leaders who are able and daring enough to go beyond the surface-level symptoms of the infocracy, our capacity to reform society and adapt to a post-infocratic world becomes increasingly limited. It would be like fighting the weather: we might cool our houses with air conditioning, but we cannot stop the heat from entering in the first place. I therefore hope that we can once again draw on human ingenuity and our quest for redemption to find a path forward.

[1] Bertrand Russell, ‘The triumph of stupidity’, In H Wood (ed), Mortals and others: Bertrand Russell’s American essays, 1931–1935, Vol 1, Routledge, 1933, pp. 28–32.

[2]Elizabeth R Tenney, Jennifer M Logg, & Don A Moore, ‘(Too) smart for their own good: The disadvantages of intellectual humility and advantages of intellectual arrogance’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 116(3), pp. 532–560, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000146.

[3] Byung-Chul Han, Infocracy: Digitization and the Crisis of Democracy, D Steuer (trans), Polity Press, 2022.

[4] Friedrich Georg Jünger, The Failure of Technology: Perfection Without Purpose, F D Wieck (trans), Ohio University Press, original publication: 1946, 2015.

[5] Han, Infocracy: Digitization and the Crisis of Democracy.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] J L Ozanne, & J B Murray, ‘Uniting critical theory and public pol- icy to create the reflexively defiant consumer’, In R P Hill (ed), Marketing and con- sumer research in the public interest, London, Sage, 1996, pp. 3–15.

[9] Philip Cushman, Constructing the self, constructing America, Reading, MA, Addison-Wesley, 1995.

[10] R C Kessler, P Berglund, O Demler, P Jin, K R Merikangas, & E E Walters, ‘Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication’, Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 2005, pp. 593–602, https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593.

[11] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Anxiety and depression: Data from the National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2019–2022, National Center for Health Statistics, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db465.htm.

[12] K Beesdo-Baum et al, ‘The prevalence of social anxiety disorder in adolescents and young adults’, Psychological Medicine, 42(1), 2012, pp. 11–20, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711000835.

[13] R C Simons, ‘Sorting the culture-bound syndromes’, In R C Simons & C C Hughes (eds), The Culture-Bound Syndromes, Dordrecht, Reidel, 1985.

Related articles: