The term political theology was first introduced by Carl Schmitt in his book Politische Theologie in 1922, but has since been used in many different senses.1 According to one influential interpretation, the concept refers to the political role of religion. By definition, this can only be applied to societies and historical eras in which religion has or had a fundamental political role. The classic expression of this view can be found in the work of Ernst Kantorowicz.2 Kantorowicz and other authors who fall within this approach have employed the concept of political theology to help them interpret ancient societies and the world of the Middle Ages. However, Schmitt used the term in a quite different sense. He applied it specifically to modern, secular society. Max Weber started from the notion of charismatic leadership, according to which a relationship of ruler and ruled can develop when members of a political community come to believe in the special ability of a leader, and therefore accept the decision-making status of that individual. Of course, it is not the qualities the leader actually has that matter, but what the masses believe them to be. So it is a matter of faith, and of political myth based on it.3 Schmitt’s views are quite close to Weber’s on this point.

Schmitt’s oft-quoted dictum states that ‘[a]ll significant concepts of the modern theory of the state are secularized theological concepts’.4 This is in fact the key phrase in Schmitt’s political theology. Theological concepts are important for the political interpretation of our present moment in two ways. Firstly, because of their historical origin—that is, they originated in the worldview of pre-modern eras—religious concepts have played a fundamental role in shaping the modern world, while secondly (and Schmitt was convinced of this) the conceptual frameworks of modern states and legal systems overlap with theological concepts. In both cases, therefore, though we live in a secular age, it is essential to examine theological concepts.

One of the primary questions of scientific and political interest to Schmitt was what the modern, secular state does with godlessness.5 Does it bid a permanent goodbye to God, or has it rather created ‘gods’ of its own, to replace the lost, expelled God? And what political role can Catholicism play in this non-religious world? Schmitt was thus not chiefly interested in the study of Catholicism from a religious, but rather from a purely political point of view, and he understood that we can find structural analogies between religious and modern, secular worlds. He represented this view forcefully in his aforementioned 1922 work Politische Theologie. In a study entitled Römischer Katholizismus und politische Form, written a year later, he dealt with the possible political role of Catholicism and the closely connected nature of representation.6 Here, however, we will concentrate on the issue of political theology.

Although secularization did not redefine religious concepts in a religious sense, political-legal concepts have nonetheless taken on similar forms to those found in the religious world.7 That is why Schmitt sees the search for analogies as a fruitful method. He found the historical roots of this approach in Leibniz, who emphasized the similarities between the methodologies of jurisprudence and theology. But in Hans Kelsen’s work he also found an example of the same approach in contemporary state and legal theory. One analogy, for example, is that a state of exception has a similar meaning in jurisprudence as does a miracle in theology. There are also strong parallels between the omnipotent God and, in the realm of politics, the omnipotent sovereign.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the disappearance of the decisionist and personal elements of sovereignty was counterbalanced by the increasing prominence of democracy and the rule of law

When it came to analogies, Schmitt emphasized the conceptual sociological approach. This approach examines how the meanings of political and legal concepts are related to the historical-political reality of the era in which they emerged. Thus, for example, he finds that in seventeenth-century Europe, monarchy corresponded to the conception of sovereignty at the time. By this time, legal thinking had become independent, and lawyers had defined themselves independently of theology, migrating from the sacred to the profane world. However, during this migration, they secretly or openly took certain sacraments with them. The state adorned itself with forms of ecclesiastical origin. Its power had been secularized but not yet profaned. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, however, the disappearance of the decisionist and personal elements of sovereignty was counterbalanced by the increasing prominence of democracy and the rule of law. The roots of this shift lay in the rationalism of the Enlightenment. That is because the scientific worldview was also spreading to the realm of political ideas, which meant that the rule of law, which did not recognize the exception, began to assume a preeminent position. As rule became impersonal, the act of decision-making also disappeared, as a decision can only be made by a person, and thus cannot be interpreted in an impersonal context. As a result, intellectual currents developed in such a way that the decision-making sovereign no longer had a place. Democracy is about the masses, and the political expression of the masses. However, the rule of law and its practical enforcement place limits on the political community when it seeks to implement that will. The sovereign is no longer a person, but a great machine. A self-operating machine.

Despite all these changes, it is becoming clear that we may encounter similar phenomena in different historical eras, if not in content then in form. Certain concepts show similarities in their formulation and function, as described earlier. I would add to this another one of Schmitt’s key concepts: the significance of the exception. Why is it important to approach the subject in question from the point of view of the exception? According to Schmitt: ‘In the exception the power of real life breaks through the crust of a mechanism that has become torpid by repetition.’8 That is, the social phenomenon, the mode of operation of a social institution, is now accurately seen in the exception, because only when looking at the exception do we see the real authority of a person, a group, or an institution. In short, we see its nature.

Among contemporary thinkers, Schmitt’s concept of political theology is most closely associated with the Italian legal philosopher Giorgio Agamben. Agamben’s work partly supplements and partly corrects Schmitt’s propositions, but in its overall thrust it can be seen as a continuation. Agamben studied law and philosophy, wrote his doctoral dissertation on the influence of Simone Weil’s political ideas, and attended Martin Heidegger’s influential seminars in Le Thor, France, from 1966 to 1968, as part of his postdoctoral studies. The rediscovery and reconceptualization of the homo sacer (holy man) brought him international fame and recognition, and he devoted several volumes to elaborating these ideas.9 His work was most influenced by Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, Michel Foucault, Martin Heidegger, and Carl Schmitt.

Agamben considers it a crucial feature of modernity that human life as such (or bare human life) has become an essential object in the plans and calculations of state power. The state of exception means the suspension of law. According to Agamben, not only are Schmitt’s writings about the state of exception still relevant today, but the concept has only now been fully realized: ‘In truth, the state of exception is neither external nor internal to the juridical order, and the problem of defining it concerns precisely a threshold, or a zone of indifference, where inside and outside do not exclude each other but rather blur with each other.’10 A state of exception is a situation in which applicable laws are not enforced while, on the other hand, actions are freely conducted which are not condoned by law. Power and authority diverge. That such deviations from the normal legal system are possible is shown by the many instances in which they have occurred over the past two centuries. Such discrepancies may go under many names: a state of siege, a state of emergency, or wartime conditions, to name just three. But in all these cases, the law itself had defined the exceptional rules which are to be applied. That is, determining the degree of deviation from the normal situation remained within the ambit of the law. The state of emergency, on the other hand, depends on power outside the law.

It is difficult to define a state of exception precisely because, like civil wars, uprisings, and resistance movements, it lies on the ambiguous and uncertain frontier between law and politics. The situation is paradoxical: a state of emergency is a legal condition which cannot take legal form. The law governs life and regulates living conditions. It is precisely for this reason, in the theory of the state of emergency, that the moment may be seized, altering the relationship between people and the law, and showing how it may be lost. The state of exception is the no-man’s land between public law and political facts, between legal systems and life, and is thus a borderline situation.

The novelty and intellectual power of Agamben’s analysis also lies in the manner in which he presents it: the state of exception is not, in fact, an exceptional phenomenon. Indeed, it has become the norm in the modern age. When the state of exception becomes the rule, one experiences the absolute indistinguishability of fact and law, life and legality, nature and politics. We may observe how many times since the French Revolution governments have suspended normal legal procedures, that is, the entire legal system then in force. The example of Nazism shows that such a suspension can remain in place for a long time. But it is not only totalitarian regimes that have seen the introduction of states of emergency. According to Agamben, the United States Patriot Act of 26 October 2001 and related provisions, which allowed, inter alia, the detention of suspects for years without judicial review, created a state of emergency in the United States.

The notion of a state of emergency does not necessarily have to be associated with the image of a dictatorship based on violence. Rather, we ought to see it as a phenomenon, such as when life and law do not fit together, or when the decision-making scope of law and politics differs. The existence of this difference is not in itself good or bad, but stems from limitations on the degree to which social life can be formalized. Law, as lawyers are well aware, has no substantive link with either justice or truth. Therefore, the law should not be confused with morality or theology. An essential feature of law is judgment. Is the judgment based on a true, veridical assessment of the situation, and is the decision itself fair? Well, all of these can be and are among the ideals to which judges aspire, but the judgment itself as a legal quality does not stem from these.

Civil disobedience is not explicitly defined in law. If it were, we would not be speaking about disobedience at all, but about the exercise of rights

Dictatorships show that the state of emergency can extend to the physical elimination of human life, but its scope is narrower in democratic settings in that it threatens not life as such, but a specific aspect concerning the tolerability of our lives. In the latter case, we can also reverse the basic situation, as when the state of emergency is not defined by a state or political decision, but by the decision of a citizen. Just think of civil disobedience, when a citizen unilaterally decides to suspend the rule of law as imposed in a particular domain. After all, civil disobedience is not explicitly defined in law. If it were, we would not be speaking about disobedience at all, but about the exercise of rights. Judgment may be based not on the legal code, but on the basis of legal and political traditions. The state of exception irritates and at the same time inspires the lawyer. In a state of exception, as in times of scarcity or a no-man’s land, one sees both the importance of a legal structure and the limits of the law.

The third author to be briefly considered is Johann Baptist Metz. Metz attempted to reconceptualize the problems of political theology, but as a theologian, not as a philosopher or a historian of ideas. It is necessary to speak of reconceptualization, since Metz’s work is not a continuation of the tradition based on Schmitt’s approach, and does not focus on the debate with Schmitt. However, it is also unrelated to thinkers who understand by the term political theology the historical intertwining of political and religious power (a state of affairs which essentially existed only in pre-modern eras). Metz’s interest is in exploring the crisis of religious faith, specifically within the Catholic Church. He saw that a still broader crisis, the crisis of European culture, underlay this, thus the new political theology could be explained in this context.

As early as the mid-1960s, Metz was emphasizing in his writings that Catholic theology did not take the aspirations of the Enlightenment, or their consequences, seriously enough. It was content to emphasize that romanticism could be interpreted as a ‘counter-Enlightenment’, and that, in consequence, to believe that idealist thinking adequately corrected the issues raised by the Enlightenment. This resulted in Catholic theology lagging behind its own age. For that reason, a critical confrontation with the Enlightenment on the terrain of Christian theology was necessary. In this critical discourse, theology must answer important practical questions (especially with regard to freedom), and at the same time emphasize that the church is, by its very nature, a public, political institution. Its message is to all people. This universality gives the church a special character as a political institution, namely that it must always look to society as a whole, and must never be identified with the (secular) political aims of a particular class, stratum, group, or party.

In Metz’s use, the term ‘political’ has nothing to do with party politics, and does not seek to fuse reason and faith. That is, he does not consider it possible for politics to be transformed into the certain consciousness of salvation. In his view, it is precisely this impossibility that justifies the need for political theology. Historical experience shows that what happens in the world of reason can be dangerous from the point of view of identity. The public visibility of faith-based political theology is of great significance in preventing this. For that reason, Catholic theology must be prepared to debate philosophers who argue on the basis of reason. It must not allow representatives of the enlightened mind to determine what is to be considered Christian. The essential nature of Christianity cannot be reduced to the results of an intellectual- historical examination.

Christian political theology rejects the optimistic Enlightenment belief in progress, for it seeks to remember those who have fallen out of collective memory, itself defined in the modern age by the myth of progress.

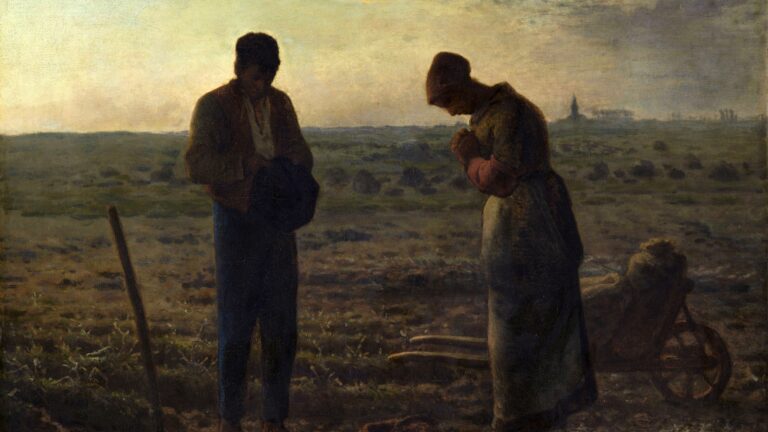

Remembrance is one of the most important concepts in Christianity. The Christian faith is a condition in which one remembers the divine promises, and the hopes that flow from them. Remembrance is not about idealizing the past, it is rather a call to rethink our relationship to the present, and is therefore pregnant with danger. Remembrance is the foundation of the public existence of Christianity. According to Metz, who connects faith to remembrance, Christian political theology should first and foremost remember and remind us of the history of the suffering of human beings, since mankind is characterized not primarily by sin but by suffering.11 Metz speaks in favour of limiting the Augustinian tradition within the history of theological thought. St Augustine argued that suffering in the world was due to the sin of mankind, and that since suffering is vast, so too must be the sin. As such, sin appears to be the defining characteristic of humanity. Metz, by contrast, expressed his conviction that Jesus, looking at mankind, saw not the sin but the suffering. As such, the starting point should not be the sin, but the suffering.

The question, then, is not how God punishes sinners, but how He provides restitution to those who suffer. The Christian faith remembers suffering in the context of the resurrection; that is, it is not because of progress made in time but because of the apocalypse that remembrance is indispensable, despite its subversive power in every present moment. This belief is enlivened by the faith that all are equal before God, and that those who have been erased from human history may receive ultimate justice.

Since the Enlightenment, we have witnessed a transformation in the range of meanings contained within the concept of politics

Since the Enlightenment, we have witnessed a transformation in the range of meanings contained within the concept of politics. On the one hand, we can see that a distinction has been made between state and society, in which the political no longer covers the state, and vice versa, the state cannot be resolved in a politicized society. On the other hand, the political order emerged as an order of freedom. In this new historical-political context, the primary task of political theology is one of de- mythologization; to reject the myth that religion is exclusively part of private life. Metz instead emphasizes that theology seeks to encompass the existence of the individual, and that social, public existence is part of that existence. In other words, religion cannot be reduced to the private aspects of human life. Metz argues, in contrast to both Marxism and liberalism, that religion is inherently political in nature. Its political essence includes the range of issues facing society as a whole, including the question of God.

Political theology is not a new subject area within theology, nor ‘applied’ (to public life and politics) theology, but nor is it political ethics or social theology. Instead, it is a critical perspective. Metz agrees with the idea expressed in Peterson’s analysis of monotheism, namely that the direct politicization of the Christian message has had a negative effect, and has ideologically distorted the faith content of Christian eschatology. However, this theologically unacceptable attempt did not in itself discredit the pursuit of Christian political theology. Metz explained both why Christian theology is ‘political’ and why it nevertheless cannot be translated directly to justify the exercise of worldly power. In the Christian conception of God there is a role for a category of a political nature and for power. However, the message of Jesus is clear: this power cannot be interpreted on the basis of existing power structures. Not least because theological conceptions of God’s rule emphasize the transcendence of this rule, and the consequent relativity of all secular rule. This is the source of religious criticisms of political arrangements that regard themselves as ‘absolute’. Theology regarding the rule of God takes as an a priori the necessity of freedom in this world. The church, as an institution, has a critical and a liberating role, maintaining the possibility of salvation for all people. Hope does not lie within the church, but within the Kingdom of God.

The new political theology, then, is a ‘world-oriented theology’. In other words, it is a vision that speaks of God from the context of its own time.12 According to Metz, the Enlightenment disrupted the harmony between religion and society, and in this situation we must insist that religion should not be limited to private life, but rather, as an accepted public actor, should be free to say what it has to say to the public, and society at large. The public, therefore, cannot remain closed off from it. On the contrary! It is the indispensable medium for preaching. That must be the case if we take freedom seriously. In striving towards the public, theology can once again become a political theology, that is, a ‘practical’ theology that is not interested in the intertwining of religion and power, but that links the interpretation of faith to the question of social action.

Both the ‘old’ (by which is meant the Schmitt approach) and the ‘new’ political theology saw themselves as diagnostic approaches on the terrain of modernity, and both assumed that politics was not a definable field of study or a set of demarcated goals, but rather the aggregated sum of interactions between groups and individuals in society. Furthermore, each professed the primacy of practice, with Schmitt focusing on the concept of the decision and Metz on the responsibility of the individual. However, there are also significant differences between the two. Schmitt looked expectantly for a sovereign in a state of exception, while Metz wanted to shape this new order into a place where religion could once again play a public role. Metz based his arguments on biblical monotheism, while for Schmitt’s political theology, monotheism was not a fundamental issue. Schmitt theologized politics, while Metz sought to make theology politics.13 According to Metz, Schmitt took as his starting point the universality of all-pervading sin, and this led to his doubts concerning democracy. Metz, on the other hand, saw that what defined the life of humankind was not sin but suffering.

Translated by Thomas Sneddon

NOTES

1 Carl Schmitt, Political Theology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

2 Ernst Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies. A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957). This can also be related to the approach taken in Jan Assmann, Herrschaft und Heil: Politische Theologie in Ägypten, Israel und Europa (Dominion and Salvation: Political Theology in Egypt, Israel, and Europe) (Munich: Carl Hanser Verlag, 2000). Erik Peterson Schmittel’s controversial book may also be placed in this circle: Erik Peterson,Monotheismus als politisches Problem (Monotheism as a Political Problem) (Leipzig: Jakob Hegner, 1935).

3 Max Weber, Economy and Society (Berkeley–Los Angeles–London: University of California Press, 1978). On Weber’s concept of charisma see Thomas E. Dow Jr, ‘The Theory of Charisma’, The Sociological Quarterly, 10/3 (1969), 306–318.

4 Schmitt, Political Theology, 36.

5 Tamás Nyirkos, ‘The Myth of the Secular State’, Hungarian Conservative, 3 (2021), 44–49.

6 Carl Schmitt, Römischer Katholizismus und politische Form (Roman Catholicism and Political Form) (Hellerau: Jakob Hegner, 1923).

7 Schmittel argued most convincingly in this regard. In his view, there are no theological moments in the modern conception of history. See Hans Blumenberg, Die Legitimität der Neuzeit (The Legitimacy of the Modern Age) (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 1966).

8 Schmitt, Political Theology, 15.

9 Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995); Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception. Homo Sacer II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

10 Agamben, State of Exception, 23.

11 Johann Baptist Metz, Memoria Passionis: Ein provozierendes Gedächtnis in pluralistischer Gesellschaft (Memoria Passionis: A Provocative Memory in a Pluralistic Society) (Freiburg: Herder Verlag, 2006).

12 Johann Baptist Metz, Zum Begriff der neuen Politischen Theologie 1967–1997 (On the Concept of the New Political Theology 1967–1997) (Mainz: Matthias Grünewald Verlag, 1997).

13 As for the comparison between old and new theology, see John K. Downey, Jürgen Manemann, and Steve T. Ostovich, eds, Missing God? Cultural Amnesia and Political Theology (Münster: Lit Verlag, 2006).