Last week, the European Commission unilaterally chose to bypass the EU’s principle of unanimity for the purpose of permanently freezing Russian assets.

While a blatant violation of the bloc’s founding treaties, it was hardly an unusual move. In fact, since even before the Brexit vote in 2016, the bloc has been trundling down the authoritarian path.

Hungary has faced the brunt of these attacks over the last decade. Despite being less economically developed than many Western countries due to the cruel legacy of Communism, Hungary has become a net contributor to the bloc this year due to being forced to hand over €1 million in fines to Brussels every single day over its decision not to let in limitless migrants.

Meanwhile, far wealthier countries in the West continue to act as parasites to the bloc. Looking at you, Belgium.

But the coercion goes beyond that. The bloc has repeatedly threatened Hungary for its positions against the Ukraine war, regularly withholding important developmental funds over Budapest’s refusal to adhere to Eurojingoism. Meanwhile, non-bloc countries in Africa and Asia receive hundreds of millions from EU coffers, despite offering little in return.

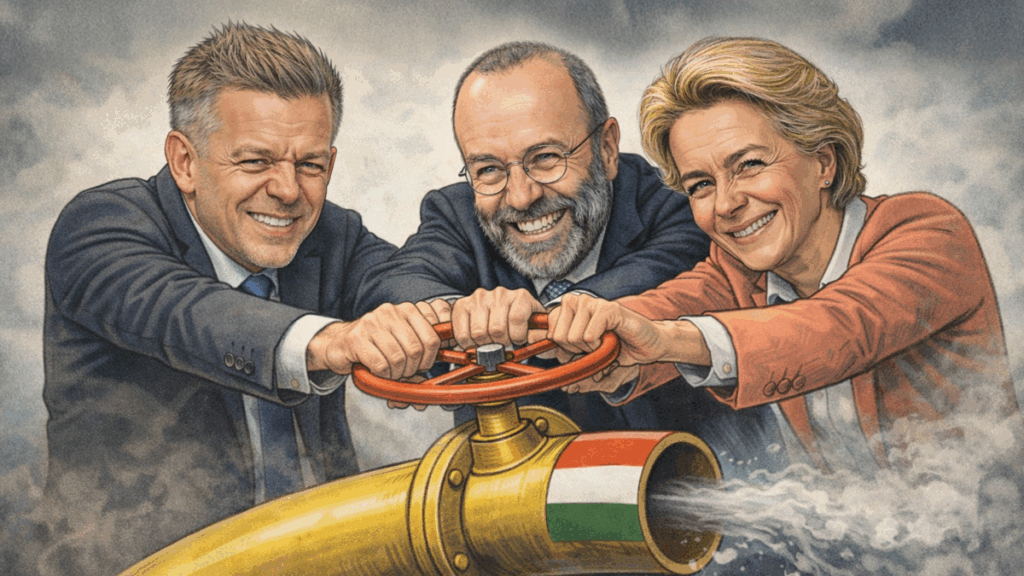

But Hungary is no longer the union’s only victim. Slovakia has become a greater target in recent months over its decision not to destroy its own energy system to serve the war in Ukraine, the move resulting in coordinated economic sabotage from Brussels and Kyiv.

Even former core countries, including economic basket-case Belgium, are now on the receiving end of political attacks, with Eurocrats warning the bloc will be ‘treated like Hungary’ over its refusal to take legal responsibility for seizing Russian assets in a desperate attempt to prop up Ukraine’s war machine.

Europeans have no way of effectively protesting the Commission’s actions. President Ursula von der Leyen is appointed by unpopular governments, no single one of which has the ability to reel her in, and the European Parliament is a bloated mess of yes-men that will be irremovable until at least the next bloc-wide elections in 2029. Even criticizing their power is becoming increasingly difficult with online censorship rules, such as the EU-wide Digital Services Act, as well as member state rules in France and Germany against ‘insulting’ certain politicians.

By contrast, nations like Hungary continue to practice democracy. The administration in Budapest faces an election this coming April, during which citizens will be able to decide whether or not they are satisfied that the Fidesz government truly represents them on the world stage. While polling is contentious, overall evidence points towards the party winning that vote.

But even if they do not, there is little fear that the ruling government will not hand over the keys of power peacefully to whatever other group Hungarian citizens could end up choosing. Unlike von der Leyen, they have not rigged the game in their favour. They do not jail opposition politicians (except, admittedly, when they attack someone with a hammer).

Related articles: