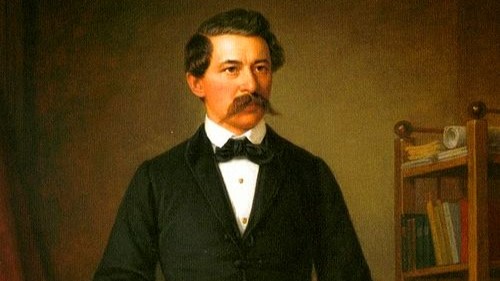

In the brutal and depressed aftermath of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, one poet was asked to craft a poem celebrating the Emperor Franz Joseph I on his first visit back in the subdued Hungarian territory. This poetical genius was none other than János Arany, whose statue stands proudly in the garden of the National Museum to this day.

Among the plethora of his great works, this piece is one that certainly etched him all the more firmly in the hearts of Hungarians. It is a masterwork that mirrored the Nation’s intense feeling of loss and deep grief.

When Arany received the royal request to write a celebratory poem, he could not bear to respond by following the wishes of the Austrian Emperor. He, therefore, devised a masterful coded response. His ingenious creation was published under the title: A walesi bárdok in Hungarian and has, since, also received quite a lot of renown in its English translated version as The Bards of Wales.

The piece is a remarkable 120 lines and 30 stanzas long. It consists of an alternating syllable count of 8-6-8-6. The piece has a unique English ballad feel while also conveying a deep Hungarian sensation. It is one of those poems which absolutely springs to life in the mind of the reader and does not take its leave after a rendition.

In short, the work symbolises the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and its outcome, a tragic loss. Symbolically, Emperor Franz Joseph I is portrayed as the English King, Edward I, who hosts a feast while visiting his newly conquered dominion of Wales.

‘This piece…is a masterwork that mirrored the Nation’s intense feeling of loss and deep grief’

At the time, local culture was suppressed via systematic attacks on Welsh laws, language, customs and history. The legend, as portrayed in Arany’s poem, is that the king held a large feast at the Castle of Montgomery, where he missed songs praising him and his great deeds. The Welsh at last rose to give him song. But, they only sang of the brutality and horror he committed against their people, thereby making their stand against the tyrant.

This prompted the ruler to have all of the Welsh bards who defied him, across the entire kingdom, be burned at the stake.

Arany connects the singing bards with the Hungarian people, who did not receive the Emperor kindly after the conflict. The burning at the stake symbolises all of the Hungarian patriots who died fighting in defiance of the oppressor. While the never-ceasing song is the nation’s, the people’s voice, which gets stuck in the king’s head.

Finally, the piece ends with his world burning with those at the stake and him hearing echoes of the bard’s song in complete silence, maddening him. A symbol of a guilty conscience due to vile acts against a people. Where at last the people prevail above him.

At the time, Arany’s poem made it through the Austrian press censorship since it could be played off as it being just a Welsh tale with no relation to Hungary. The current events were not emphasised in a direct and obvious way. Yet, the call of strength and defiance was understood by the Hungarians and resonated deeply. The work has become a deeply embedded part of the Hungarian conscience, on the lips of hundreds of school children every year, as required learning material nationwide. Today, there is practically no Hungarian who has not heard of the bards of Wales.

It is also of note that the work has strengthened the connection between the nations of Hungary and Wales. Since the poem’s translation, it has become known and celebrated in Wales as a unique foreign rendition of their history. It is remarkable how it works both ways, as a Hungarian allegory and as a more literal telling of Welsh events, resonating deeply with both peoples.

To top it all off, in 2017, János Arany was made an honorary citizen of the Welsh town of Montgomery. Later, in 2022, the poet even received a memorial plaque in the town, whereafter a ceremony celebrating the cultures of Hungary and Wales was held.

Today, Arany’s legacy lives on nationally and internationally as someone who spoke for a nation in a moment of deep peril and despair. His poem and attitude form a strong pillar of Hungarian national identity and continues to be recited as a symbol of defiance and a reminder of past heroes.

Related articles: